Painting into Poetry: The Case of Derek Mahon

Rajeev S. Patke

National University of Singapore

“With respect to Daumier: you are quite

right in suggesting that he paints his own mirror image when he paints

Quixote.”

(Benjamin to Adorno, 23 February 1939)

Art that depends on another art begs the

question of why there is more enterprise in being derivative. This essay describes

the relation between poetry and painting in terms of an artist’s

need for imaginative space as the productive outcome of a tension between temperament and

circumstance, treating Derek Mahon’s poems on paintings as a specific instance of a general type of literary allusion in

which “firstness” is made to give over to “secondariness.” I

will argue that belatedness–as of the forger selling fake Vermeers to Goering in Mahon’s poem of

that name–brings forth “a light to transform the world”1 through the

melancholic knowledge it elicits from the blind sightedness of “the

first”. In such art, Peirce’s

notion of redness in itself–whatever that might mean–is

transformed to the red in our eye, as we look in troubled wonder at what such

reflections betoken.2

By temperament I mean the individual disposition that makes habitual

recourse to art a primary mode of experience rather than interpretation, as when Elizabeth Bishop describes poetry not as a matter of interpreting the world

“but the very process of sensing it” (34).3 To such a temper, an allusion to

art is not a refractory lens, but a mode of conversation, as when the

wood which knows itself to be the medium in Mahon’s “The Drawing Board” speaks

of the artist making sense because he is “Talking to me, not through me” (CP

125). In the case of Mahon, temperament refers specifically to

the posture of involved dissociation that has been read as his characteristic attitude to

matters Irish, which takes determined recourse to

European art regardless of how this provides an analogy to the relation of W.B.

Yeats to Romanticism, or Aimé Césaire

to Surrealism.4 To a temperament that Patrick Kavanagh, and Seamus Heaney after him, have called

“cosmopolitan,” elective affinities are indistinguishable from the decolonizing

resistance which holds at bay various notions foisted on the Irish writer of what might be

deemed subjects apt or appropriate by a provincial notion of time and place.5

By circumstance I mean the resistance offered by experience to the medium

as its instigation, which, in the case of Mahon’s relation to Ireland and Ulster, becomes the

twisted loop of affiliation and disaffection walked by the poets described in

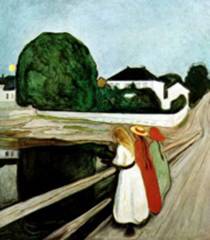

Seamus Heaney’s “Place as Displacement” (1984),6 and imaged, more broadly, in Mahon’s

“Girls on the Bridge”, as the mile of road where Munch’s teenagers–“Grave daughters / Of time” and

“Fair sisters of the evening star”–meet the “punctual increment” of their

lives in a scream (CP 152-53).

Poems whose coming into being depends in part on the prior

existence of an accessible imaginative space evoked or invoked through a

painting are contingent and continually repeated attempts to crystallize and

shatter this tension. Wallace Stevens once asked, rhetorically, “Does

not the saying of Picasso that a picture is a horde of destructions also say

that a poem is a horde of destructions?”7 In kindred mood, Mahon’s poems are horde and

hoard: they partly destroy the art they cherish, they partly cherish the destruction

that survives the cherishing, rendering art into the form for a final knowledge that will always be

incomplete and timely when late: “A sort of winged sandwich board / El-Grecoed to receive the word” (“Sunday Morning”, CP

126). As in the intertextual relation between contemporary

and baroque art analyzed by Mieke Bal, such

“quotations” acknowledge allegiance or debt to a predecessor’s work by inserting it into a

context that alters–and ironicizes–its ostensible

significance, reversing “the passivity implied in that perspective.”8

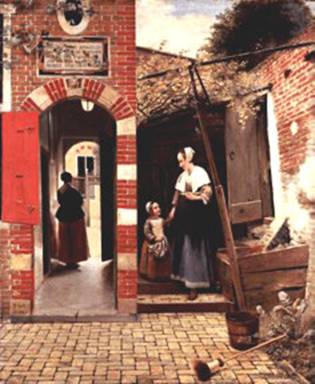

[Fig. 1 Pieter de Hooch, “The Courtyard of a House in Delft,” National

Gallery, London]

