Yeats among

Painters

(Yeats Summer School lecture, August 2006)

Rajeev S. Patke

I Introductory

‘I am a poet, not a painter’, Yeats declared in A Vision (1990: 134), but he was the

kind of poet who could affirm that ‘if we are painters, we shall express

personal emotion through ideal form, a symbolism handled by the generations, a

mask from whose eyes the disembodied looks, a style that remembers many masters

that it may escape contemporary suggestion’ (1961: 243). It should come as no

surprise, therefore, that the idea of Yeats among painters touches upon every

conceivable way in which a poet might find a use for painting while remaining securely

a poet. A person might write as well as paint; live among painters; express

decided views on individual works or on the arts in general; assimilate the

verbal and the pictorial into a general theory of culture and society; and write

poems that evoke specific pictures, either marginally, or centrally. At one

time or another, Yeats engaged in each of these activities. The result was a

life and a body of writing with an exceptional degree of integration between

the pursuit of poetry and a fascination with the plastic arts. I propose to

speak of this integration in a broad survey that begins with the poet in the

context of his family and affinities, then touches upon his views on the

painters he admired most, and then turns to the role played by paintings in

specific poems. Given the scale and diversity of the matter at hand, I shall

have to omit reference to the plays, the longer poems, and will touch upon his

interest in sculpture only very briefly.

The visual appealed to Yeats primarily for its symbolic

potential. In early youth he might have subsidized the idea that the painterly

and the poetical were intertwined, as in a poem which declares that ‘a song

should be / A painted and be [-] pictured argosy’ (Ellmann 1949:30). But Yeats

soon became weary and wary of poetry that was mimetic of painting. In 1888, he

wrote to Katherine Tynan, ‘We both of us need to substitute more and more the

landscapes of nature for the landscapes of Art’ (1997: 119). In 1913, he

declared he had long since rejected poetry based on ‘detailed description’ and

‘Impressions that needed so elaborate a record’ (1961: 348). In the late 1930s,

Dorothy Wellesley even suggested, somewhat reductively, that poor eyesight and

Celtic temperament combined to give Yeats an aversion to making poetry out of

the kind of visual detail that is generally included in the idea of Nature (1940:

190-1).

Be that as it may, Yeats was not drawn to the practice of

attempting in words what the painter does through line, colour, and design. For

him, the aesthetic moment presented a union of passionate thought and feeling in

the image. The nature of the image as he conceived it subsidized a fundamental

analogy between poetry and painting: ‘I began my own life as an art student and

I am a painter’s son, so it is natural to me to see such analogies’, he said (Loizeaux

1, in O’Driscoll 26-7). The most powerful source of symbolic imagery was the Anima Mundi, which he described as ‘a

great pool or garden’ in which the mental images of individuals have their

collective and interrelated being (1959: 352), such that ‘all those elaborate

images that drift in moments of inspiration or evocation before the mind’s eye’

‘are but, as it were, a condensation of the vehicle of Anima Mundi, and give substance to its images in the faint

materialisation of our thought’ (1959: 350).

II Family

Yeats attended arts school in his youth before deciding to give up art as a career in early 1886.

[2]

He continued to paint, now and then,

for more than a decade after that,

and was especially fond of his pastel of

[3]