Consider the partial divergence in response

evinced by Mahon’s “Courtyards in Delft,” which

leaves his relation to the world evoked by Pieter de Hooch (1629-84)

thoroughly ambivalent. For Hugh

Haughton, who prefers to include the original–now elided–final stanza into his

reading, Mahon “recreates the ‘trim composure’ of a seventeenth-century Dutch

painting and translates its protestant urban idyll to the Belfast of his own

childhood-setting both against the ‘esurient seas’ that will one day breach the

‘ruined dykes’ and a vision of future violence which will discompose the ‘trim

composure’ of his own and the Painter’s art (and home).”9 We note

that the painter incorporated a textual quotation of a very literal kind into the

tablet engraved above his representation of the archway, which reads in Dutch:

“This is the Saint Jerome’s vale, if you wish to retire to patience and meekness. For we must descend if we

wish to be raised. 1614.”10

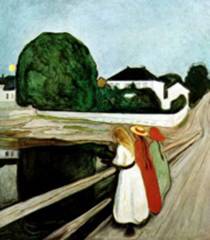

[Fig. 2 Detail from Pieter de Hooch,

“Courtyards in Delft,” National Gallery, London]

Thus Mahon is in iterative company from

the beginning. His secondariness

is preceded by a derivativeness intrinsic to the

motto, which is quoted from yet another quotation,

reminding us of Walter Benjamin’s notion of origin as no more than “an eddy in the

stream of becoming.”11 If we

take the painter to imply even a partial endorsement of his “origin,” then the poem–with or without its original final

stanza–cannot be read as a simple endorsement of what the painter seems to

contemplate in lovingly detailed celebration. Edna Longley, for instance, is

much less willing than Haughton to read the allusion to Delft as referring to an idyll.

Pointing to Mahon’s interview from Poetry Ireland

Review (1985)–in which he remarked that “I may have been trying to put back

in some of the karma that bad Protestants over the generations have

removed”12–she “identifies the suburban home, rather than the Paisleyite pulpit, as the heart of darkness, paralysis or

lost karma” (1995: 289).13

Curiously enough, the idea of a karma that can be lost is alien to the

Hindu ethos, in which it is figured more like the God of Francis Thompson’s

“Hound of Heaven,” relentless and irrefragable, less like the God who is “alive

and lives under a stone” in Mahon’s “The Mute Phenomena” (CP 82), than the

Christ who is supposed to have spoken of hunting the hunter in the stag’s

encounter with Placidus, an incident

commemorated in Mahon’s “St. Eustace” (as poem that is now exiled from the Collected Poems).14

Regardless, or therefore, the act of conjuration practiced in such poetry is an

attempt to dispel–not the significances evoked through, as well as by, a

painting, but–the anxieties confessed by and in the poem to the painting. The poet

talks to the painting: we simply overhear. In that sense, the poem depends on the

painting, not as a pretext, but as the silently initiatory presence in a conversation across

time. It dissembles itself as

marginalia, but only in order to over- or under-whelm the painting from this vantage point of marginal

vision. It is willing to occupy an

adjacency apparently twice-removed from experience, folded over itself between

allusion and divagation, as between estrangement and attachment. Such poems treat the space of the painting as

a liminality to be crossed by, or in, the poem into

an alterity which may be recognized as what

Michel Foucault meant by the notion of heterotopia,15 and Paul Muldoon has treated, more recently,

through Beckett’s allusion to a narthex.16 I shall first refract Mahon’s poems through

the Foucaldian notion, and then explore the

suggestive power and applicability of Muldoon’s narthex in respect of Mahon.

Foucault’s notion focuses on sites which contradict the

connections they establish. It dissuades

us from treating mimeticism as if a picture were a mirror or a

window, even if the model in Sir John Lavery’s “Daylight Raid from My Studio

Window,” which graces the front cover of Mahon’s Collected Poems (1999), is arranged in

such a way as to have us looking at her back as she looks

out the large bay window.

[Fig. 3 Sir John Lavery, “Daylight Raid from My Studio

Window,” Ulster Museum, Belfast]

The metaphor of the figure makes us participate, instead, in

what Foucault called a “mixed, joint experience” (266). Mahon constructs for yet another such figure, the

girl standing with her back to us in “Courtyards in Delft,” a narrative of waiting of

the kind also inscribed for and in the poem by the figures on Keats’s urn. Mahon’s poem

speaks of the “chaste perfection of the thing and the thing made” (CP 105). One way of reading the distinction would be

to take the “the thing” as the world and “the thing made” as the painting. But the poem permits another sense to supervene, so that “the

thing made” could refer to the painting as

the world-in-representation, and “the thing” would then point to the materials or medium–the

“cracked paint”–from which the world-as-representation is made. In Aristotelian terms (e.g. Physics, Book 2, Chapter 3), this would be

the material cause underlying percept-as-concept. Of

course, if we turn to the poem, then a third sense opens out, in which the

painting becomes “the thing” and the conversation created by

the poem with that painting becomes “the thing made.” In any case, the alternative senses do

not contradict one another; they confirm the double-jointed nature of both painting and

poem as occupying a notional space that we could recognize as heterotopia. Foucault describes this as “a mythic and real

contestation of the space in which we live” (266). Likewise, we could say that if “The mild herbaceous air / Is lemon-blue” in Paulo Uccello’s

“Hunt by Night,” the color invokes a perspectival space beyond – not simply behind–the

receding horizon alluded to by the painting.17

[Fig. 4 Paulo Uccello,

“The Hunt,” Ashmolean Museum, Oxford]

Foucault claims that “heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a

single real place several spaces, several sites, that are in themselves,

incompatible” (268). The recognition of such a co-existence of divergent possibilities

is the knowledge discovered by the poet in the conversation of poem with

painting.

Foucault characterizes heteretopic space as beginning “to

function at full capacity when men arrive at a sort of absolute break with

their traditional time” (269). He

illustrates the spatial embodiment of a break in time through several lists. First there is

boarding-school, honeymoon hotel, rest home, psychiatric hospital, cemetery, barrack and

prison. Then there is theatre,

cinema, garden, and rug. And then there is museum,

library, archive, festival and fairground.

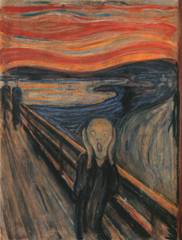

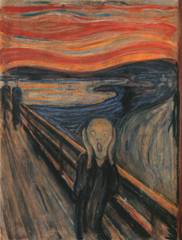

To this we can add poems that make sustained allusions to

paintings. They function like the two

bridges in Mahon’s poem “Girls on the Bridge:” the first bridge is that of the

allusion to at least one of several paintings by Munch on the theme of “Girls on a Bridge” (c1900-1901), and the

second bridge links the allusion from one picture to another Munch painting,

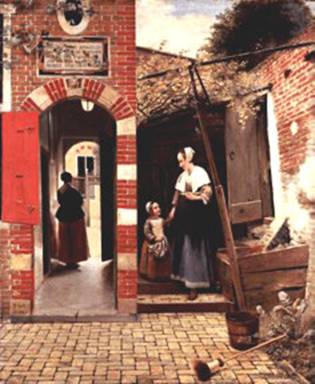

“The Scream” (c.1893-94).

[Fig. 5 Edvard

Munch, “Girls on a Bridge,” National Gallery, Oslo]

That “The Scream” should have preceded “Girls on a Bridge” by about seven years in Munch’s oeuvre illustrates how the break in time that Mahon

(and Foucault) might have in mind is not be seen in simple linear terms.