Yeats’s

interactions with painting continued outside art school, in his father’s

studio, and through contact with the circle of friends associated with his

father. John Yeats had given up law for painting by the time his eldest son was

a schoolboy. The siblings had some training in art; the sisters later worked in

professions that were based in part on the arts and crafts. Lily embroidered,

Lolly taught art and worked at a printing press, and Jack won recognition as one

of

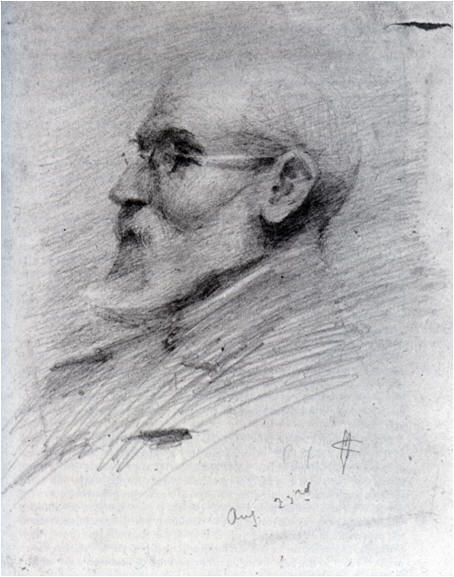

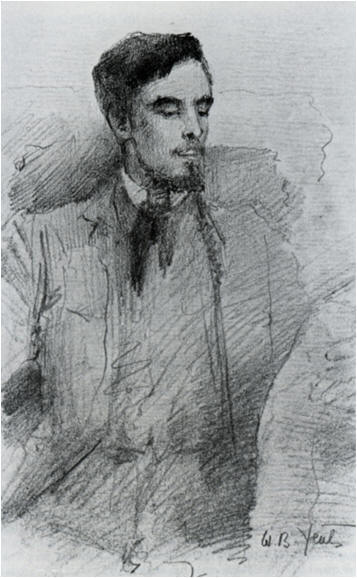

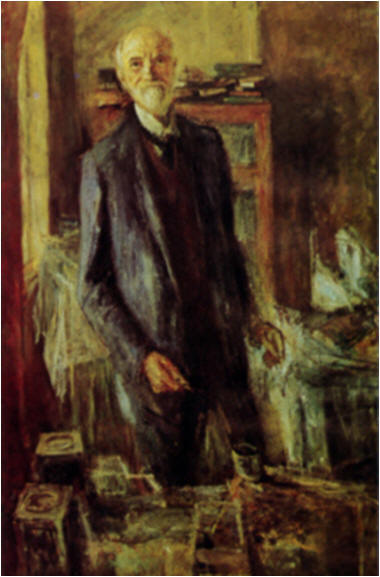

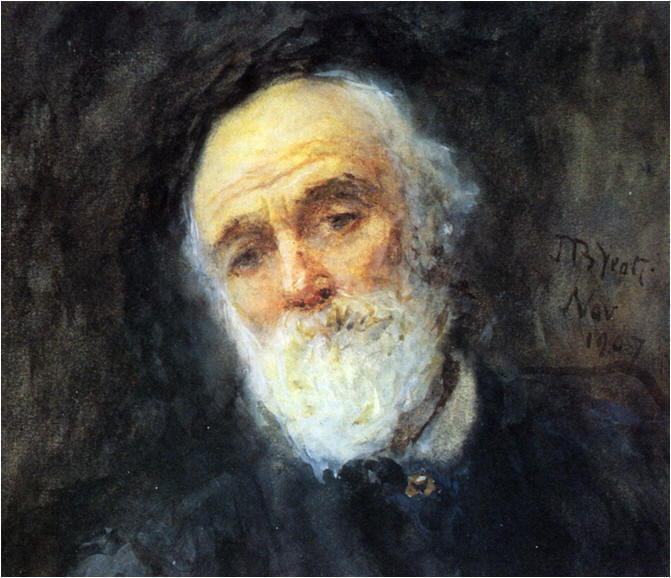

John Yeats had given up an early enthusiasm for the Pre-Raphaelites, and described himself in 1904 as ‘a born portrait painter … imprisoned in an imperfect technique’ (1997: 79).

[4]

Yeats described his father’s circle of friends in the Autobiographies as ‘painters who had been influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite movement but had lost their confidence’ (1999: 67). He remembered them with affection and sympathy, comparing John Nettleship somewhat extravagantly with Blake, finding in his work ‘in place of Blake’s joyous, intellectual energy a Saturnian passion and melancholy’ (1999: 142). ‘One of the sensations of my childhood’, he wrote, was ‘a description of a now lost design of Nettleship’s, God creating Evil, a vast, terrifying face, a woman and a tiger rising from the forehead’ (1961: 425). Nettleship came to specialize in representations of lions.

[5]

‘On

Mr. Nettleship’s Picture at the

The Lion, the world’s great solitary, bends

Lowly the head of his magnificence

And roars, mad with the touch of the unknown,

Not as he shakes the forest; but a cry

Low, long, and musical.

(1997: 496)

Another member of the circle, Frank J. Potter, was cherished for a very different kind of picture. Yeats recollected that his ‘exquisite Dormouse, now in the Tate Gallery, hung in our house for years’.

[6]

He also

remembered Potter’s predilection for a particular shade of dark blue, `a colour

that always affects me’ (1999: 67-8).

The relation between father and son was decisive in its influence on the son. Many of the young poet’s earliest conceptions about art and life were formed in his father’s studio. Later, differences in temperament became self-evident, and ‘It was only when I began to study psychical research and mystical philosophy that I broke away from my father’s influence’ (1999: 96).

[7]

The father’s desire to lead the

life of a gentleman-painter always struggled hopelessly with his inability to

create the means with which to do so. The brilliant conversationalist had other

failings: he was habitually incapable of declaring a painting complete. This

habit acquired mythical proportions after he moved to

[8]

[9]

Yeats wrote

of it shortly thereafter: ‘I have not seen this portrait, but expect to find

that he had worked too long upon it … that the form is blurred, the composition

confused, and the colour muddy. Yet in his letters he constantly spoke of this

picture as his masterpiece, insisted again and again, as I had heard him insist

when I was a boy, that he had found what he had been seeking all his life’ (1988:

152-3).

Father and son differed on the notion of art as imitation. The

son argued that art used the outer world ‘as a symbolism to express subjective

moods. The greater the subjectivity, the less the imitation’, adding that ‘The

element of pattern in every art is, I think, the part that is not imitative’ (1955:

223). The father had no sympathy for the son’s interest in the occult, in

politics, and in ingesting philosophical ideas into poetry. However, during the

more than dozen years of epistolary exchanges between New York and Europe,

father and son developed what Yeats referred to as ‘telepathic communication’ (1955:

251).

First, each in his medium excelled in the art of portraiture. Second,

their views on the notion of artistic personality concurred. In 1910, Yeats

wrote to his father, ‘Character is the ash of personality’ (1997: 128). The

father applauded the idea, developing it into the belief that the process of

true artistic self-expression was based on personality, not character. In 1912,

he criticized artists like Swinburne or Sargent for revealing mere technique,

for lacking ‘heart’ and ‘environment’, unlike the great serious painters of

Italy and Belgium, and ‘such painters as Hogarth’ (1955: 143). He compared

Rossetti unfavorably to Michelangelo in terms of the claim that ‘All art is reaction from life but never, when it is

vital and great, an escape’ (1955:

144). This idea has some relevance to the complex dialogue of the poem ‘Ego

Dominus Tuus’ (1915).

In 1922, the son compared portraits by Bernardo Strozzi and Sargent to claim that the contemporary portrait lacked a vital ingredient found in the Renaissance portrait: ‘unity of being’:

[10]

[11]

‘Somewhere about 1450 … men attained to personality in

great numbers, “Unity of Being” … Whatever thought broods in the dark eyes of

that Venetian gentleman has drawn its life from his whole body; it feeds upon

it as the flame feeds upon the candle’, whereas, ‘President Wilson lives only

in the eyes, which are steady and intent; the flesh about the mouth is dead,

and the hands are dead, and the clothes suggest no movement of his body, nor

any movement but that of the valet’ (1999: 227). The claim for a former unity

of being that is now lost may retain all the controversial element attached to

T.S. Eliot’s hypothesis about a dissociation of sensibility that is supposed to

have occurred in the seventeenth century; regardless, it is evident that between

father and son certain ideas were congruent, even when their expression

differed.

Third, father and son were of one mind about what they perceived

as ‘antagonism between a state of war and the practice of art and literature’ (1955:

247). In 1914, John Yeats described his idea of the poet as an individual characterized

by his capacity for multitudinous feelings, which imprison him in the world

that is poetry, while the man of action leaves the world of poetry when a

single feeling liberates him into action (1955: 187). A similar distinction

motivates the rhetoric of Yeats’s poem ‘On Being Asked for a War Poem’ (1915)

and in his elegy and obituary on Major Robert Gregory (1918). In ‘Ireland and

the Arts’ (1901) Gregory is treated as a hero for showing the result of what

Yeats believed was the need for artists to choose their subjects under ‘the

persuasion of their faith and their country’, which in Gregory’s case meant

being drawn to the grey mountains of Ireland’s west, ‘that are still lacking

their celebration’ (1961: 208-09). The tragedy of the talented Gregory was not

that he died young, in war, but that he chose to set aside his vocation for the

arts and accepted life and death as a man of action.

Turning to the relation between father and the younger son, we

note that both John and Jack were painters, but differed vastly in temperament

and the kind of art each practised. John was gregarious and irresolute; Jack

extremely private and quietly self-confident. [12] John painted only portraits; Jack experimented widely in all

sorts of genres, styles, and media. John wrote a little, in late life,

reluctantly; Jack wrote plays and narrative fiction from early on, and numbered

Beckett among his admirers. John had decided views on art; Jack practiced an art

that could not be less interested in art; a trait in which he also differed

from his poet-brother. George Moore remarked of Jack, in the context of a

similarity with John Synge, that ‘neither takes the slightest interest in

anything except life … Synge did not read

The poet and his brother were separated by age, temperament, and

by the environments each chose as homes during adult life. What they shared

were childhood memories of

III Blake

The father introduced his eldest son to the work of many poets,

including Shelley and Blake. Ironically, the visionary art of Blake provided

Yeats a natural ally against the belief, exemplified by his father, that the

business of the artist was to represent as well as he could the reality in

front of his eyes. Blake had scorned artistic practice based on ‘reasoning from

sensation’ (1961: 122), declaring that ‘No Man of Sense can think that an

Imitation of the Objects of Nature is The Art of Painting’ (Erdman 577). Blake

recognized imagination as ‘the first emanation of divinity’, and dismissed the

dictates of reason as ‘deductions from the observations of the senses’ and the

‘foolish body’ of ‘vegetative’ things (1961: 112-13). Yeats developed his

notion of antinomy from the Blakean idea that ‘Without Contraries is no

progression’ (2005: 27). [16] For

Yeats, the visionary mysticism of Blake differed from that of Swedenborg, who

seemed to him like Blake’s ‘angel sitting by the tomb’. In contrast, Yeats

would evoke what he called Blake’s own ‘more profound correspondences’ to ‘the

peaceful Swedenborgian heaven’ through the boys and girls ‘walking or dancing

on smooth grass and in golden light, as in pastoral scenes cut upon wood or

copper by his disciples Palmer and Calvert’ (1990: 12). [17-19]

From 1889 to 1893, Yeats worked with the painter, poet, and

scholar Edwin J. Ellis on an edition of Blake. Interest in this project went

hand in hand with an increasing absorption in spiritualism, occult phenomena,

and esoteric forms of wisdom. Yeats admired Blake’s illustrations to Young,

Blair, Milton, and The Book of Job.

Blake’s illustrations to Dante’s Inferno

and Purgatoria received special

praise for their ‘mystical pantheism’ and their ‘profound sympathy with

passionate and lost souls’ (1961: 144). He adored the illustration for

‘Francesco and Paola’ because it showed ‘in its perfection Blake’s mastery over

elemental things’ (1961: 126-7). [20] Even

Botticelli had not done better, he felt, because his art was ‘over-shadowed by

the cloister’, and able to achieve the ‘supremely imaginative’ only in the Paradiso (1961: 144). [21] In 1938, while at work on the

poem that became ‘Under Ben Bulben’, Yeats mulled over the Rilkean idea that ‘a

man’s death is born with him’, and at the end of a successful life, ‘his nature

is completed by his final union with it’. Yeats had found an apt image for this

approach to the idea of death in Blake’s design for Blair’s The Grave, in which the soul and body

embrace at death. [22]

Blake’s views on art had their effect on specific poems. For

example, Blake wrote of the line in graphic art as the defining boundary that

identifies shapes and forms in space: ‘The great and golden rule of art, as

well as of life, is this: That the more distinct, sharp, and wirey the bounding

line, the more perfect the work of art; and the less keen and sharp, the

greater is the evidence of weak imitation, plagiarism, and bungling’ (Mitchell

47, 60). ‘In Memory of Major Robert Gregory’ endorses the Blakean premise of a

conjunction between `the hard and wirey line of rectitude and certainty’ (Erdman

550). It commemorates the dead hero as having been born ‘To that stern colour

and that delicate line / That are our secret discipline / Wherein the gazing

heart doubles her might’ (236).

In A Vision, Yeats

placed Blake in Phase Sixteen, in which the artist finds within himself ‘an

aimless excitement’ and ‘a violent scattering energy’ which the intellect must

recognize as in part illusory (1990: 169). Yeats felt that Blake lacked models

and had to invent his own symbols. He was a Promethean spirit rebellious against

conventional norms in art and life. The struggle took its toll, leading Blake-Yeats

argued-to forms of expression that were sometimes confused or obscure. Blake’s

limited access to the achievements of the Venetian or Flemish traditions,

combined with his adherence to a technique anchored to ‘the bounding line’,

meant that Blake disparaged ‘shadows and reflected lights’ in painting as

concessions to ‘reason builded upon sensation’ (1961:133), leaving him with no

appreciation for what Yeats reveled in, the iridescent or glowing colours of

Titian. Blake practiced what Yeats concluded was `a severe art’, the product of

‘a too literal realist of the imagination’ (1961: 119).