[Fig. 6 Edvard

Munch, “The Scream,” Munch Museum, Oslo]

The break, as Mahon’s poem may

be said to labour the point, is also a jointure, and

what it connects is two distinct fragments of knowledge, each true in its own

time-space (Bakhtin would have said, chronotope), more poignant for being held together in forced stereoscopic

disjuncture. The reason that could be

said to address or redress this disjuncture, leads Foucault to the final

function he attributes to heterotopia: purification. Heterotopic space either “exposes every real space … as

still more illusory”, or “it can create another space, “as well

arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed and jumbled” (271). If Mahon’s “Girls on

a Bridge” exposes the mutuality between the two Munch paintings as an either-or that impels

them towards collision, another variety of allusive poem illustrates the function of heterotopia as purification through

compensation.

The objects alluded to in Mahon’s poems on

paintings reveal an impetus toward two kinds of imaginative displacement in

time: one proleptic, the other analeptic. In the first variation, the forward movement,

as in “Courtyards in Delft” or “Girls on the Bridge,” fears a time that overshadows the

apparently untroubled present reflected in the paintings. The present of one representation is treated

by the other as a form of calmness or innocence unmindful of how the sky

darkens around its spaces. It is as if the

poem saw itself as a gloomy future lying in wait for a semblance of quietness

that is belied by a turbulent truth always already in waiting. This is exemplified in “Schopenhauer’s Day”, the fifth

section of “The Yellow Book” (CP 232-33).

The poem has moments when it might be echoing–or quizzing–sentiments

familiar to us from someone like Adorno:

The only

solution lies in art for its own sake,

redemption through the aesthetic…

But the poet’s habitual recourse to art is treated with

self-reflexive irony:

Bring out the

poets and artists; take

music, the panaceas for all our woes…

or the calm light of Dutch interior art…

And then deflated by the anxiety that we might have

bequeathed some frightfulness to a future time:

‘Through the cortex

a great melancholy blows

as if I’d seen the future in a dream–

…

and the angel of history, a receding ‘plane

that leaves the cities a rubble of ash and bone… (CP 233)

Mahon thus

revives Benjamin’s melancholic reading of Klee’s

receding angel of history as a despairing prophecy or intimation of doom. That might be said to serve a purificatory function in relation to a future that promises

regression, and in a time which finds hell more compelling for the imagination

than the “luminous geometry” provided by Botticelli

for Dante’s vision of paradise,18 which the

now omitted antepenultimate stanza of “The Sea in Winter” alludes to as

Diagrams of

that paradise

Each has his

vision of.19

[Fig. 7 Sandro

Botticelli’s illustration for Dante’s Divine Comedy (Paradiso,

06)]

But it would appear that poems which imagine painters imaging heaven

have not fared well in the poet’s canon.

Gone is the Van Gogh who claimed that he had to go South

And paint what

I have seen–

A meteor of

golden light

On chairs,

faces and old boots…20

The poems that have survived are more prone to a backward

movement that would negate, dissolve, or savage history. Their need for conversations with art feeds

on the desire to revert to a time before origin:

and start

again on the fresh

first

morning of the world. (CP 279)

This tendency is exemplified in the relatively early poem, “The

Studio”, which alludes to Munch, and also in a more

recent poem, “‘Shapes and Shadows’,” which evokes the abstract expressionism of

a William Scott still life from the Ulster Museum. In either poem, the domestic

objects that are the metonymies of ordinary existence are read off from the

paintings as fraught with an energy that is driven to breaking free of form, shape and substance,

in order to return matter and color to a state prior to, and in preparation for, renewed

existence. So behind all the pots and

pans,

behind

these there loom

shades of

the prehistoric,

ghosts of colour and form,

furniture,

function, body … (CP 278)

[Fig. 8 Robert Scott, “Still

Life,” Ulster Museum, Belfast]

The energy in such poems could be said to approximate to what Foucault

describes as the purificatory function of heterotopia. It is also close to what Simone Weil meant by

“decreation:”

Simone Weil in La Pesanteur et La Grâce has a chapter on what she calls decreation. She says

that decreation is making pass from the created to

the uncreated, but that destruction is making pass from the created to

nothingness. Modern reality is a

reality of decreation.21

Turning from the conjuring power of heterotopic spaces to the more

specifically Irish connotations of Muldoon’s idea of a narthex, we first note

how the idea gets translated from its use by Beckett

The speaker of The Unnamable …

wonders, “Are there other places set aside for us and this one where I am, with

Malone, merely their narthex?”22

In the Beckett text, the “is” of “where I am” implies a

tension between one’s place in time and space on the one hand, and desire or

justness or ideality as an “ought to be somewhere else” on the other. One could say that those such as Malone–or

Mahon–bespeak a sense of doubleness in which

existence is a narthex to an other space whose shadow

we call existence. However, Muldoon takes the

idea in a slightly different direction:

A “narthex,” I remind myself, is “properly the name of a

tall, umbeliferous plant with a hollow stalk”–a

“stem,” you might say–“also, a small case or casket for unguents.” The primary definition, though, is “a

vestibule or portico stretching across the western end of some early

Christian churches and basilicas, divided from the nave by a wall, screen or

railing, and set apart for the use of women, catechumens, penitents and other persons; an

ante-nave.” (17-18)

Muldoon develops the notion of the narthex as a metaphor central

to the characteristic preoccupations of Irish writing, that is, of a tradition

which Heaney has described as always “balanced between destiny and dread.”23 In

Muldoon’s fascinating characterization, the

narthex becomes a mind-set exhibited repeatedly, and almost habitually, by

Irish writers. In their hand,

as he demonstrates ingeniously, the narthex develops a whole host of

conventions. One of them involves a

journey and an encounter for which we can

find analogues in Mahon:

This idea of there being a contiguous world, a world coterminal with out own, into and out of

which some may move, as in Allingham’s “The fairies,”

might be traced back to the overthrow of the Tuatha Dé Danann by the Milesians, for after the battle of Tailtiu and Druim Ligen, the Tuatha Dé Danann are literally driven underground. They become

the áes sídhe, the

“fairy” or “gentle” folk… In the Fenian cycle of

tales, the confrontation with, and crossing over into, a fairy

realm often takes place during a hunt with hounds, sometimes to the ringing of

bells … or the strains of an unearthly music, or ceol sídhe, and it usually involves some kind

of time warp. This idea of a parallel

universe, a grounded groundedlessness, also

offers an escape clause, a kind of psychological trapdoor, to a

people from under whose feet the rug is constantly being pulled, often quite literally so. (7)

Mahon’s poem “St.

Eustace” provides just such an encounter with “gentle”

folk. He dramatizes the legend of the

Roman Placidus, and his conversion through a

vision of a crucified Christ on the antlers of the deer he had been

hunting, through Pisanello’s imaginative rendition of

this mythical encounter (National Gallery, London). As James Fenton has

demonstrated, Pisanello occupies a peculiar role in

the art historians’ narrative of Renaissance Humanism. What has survived of his

art is remarkable for its precise and careful attention to detail in his

representations of the animal world: a feature that older art historians

such as Berenson and Huizinga

were inclined to treat as evidence of an insufficient focus on the

human. Yet it is precisely that–as

Fenton remarks, and as Mahon demonstrates–which we are now more likely to cherish. There is also a degree

of stylization to his art that Mahon refracts

and Fenton describes with great insight:

The savage splendour, the “barbarity”

of the northern courts evoked by Huizinga, the world

of chivalry, of jousts and tournaments and heraldry, of war

deemed beautiful, the world of Arthurian fantasy shaping actual bloody

events–this, too, is Pisanello’s world.24

[Fig. 9 Antonio Pisanello,

“St. Eustace,” National Gallery, London]

Mahon’s Placidus could be said to have entered a narthex in

which his culture of ritual violence is suddenly brought up short against the

power of a very different kind of exhortation.