IV The Pre-Raphaelites

Yeats recollected that as a young man, ‘I was in all things

Pre-Raphaelite … and once at Liverpool on my way to Sligo I had seen Dante’s Dream in the gallery there, a

picture painted when Rossetti had lost his dramatic power and today not very

pleasing to me, and its colour, its people, its romantic architecture had

blotted all other pictures away’. [23] In

the 1880s, Yeats was fed up of the kind of attitude that valued social realism

in painting: ‘“A man must be of his own time”, they would say, and if I spoke

of Blake or Rossetti they would point out his bad drawing and tell me to admire

Carolus Duran and Bastien-Lepage’ (1999: 114). [24] Yeats detested what he described as ‘Bastien-Lepage’s clownish

peasant staring with vacant eyes at her great boots’ (1999: 122). To him, such

art was a symptom of an age that had lost its impulse for the religious element

in life. He found this element latent even in the secular art of the

Renaissance: ‘Could even Titian’s Ariosto

that I loved beyond other portraits have its grave look, as if waiting for some

perfect final event, if the painters before Titian had not learned portraiture

while painting into the corner of compositions full of saints and Madonnas

their kneeling patrons?’ (1999: 115) [25]

Visiting the Tate Gallery in 1913, Yeats confessed to feeling overwhelmed

yet again by the Ophelia by Millais, and

Rossetti’s Mary Magdalene (1961: 346).

[26-27] Rossetti was respected for working

within a traditional symbolism, as with the lily in the hand of the angel in The Annunciation, and the lily in the

jar in Girlhood of Mary, Virgin. [28-31] His appeal was based on how he

could endow the faces of his women with what Yeats calls ‘perfected love’ (1961:

150), ‘imagination in the presence of beauty’ (1961: 351). Yeats’s Journal

entry for 17 March 1909 speaks of ‘The old art, if carried to its logical

conclusion, would have led to the creation of one single type of man, one

single type of woman … a poetical painter, a Botticelli, a Rossetti, creates as

his supreme achievement one type of face, known afterwards by his name’ (1999:

370). Yeats was equally fascinated by William Morris. He said that if he could have

lived any life but his own, he would have liked to live the life of Morris.

Failing that, he would have been happy to have worked with Rossetti and Morris

and Burne-Jones. For a time in 1857, the three worked as part of a larger team,

creating a set of murals for the Debating Hall of the Oxford Union Society. Yeats

was alluding to that project under the romantic notion that ‘I would be content

… to set up there the traditional images most moving to young men while the

adventure of uncommitted life can still change all to romance’ (1961: 347). There is some irony to his fantasy, since

the murals he romanticized-we are told-‘deteriorated beyond recognition within

a few years and now present a ruinous appearance despite repeated attempts at

restoration’ (Prettejohn 101). [32] Nevertheless,

Yeats’s attachment to an emotional complex that had its origins in

Pre-Raphaelitism and in Symbolist art remained unwavering throughout his life.

Yeats’s sister Lily worked for a time under Morris’s daughter,

May, at embroidery. [33] Yeats wrote

in 1890 of the debt owed by English society to Morris by praising his role in

promoting the culture of aesthetic consumption: ‘heavy tapestries and

deep-tiled fireplaces, hanging draperies and stained-glass windows that all

seem to murmur of the middle ages’ (1989b: 108). Yeats’s admiration for Morris found

special focus in the portrait by G. F. Watts. [34] The qualities he admired most in the man looked out from the

painting: ‘Its grave wide-open eyes, like the eyes of some dreaming beast,

remind me of the open eyes of Titian’s Ariosto,

while the broad vigorous body suggests a mind that has no need of the intellect

to remain sane, though it give itself to every fantasy: the dreamer of the

Middle Ages’ (1999: 131-2). [35]

Yeats’s predilection for Pre-Raphaelite art led naturally to

sympathy for the Aesthetic movement of the 1890s. Yeats saw himself surrounded

by diverse men of tragic genius. A younger contemporary, Max Beerbohm,

represented many of them in a memorable caricature. [36-37] Yeats was particularly taken up with Aubrey Beardsley, who

he later placed in Phase Thirteen of A

Vision (along with Baudelaire and Ernest Dowson), to illustrate ‘The

Sensuous Man’ (1999: 164). In 1894, Beardsley provided the poster for an Abbey

Theatre production featuring The Land of

Heart’s Desire. [38] A hue and

cry was raised about his illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s Salomé. George Moore, for example, complained of The Yellow Book, in which they appeared,

as the very ‘organ of the incubi and succubi’ (1999: 274). Yeats stood firm

behind Beardsley when the latter was ‘dismissed from the art-editorship of the Yellow Book under circumstances that had

made us indignant’ (1999: 248). He remained the proud owner of several

Beardsley prints, among them ‘The Climax’ and ‘The Dancer’s Reward’ (1999: 479,

n82), [39-40] and was fond of

recollecting that Beardsley told him that ‘I make a blot upon the paper’, ‘and

I begin to shove the ink about and something comes’ (1999: 254; 1940: 97). Ironically,

the notion that Beardsley did not need to labour in order to be beautiful has

been questioned by Beardsley’s modern biographer, who provides convincing proof

of a process of composition every bit as laborious as that of Yeats (Sturgis

121).

What fascinated Yeats most about Beardsley was not his capacity

to shock the public but the ‘emotional morbidity’ that enabled him ‘to take

upon himself the diseases of others’ (1990: 165). Yeats elaborated his views on

this trait into a little theory of what he called ‘victimage’, which claimed

that ‘Beardsley, after the manner of a medieval saint, took on “the knowledge

of sin”’ to enable “persons who had never heard his name to recover

innocence”’. Beardsley, however, denied all such arguments. He told an

interviewer, ‘What I am trying to do is show life as it really is’, adding that

‘I see everything in a grotesque way… Things have always impressed me in this

way’ (Sturgis 219-20).