He will not burn,

Now, with such nonchalance

Agape beasts to

the gods of Rome

Whose strident,

bronze imperium

He served devoutly once

But in his turn25

The beast with mouth agape killed in ritual slaughter is punningly twinned with its heterotopic opposite, the beast keeling

before the hunter, full of love as agape. Likewise, the “turn” from Roman to Christian is

accompanied, at the end of the incomplete grammar of the stanza quoted above,

by the anticipation of a grisly reversal, in which, as

the narrative of St. Eustace goes, the Roman convert ended up being

braised in a “charcoal brazier” as the specific “turn” of his martyrdom. No surprise to discover Muldoon saying:

“The féth fíada also

usually has the appearance of a wild animal, a deer…” (75). As in the “Hunt by

Night,” violence is not averted or avoided in the narthex, but its import allows contrary

elements to meet or meld. In the Uccello painting, what Mahon fixes his

gaze upon is “The ancient fears mutated / To play…” (CP 150). The poem

balances the opposition between “great adventure” and “elaborate

spectacle.” The tensions held suspended

in “St. Eustace” cut more sharply. The

phenomenon finds its apt description in Muldoon:

This tendency towards the amalgam, the tendency for one event or

character to blur and bleed into another, what I’ve called

elsewhere an “imarrhage,” is a staple of Finnegans Wake. (74)

“Imarrhage” is also a staple of Mahon’s tempering art. As with Pisanello,

the mildness and the “contumacy” are held unblinkingly, like grit, in the

eye. In such a poem, the painting is not

ironicized, it enables Mahon to use

opposed forces–Christian love and Roman contumacy–to ironicize

each other. In this overheard conversation, the poet

does not speak to the painting, he hustles it into disclosure. That which had

been held latent in the silence of the visual medium is pushed from its veiled

translucence to a more pungent and acrid declaration. One might repeat with Muldoon that Mahon (and

each painter that he converses with) is “therefore hard-wired, as it were, to

simultaneously embody both attachment and estrangement” (123).

Notes

1. Derek Mahon, “The Forger,” in Collected Poems (Loughcrew,

Old Castle: The Gallery Press, 1999), 24. This

book is hereafter referred to parenthetically in the text as CP.

2. For “firtsness,” see C. S. Peirce,

“The Reality of Firstness,” Harvard Lectures on Pragmatism (1903), “Lecture IV: The Seven

Systems of Metaphysics,” in The Essential

Pierce, edited by The Peirce

Edition Project, vol. 2 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998),

188, and “What Pragmatism Is,” (1905), 331-45. Cf. Collected Papers, vol. 5 (1993), 66-81.

3. Elizabeth

Bishop, quoted in The Voice of the Poet:

Elizabeth Bishop (Random House Audio Books). New York: Random

House, n.d., 34.

4. Declan Kiberd, “From Nationalism to Liberation”, in Representing

Ireland: Gender, Class, Nationality, edited by Susan Shaw Sailer (Gainesville: University Press of

Florida, 1997), 21.

5. For example, Robert F. Garratt, Modern Irish Poetry: Tradition and

Continuity from Yeats to Heaney (University of California

Press, 1986): “The expatriated or outside perspective…reserve, reticence, an

uneasy cosmopolitanism … dissociation… a final inability of the imagination to

take root (263); “ … posture of exile” (265); “A

frequent version of this isolation comes in the image of a poet at his

window…” (272); “The poetic quest has become Mahon’s hunt by

night” (273).

6. Seamus Heaney, Place and Displacement: Reflections on

Some Recent Poetry from Northern Ireland (first Peter Laver Memorial Lecture at Grasmere, 2nd August 1984. Trustees of Dove Cottage, 1984), 5-6: “When Derek Mahon, Michael

Longley, James Simmons and myself were having our first

books published, Paisley was already in full sectarian cry and, indeed, Northern Ireland's cabinet

ministers regularly massaged the atavisms and bigotries of Orangemen on

the Twelfth of July. . . . it seemed that conditions had to be outstripped and

it is probably true to say that the idea of poetry was itself that higher ideal to which the

poets unconsciously had turned in order to survive in the

demeaning conditions, demeaned by resentment in the case of the Nationalist, by

embarrassment at least and guilt at best in the case of the Unionists.” Heaney’s notion of

Mahon’s “bi-location” may be compared with a more recent delineation of exile

and being-on-the borders from Walter Mignolo, in L. Elena Delgado and

Rolando J. Romero, “Local Histories and Global Designs: An Interview with Walter Mignolo,” Discourse

22:3 (Fall 2000): 16: “To be in exile is to be simultaneously in two locations

and in a subaltern position. And those are the basic conditions for border thinking to emerge at different levels:

epistemic, political and ethic.”

7. Wallace Stevens,

“The Relations between Poetry and Painting,” Stevens: Collected Poetry and Prose, selected by Frank Kermode and Joan Richardson (New

York: The Library of America, 1997), 741.

8. Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art,

Preposterous History (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago

Press, 1999), 8-9.

9. Hugh Haughton,

“‘Even now there are places where a thought might grow’: Place and Displacement in the Poetry of

Derek Mahon,” in The Chosen

Ground: Essays on the Contemporary Poetry of Northern Ireland, edited by Neil Corcoran (Bridgend: Seren Books, 1992), 104.

10. Walter Liedtke, Vermeer and the Delft School (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001), 282.

11. Walter Benjamin, The

Origin of German Tragic Drama, translated by

John Osborne (London and New York: Verso, 1977), 45.

12. Derek Mahon, Poetry Ireland Review 14 (Autumn 1985): 14.

13. Edna Longley, “Derek Mahon: Extreme

Religion of Art,” in Poetry in

Contemporary Irish Literature, edited by Michael Kenneally (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 1995), 289.

14. Derek Mahon, Selected Poems (Oxford: Oxford University Press, New

York: Viking, 1991), 144.

15. Foucault,

Michel. In Politics-Poetics

documenta X – the book. Edited by Catherine David et al, 262-272. Ostfildern: Cantz,

1997. All subsequent parenthetical page references refer to this source.

16. Paul Muldoon, To Ireland, I (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

17. Ironically, it

has been observed of the Ashmolean Museum painting:

“The ‘nocturnal’ or ‘moonlight’ tonality is due in great part to the tonal

change sin the pigments, above all the greens, browns and blues which have

grown darker, while the yellows and reds are well preserved,” in Franco and

Stefano Borsi, Paolo

Uccello (London: Thames and Hudson, 1994), 342c.

18. For images of

the Botticelli illustrations, see the Columbia University Digital Dante

web site at <http://dante.ilt.columbia.edu/images/index.html>

and Sandro Botticelli: The Picture Cycle for Dante’s

Divine Comedy, Hein-Th. Schulze Altcappenberg, et al. (New York: Harry N.

Abrams), 2000.

19. Derek Mahon, Poems 1962-1978 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979),

114.

20. Mahon, Poems 1962-1978, 14.

21. Wallace Stevens,

The Necessary Angel: Essays on Reality and the

Imagination (New York, Vintage Books, 1965), 174-175.

22. Quoted Muldoon,

17, from Samuel Beckett’s Trilogy

(New York: Grove Press, 1955), 293.

23. Seamus Heaney, “Mycenae Lookout,” The Spirit Level (London: Faber & New York:

The Noonday Press, Farrar Straus Giroux, 1996), 35.

24. James Fenton, “Pisanello: The Best of Both Worlds,” in Leonardo’s Nephew: Essays on Art and Artists

(New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998), 46.

25. Mahon, Selected Poems (1991), 144.

Works Cited

Bal, Mieke. Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History.

Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Beckett, Samuel. Trilogy. New York: Grove

Press, 1955.

Benjamin, Walter. The Origin of German Tragic Drama, translated by John Osborne.

London and New York: Verso, 1977.

Bishop, Elizabeth. The Voice of the Poet: Elizabeth Bishop. Random House Audio Books. New York: Random

House, n.d.

Borsi, Franco and Stefano. Paolo Uccello. London: Thames and Hudson, 1994.

The Digital Dante web site at

<http://dante.ilt.columbia.edu/images/index.html>.

Fenton James, “Pisanello: The Best of

Both Worlds,” in Leonardo’s Nephew:

Essays on Art and Artists, 41-49. New York: Farrar,

Straus and Giroux, 1998.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces.” In Politics-Poetics documenta

X – the book. Edited by Catherine David et al, 262-272. Ostfildern: Cantz,

1997. Originally published in Diacritics

16: 1 (Spring 1986): 22-27.