After Beardsley’s death in 1898, Yeats became friends with two

other artists, Charles Ricketts and Edmund Dulac. Each played a significant

part in the poet’s life, providing many outstanding illustrations for his

books, and designs for some of his plays. Yeats became acquainted with Charles

Ricketts and Charles Shannon in 1899. They worked closely as painters and art

dealers. They also edited a journal and ran a press.

Contact with another artist and designer, Althea Gyles, was

confined to the 1890s. She prepared distinctive book covers for The Secret Rose (1897), Poems (1899), and The Wind Among the Reeds (1899). [44] In 1898, Yeats provided an enthusiastic essay to accompany

three of her images, describing her art as ‘full of abundant and passionate

life’, which brought to mind ‘Blake’s cry, “Exuberance is beauty”, and Samuel

Palmer’s command to the artist, ‘“Always seek to make excess more abundantly

excessive”’ (1975: 135). [45]

V A

Vision

Not all of Yeats’s interest in the arts was based on

personalities. He looked for a way to engage with ideas while retaining in his

poems the passion proper to art. He felt that ‘the casting out of ideas’ from

art was a ‘misunderstanding’ encouraged by the pursuit of technical refinement

(1961: 353). Like many other European artists and writers born in the latter

half of the nineteenth century, he held the belief that if art like that of

Shakespeare or Dante was to be possible again, the Western tradition had to be

enriched by resources from other cultures. Yeats’s Journal entry for 9 March

1909 speaks of ‘turning over the leaves of Binyon's book on Eastern Painting,

in which he shows how traditional, how literary that is’ (1991: 361). When he

had to imagine a feature in a painting that would avoid ‘the sense of weight

and bulk that is the particular discovery of

Yeats perceived a historical need for the imaginative arts to

remain ‘at a distance’ from ‘a pushing world’ (1961: 224). In Europe, he

argued, this distance had not been kept, as it had in Eastern cultures, hence

the need to ‘go to school in

When it came to Modern art, Yeats remained a cautious and reluctant

admirer. Before the turn of the century, Impressionism had become the latest

buzz word among painters, and wary of being caught out for lack of alertness to

the latest trends, Yeats made determined efforts to accommodate himself to what

filled him with distaste. Manet’s canvases, for example, left him nonplussed.

He wrote about them often with shock and puzzlement. [47-49] In the ‘Introduction’ to The Oxford Book of Modern Verse (1936), the emotional landscapes of

T. S. Eliot’s poetry and Manet’s paintings are described as pervaded by a

depressing ‘grey middle-tint’, which left him longing for ‘the vivid colour and

light of Rousseau and Courbet’ (1964: 224). Likewise, Yeats described the art

of Ezra Pound as ‘the opposite of mine’; conceding reluctantly that it was ‘as

characteristic of the art of our time as the paintings of Cézanne’ (1990: 72). The

same struggle against his own inclinations is evident in his endorsement of ‘the

cubes in the drawing of Wyndham Lewis’ and ‘the ovoids in the sculpture of

Brancusi’ as valid ‘stylistic arrangements of experience’ (1999: 86). [50] Elsewhere, Yeats was less benign:

in 1916, he wrote to his father, ‘I feel in Wyndham Lewis’s Cubist pictures an

element corresponding to rhetoric arising from his confusion of the abstract

with the rhythmical’ (Fletcher 174).

The most systematic arrangement of his views on art and history

was articulated through the writing of A

Vision (1925, rev. 1937). [51] Its

typology of human personality, combined with its cyclic account of history,

gave him an opportunity to survey the development of Western civilization

through authors and artists whose central characteristics were taken to

exemplify what he regarded as the logic of historical process and the logic of

the four-fold grid of Will, Creative Mind, Mask, and Will of Fate. For example,

Phase Sixteen shows ‘great satirists, great caricaturists’, types of ‘The

Positive Man’, who hate the ugly and pity the beautiful, which makes them

utterly unlike artists who pity the ugly and sentimentalize the beautiful, like

Rembrandt and Synge (1990: 171). Yeats used the latter two as illustrations of

Phase Twenty-three, in which, the artist is ‘never the mere technician that he

seems, though when you ask his meaning he will have nothing to say’. According

to Yeats, such artists have ‘eliminated all that is personal from their style’,

and show reality ‘without exaggeration’, while delighting ‘in all that is

willful, in all that flouts intellectual coherence’. He attributed to such

artists a capacity to work ‘in toil and in pain’, as in the patience shown by

Rembrandt ‘in the painting of a lace collar though to find his subject he had

but to open his eyes’, [52] or by Synge

in the many notebooks he filled with minute observations of his subjects. Above

all, he found that their work was ennobled by ‘a pity for all that lived’.

Ugliness, for Rembrandt, was ‘an escape from all that is summarized and known,

but had he painted a beautiful face … it would have remained a convention, he

would have seen it through a mirage of boredom’ (1990: 188-90).

The most extended discussion of art occurs towards the end of A Vision, in the chapter titled ‘Dove or

Swan’. From sculpture in Greek and Roman art, through the development of

Christian iconography, Yeats arranges the broad movement of historical change

to fit the pattern of his twenty-eight phases. The early achievements find

their culmination in Byzantine art: ‘I think that in early

How do subsequent painters fit into this overview of Western

history? Yeats places his answer ‘in the period from 1380 to 1450’, with

Masaccio, and developments that find their Renaissance culmination in

‘Botticelli, Crivelli, Mantegna, Da Vinci’. He describes this generation as

having arrived at the realization of a beauty in which ‘Intellect and emotion, primary curiosity and the antithetical dream, are for the moment

one’. Yeats distinguishes the forms that followed in Michelangelo, Raphael and

Titian as characterized by their capacity to ‘awaken sexual desire’. In his

view, later developments pale in comparison, offering little that is not ‘a

Renaissance echo growing always more conventional or more shadowy’ (1990: 274-9),

although how remnants of the past survive in later painting differs between,

say, Reynolds and Gainsborough. While a painter like Reynolds continued to live

‘content with fading Renaissance emotion and modern curiosity’, the ‘exhaustion

of old interests … is present in the faces of Gainsborough’s women as it has

been in no face since the Egyptian sculptor buried in a tomb that image of a

princess carved in wood’ (1999: 277). [53-54]