Garratt, Robert F. Modern Irish Poetry: Tradition and

Continuity from Yeats to Heaney. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Haughton, Hugh. “‘Even

now there are places where a thought might grow’: Place and Displacement in the Poetry of

Derek Mahon.” The Chosen Ground: Essays on the

Contemporary Poetry of Northern Ireland. Edited

by Neil Corcoran, 87-120.

Bridgend: Seren Books, 1992.

Heaney, Seamus. Place and Displacement: Reflections on Some

Recent Poetry from Northern Ireland. First Peter Laver Memorial Lecture

at Grasmere, 2nd August 1984. Trustees of Dove Cottage, 1984.

Heaney, Seamus. The Spirit Level .

London: Faber & New York: The Noonday Press, Farrar Straus Giroux, 1996.

Kiberd, Declan. “From Nationalism to Liberation.” In Representing Ireland: Gender, Class, Nationality, edited by Susan

Shaw Sailer. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997.

Liedtke, Walter. Vermeer and the Delft School.

New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001.

Longley, Edna. “Derek Mahon: Extreme

Religion of Art.” In Poetry in Contemporary Irish Literature.

Edited by Michael Kenneally,

280-303. Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 1995.

Mahon, Derek. Collected Poems. Loughcrew, Old

Castle: The Gallery Press, 1999.

Mahon, Derek. Poems 1962-1978. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1979.

Mahon, Derek. Selected Poems. Oxford: Oxford University Press; New

York: Viking, 1991.

Muldoon, Paul. To Ireland, I. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2000.

Peirce, C. S. Collected Papers, vol. 5. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Peirce, C. S. The

Essential Pierce, edited by the Peirce

Edition Project, vol. 2. Bloomington:

Indiana University Press, 1998.

Schulze Altcappenberg, Hein-Th.,

et al. (eds) Sandro Botticelli: The Picture Cycle for Dante’s Divine Comedy. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000.

Stevens, Wallace. Stevens: Collected Poetry and Prose. Selected by Frank Kermode and Joan Richardson. New York: The Library of America, 1997.

Stevens, Wallace. The Necessary Angel: Essays on Reality and

the Imagination. New York: Vintage

Books, [1951] 1965.

List of Images and their Sources

(All web site addresses given below were accessed on 1

July 2002)

Figs. 1 and 2

Pieter de Hooch,

“Courtyards in Delft,” National Gallery, London

[Source: <http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/cgi-bin/WebObjects.dll/CollectionPublisher.woa/wa/work?workNumber=NG835>]

Fig. 3 Sir John Lavery, “Daylight Raid from My Studio

Window,” Ulster Museum, Belfast]

[Source: scanned image from the cover page of Derek Mahon’s Collected Poems (1999)]

Fig. 4 Paulo Uccello, “The Hunt,” Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

[Source: Web Gallery of Art, at <http://gallery.euroweb.hu/html/u/uccello/6various/index.html>]

Fig. 5 Edvard Munch, “Girls on a

Bridge,” National Gallery, Oslo

[Source: <http://www.museumsnett.no/nasjonalgalleriet/munch/eng/index.html>]

[or The Poet Speaks of Art, at

<http://www.emory.edu/ENGLISH/Paintings&Poems/girls.html>]

Fig. 6 Edvard Munch, “The Scream,”

Munch Museum, Oslo

[Source: <http://www.museumsnett.no/munchmuseet/english/artworks.htm>]

[or

<http://www.museumsnett.no/nasjonalgalleriet/munch/eng/index.html>]

Fig. 7 Sandro Botticelli’s

illustration for Dante’s Divine Comedy

(Paradiso, 06: Mercury and Justinian)

[Source: <http://dante.ilt.columbia.edu/images/bott/par.html>]

Fig. 8 Robert Scott, “Still Life,” Ulster Museum, Belfast

[Source: <http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/irish/look/ulster/images/scott_stilllife.jpg>]

Fig. 9 Antonio

Pisanello, “St. Eustace,” National Gallery, London

[Source: < http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/future/pisanello.htm>]