VI Poems

Yeats hardly ever wrote a poem that can be read as a mere verbal

representation of a visual representation. Poems in which the visual arts play

a significant role number over a dozen; a handful more make a point by alluding

to a painting or invoking a painter in minimal terms. Most of these poems were

written during the latter part of his career. There are several likely reasons

for this new mode of writing. Trips to Europe, like the one to Urbino in 1907, or

to

I shall first consider poems where the primary referent is

painting as an art-form rather than a specific painter or painting. In such

poems, the allusion functions as metonymy: painting represents the arts, which

represents an idea of civility, which represents the value celebrated by the

poet. Such allusions can be polemical, as in ‘To a Wealthy Man Who Promised a

Second Subscription to the

The 1912 poem intervenes in a public controversy. It exhorts a

reluctant patron to stop acceding to the philistinism of the

In ‘Meditations in Time of Civil War’, the section on ‘Ancestral

Houses’ invokes the traditional role of paintings among the aristocracy and the

landed gentry as part of an ordered way of life that the poet cherishes all the

more because it is now threatened with extinction:

What if the glory of escutcheoned doors,

And buildings that a haughtier age designed,

The pacing to and fro on polished floors

Amid great chambers and long galleries, lined

With famous portraits of our ancestors;

What if those things the greatest of mankind

Consider most to magnify, or to bless,

But take our greatness with our bitterness?

(309) [56]

While ‘Meditations’ is elegiac, ‘The Municipal Gallery

Revisited’ (1937) is celebratory. The poet offers solemn and self-conscious

congratulation to the nation for its great painters, housed in their principal

gallery, a collection enriched for the poet by personal associations with their

subjects: ‘Ireland not as she is displayed in guide book or history, but

Ireland seen because of the magnificent vitality of her painters, in the glory

of her passion’ (630): [57]

Around me the images of thirty years:

An ambush; pilgrims at the water-side;

Casement upon trial, half hidden by the bars,

Guarded;

Kevin O'Higgins' countenance that wears

A gentle questioning look that cannot hide

A soul incapable of remorse or rest;

A revolutionary soldier kneeling to be blessed;

An Abbot or Archbishop with an upraised hand

Blessing the Tricolour. ‘This is not,’ I say,

‘The dead

The poets have imagined, terrible and gay.’

(438) [58]

Yeats’s three gallery poems are types of what I shall call the ‘locational’

poem, each rooted to a specific place. They are complemented by ‘occasional’

poems, in which the role played by painting is tied to a specific time. In two

of them, the moment is the time of death. The first, ‘Upon a Dying Lady’

(1912-14), is about Aubrey Beardsley’s sister Mabel, who was suffering from cancer.

Like her brother, Mabel was a Roman Catholic. In the poem, because it is a

religious day, she turns the faces of all the dolls in her collection towards

the wall: ‘Pedant in fashion, learned in old courtesies’ (261). For the poet,

her action brings to mind the carefree times when Charles Ricketts made the

dolls, providing them costumes based on Aubrey’s drawings, or dresses made

familiar through Rococo costumes redolent of gaiety and indulgence, ‘Vehement

and witty’, like ‘the Venetian lady / Who had seemed to glide to some intrigue

in her red shoes, / Her domino, her panniered skirt copied from Longhi’ (261-2).

[59]

The second example of an elegiac ‘occasional’ poem is ‘In Memory

of Major Robert Gregory’ (1918). [60]

Recent biographical commentary suggests that the poet might have been much less

close to Robert Gregory, and Gregory less close to the vocation of painting,

than the poem implies. Regardless, Yeats celebrates the special gift he

attributes to the dead man, [61]

with an undercurrent of distress at how the pursuit of action in war had

deprived Irish art of a natural heir: [62]

We dreamed that a great painter had been born

To cold Clare rock and

To that stern colour and that delicate line

That are our secret discipline

Wherein the gazing heart doubles her might.

Soldier, scholar, horseman, he,

And yet he had the intensity

To have published all to be a world's delight.

(236)

So far we have looked briefly at two types of poem that refer to

painting in terms of a generic value. A third type identifies the painter as

the archetypal figure for the artist. In such poems, the artist either

‘eroticises the idea of the divine’ (Holdridge 1), or spiritualizes the erotic.

When the erotic is not in play, the painter sublimates the noumenal in the

phenomenal. There are three specific periods Yeats draws upon in this

enterprise: Byzantine art, Renaissance art, and the disciples of Blake.

Several poems commemorate the milder, pastoral manifestations of

the Blakean vision through allusions to Samuel Palmer and Edward Calvert. In

‘The Phases of the Moon’ (1918), Yeats uses the dialogue form to dramatize the

relation of thought to image through an exchange between his fictional

characters Aherne and Robartes, in which the seeker of ‘Mere images’ is at his

study in a high tower. He is identified as ‘

The lonely light that Samuel Palmer engraved,

An image of mysterious wisdom won by toil;

And now he seeks in book or manuscript

What he shall never find.

(268)

Blake’s disciples make another appearance in one of the last

poems written by Yeats, where Renaissance landscapes (meant to serve as background

for the human or divine foreground) lead to the tranquil art of Richard Wilson

and Claude Lorrain, and the epiphanic visions of Calvert and Palmer:

Gyres run on;

When that greater dream had gone

Calvert and Wilson, Blake and Claude,

Prepared a rest for the people of God,

Palmer's phrase, but after that

Confusion fell upon our thought.

(450-1) [64]

The phrase from Palmer that Yeats singles out describes Blake’s

illustrations to Thornton’s Virgil,

as ‘the drawing aside of the fleshy curtain, and the glimpse which all the most

holy, studious saints and sages have enjoyed, of that rest which remaineth to

the people of God’ (633).

The Renaissance gave Yeats the most secure sense of shared

values to which the most minimal allusion would suffice. That is how Leonardo

da Vinci makes an implied appearance in ‘Among School Children’:

Her present image floats into the mind–

Did Quattrocento finger fashion it

Hollow of cheek as though it drank the wind

And took a mess of shadows for its meat?

(324)

Michelangelo functions in similar fashion in several late poems.

In ‘Michael Robartes and the Dancer’ (1918), his sculptures offer a muscular

contrast to the opulent art of Veronese. The latter, like his other

distinguished Venetian brethren, is said to offer ‘proud, soft, ceremonious

proof / That all must come to sight and touch’. In contrast, Michelangelo’s

‘Morning’ and ‘Night’ show:

How sinew that has been pulled tight,

Or it may be loosened in repose,

Can rule by supernatural right

Yet be but sinew.

(282) [65]

Michelangelo makes another brief appearance in ‘An Acre of

Grass’ (1936). Here he is described as capable of conceiving divine beings who

can pierce clouds or ‘Shake the dead in their shrouds’ (419). He appears again

in ‘Long-Legged Fly’ (1937), the type of human mind whose concentration in the pursuit

of his gift produces a momentous outcome for human history. The refrain brings

Caesar, Helen, and Michelangelo together in an extraordinary analogy:

That girls at puberty may find

The first Adam in their thought,

Shut the door of the Pope's chapel,

Keep those children out.

There on that scaffolding reclines

Michael Angelo.

With no more sound than the mice make

His hand moves to and fro.

Like a long-legged fly upon the stream

His mind moves upon silence.

(463) [66]

‘Under Ben Bulben’ (1938) returns to Michelangelo, and his

depiction of ‘half-awakened Adam’. [67-68]

Here–alas–Yeats is disappointingly facetious in speaking of Adam’s capacity

to disturb

globe-trotting Madam

Till her bowels are in heat,

Proof that there's a purpose set

Before the secret working mind:

Profane perfection of mankind.

(450)

Classical and Byzantine art mattered as much to Yeats as the

Renaissance. Mosaic images occur in several late poems, such as the dolphins in

the final stanza of ‘

Astraddle on the dolphin's mire and blood,

Spirit after Spirit! The smithies break the flood.

The golden smithies of the Emperor!

(364)

Likely sources for the dolphin iconology have been identified

variously as a plaster cast in the

Straddling each a dolphin's back

And steadied by a fin,

Those Innocents re-live their death,

Their wounds open again.

(462)

The poem then turns to the evocation of another painting, Nicholas

Poussin’s Acis and Galatea, [70] which, when Yeats saw it, was

titled The Marriage of Peleus and Thetis.

The mistaken title ‘explains the appearance of that hero and his sea-nymph,

together with the substitution of Pan for Galatea’s lover, Polyphemus, in the

poem’ (1990: 173-4). [71]

Slim adolescence that a

nymph has stripped,

Peleus on Thetis stares.

Her limbs are delicate as

an eyelid,

Love has blinded him with

tears;

But Thetis' belly

listens.

Down the mountain walls

From where pan's cavern

is

Intolerable music falls.

Foul goat-head, brutal

arm appear,

Belly, shoulder, bum,

Flash fishlike; nymphs

and satyrs

Copulate in the foam.

(462)

The most well-known instance of a poem that derives its impetus

from a classical myth is the sonnet ‘Leda and the Swan’ (1923). [72] The parent myth has a long

tradition of representations in European sculpture and painting, from classical

to modern times. Commentators seem to agree that the most likely source-image came

from a photograph of a Roman bas-relief copy (in the British Museum) [73] of a Greek original, reproduced in Elie

Fauré’s History of Art (1921), of

which Yeats owned a copy: [74]

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

(322)

What is amazing about the sonnet is how the dramatic beginning

transports the reader from the purely brutal or the merely prurient to the

truly awe-inspiring. The awkwardness of the visual image is left behind, and so

is the physical absurdity of the myth, so that the poet can turn the evocation

towards the tremendous rhetorical question that becomes the point of the poem.

Elizabeth Cullingford notes that Faure's overheated commentary isolates

precisely the features of the bas-relief that attracted Yeats' attention: ‘look

at the “Leda” as she stands to receive the great swan with the beating wings,

letting the beak seize her neck, the foot tighten on her thigh--the trembling

woman subjected to the fatal force which reveals to her the whole of life, even

while penetrating her with voluptuousness and pain’. However, the basic point

made by Ellmann retains its validity, that in the poem, ‘we watch Leda’s

reaction, not the god’s’ (Cullingford 1994: 165-87; Ellmann 1964: x).

‘Leda and the Swan’ demonstrates how little of what makes a poem

powerful in its impact can be attributed to a visual source. We conclude that a

painting or an image offers very little by way of clue to how Yeats would use

it. We can think of the relation between the visual and the verbal in Yeats in

terms of three contraries. First, the visual is a significant part of aesthetic

experience, but the aesthetic is the lesser part of visionary experience. Hence

the materiality of the visual is prone to translation, as something other than,

and latent with, the greater. Second, Yeats valued subjectivity and

spontaneity, but quiddity of response was assimilated into a system whose

coherence becomes a more-than-aesthetic end in itself. It functions as a habit,

and we can end up either satisfied at its cohesiveness or irritated at its

totalizing intent. Third, Yeats argued passionately for the integration of the

arts into common life; in practice, however, he remained impatient with what

the ‘common person’ might think or want of art. Yeats subscribed to the logic

of the coterie and the elite; his views on art were rooted in personal

associations rather than aesthetic principles. His taste for art remained,

fundamentally, cautious and conservative.

Nevertheless, his work remains open to the most unexpected interactions

between the visual and the verbal. His power to transmute verbal

representations of the visual into complex figures of thought, feeling, form,

and idea grew stronger with age, making him an exemplary presence, not unlike the

visionary-clerk in The Celtic Twilight

(1893), whose poems ‘were all endeavours to capture some high, impalpable mood

in a net of obscure images’ (1959: 12). In the case of Yeats, we can replace

‘obscure’ with ‘exultant’ images. Regardless of Pater, and Lessing before him, we

can say of Yeats, using his words, that ‘He was going to try and apply to

painting certain fundamental principles of art which he had found true of

poetry. He was convinced that all the arts were fundamentally one art, and that

what was true of one art was, if properly understood, true of them all’ (1975:

343).

References

(Parenthetical numbers in the text refer to page numbers in Yeats’s Poems (edited by A. Norman

Jeffares, 1989).

Arkins, Brian. 1990. Builders of My Soul: Greek and Roman Themes

in Yeats. Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe.

Blake, William. 1988. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William

Blake. Ed. David V. Erdman. Commentary Harold Bloom.

Coote, Stephen. 1990. William Morris: His Life and Work.

Cullingford, Elizabeth Butler. 1994.

‘Pornography and Canonicity: The Case of Yeats' “Leda and the Swan”.’ In Representing

Women: Law, Literature, and Feminism, ed. Susan Sage Heinzelman and

Zipporah Batshaw Wiseman.

Ellmann, Richard. 1949. Yeats: The Man and the Masks.

Engelberg, Edward. 1988. 2nd

edition. The Vast Design: Patterns in

W.B. Yeats's Aesthetic.

Fletcher, Ian. 1987. W. B. Yeats and His Contemporaries.

Forster, R.F. 2003. W.B. Yeats: A Life, Volume 2: The Arch-Poet,

1915-1939.

Holdridge, Jefferson. 2000. Those Mingled Seas: the Poetry of W.B. Yeats,

the Beautiful and the Sublime.

Kiely, Benedict. 1989. Yeats’s Ireland: An Illustrated Anthology.

Loizeaux, Elizabeth Bergmann. 1986. Yeats and the Visual Arts.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 1978. Blake's Composite Art: A Study of the

Illuminated Poetry. Princeton:

North, Michael. 1985. The Final Sculpture:

Pierce, David. 1995. Yeats's Worlds:

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. 2000. The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Princeton:

Pyle, Hilary. 1993. Jack B. Yeats: His Watercolours, Drawings

and Pastels.

Schuchard, Richard. 1989. ‘Yeats,

Titian, and the New French Painting’. In Yeats

the European. Ed. A. Norman Jeffares. Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 142-59,

305-08.

Skelton, Robin and Ann Saddlemyer.

Eds. 1965. The World of W.B. Yeats:

Essays in Perspective.

Sturgis, Matthew. 1998. Aubrey Beardsley: A Biography.

Yeats, J. B. 1955. Letters to his son W. B. Yeats and Others

1869-1922. Ed. Joseph Hone. Preface, Oliver Elton.

Yeats, W. B. 1940. Letters from W. B. Yeats to Dorothy

Wellesley.

Yeats, W. B. 1959. Mythologies.

Yeats, W. B. 1961. Essays and Introductions.

Yeats, W. B. 1964. Rpt. 1970. Selected Criticism. Ed. A. Norman

Jeffares.

Yeats, W.B. 1975. Uncollected Prose. Vol. 2. Ed. John P. Frayne and

Yeats, W. B. 1986. The Collected Letters of W. B. Yeats, Volume

1 1865-1895. Ed. John Kelly. Assoc. Ed. Eric Domville.

Yeats, W. B. 1988. Prefaces and Introductions: Uncollected

Prefaces and Introductions to Works by Other Authors and to Anthologies edited

by Yeats. Ed. William H. O’Donnell. Houndmills and

Yeats, W. B. 1989. Yeats’s Poems. Ed. and annotated by A.

Norman Jeffares with an appendix by Warwick Gould.

Yeats, W. B. 1989b. Letters to the New

Yeats, W. B. 1990. A Vision and Related Writings. Ed A.

Norman Jeffares.

Yeats, W. B. 1997. The Collected Letters of W. B. Yeats, Volume

1 The Poems. Second Edition. Ed. Richard J. Finneran.

Yeats, W. B. 1999. Autobiographies. Ed. William H.

O-Donnell and Douglas N. Archibald.

Yeats, W. B. 2005. The Collected Letters of W. B. Yeats, Volume 4 1905-1907. Ed. John

Kelly and Ronald Schuhard.

_______________________________

List of

Images

[1 title]

2 WBY. 1887. Head of a

Young

3 WBY. c1903. Coole

Library. Pastel. MBY-AY. Loizeaux 10

4 JBY. 1903.

Self-portrait. Murphy 253

5 J.T.Nettleship. 1886.

Sketch of Refuge. Loizeaux 39

6 Frank Potter. 1880s.

Little Dormouse. NGL

7 JBY. 1888. William.

Murphy 153

8 JBY. 1911-22.

Murphy-f.

9 JBY. 1907.

Self-Portrait-detail. Kiely 126

10 Bernardo Strozzi.

Portrait of a Gentleman. Engelberg 92b

11 Sargent. 1917.

President Woodrow Wilson. NGD

12 JBY. 1899. Jack.

Murphy 198

13 JY. Synge.

Skelton-Saddlemyer-pl.5

14 JY. 1913. Backcloth

15 JY.

16 Blake. Marriage of H.&H.

p3.100. Fitzwilliam Library

17 Edward Calvert. Ideal

Pastoral Life

18 Edward Calvert. 1828.

The Bride

19 Palmer. 1850. The

Herdsman's Cottage

20 Blake. 1824-7.

Francesca and Paolo. Birmingham

21 Botticelli. Dante-Paradiso-26

22 Blake. R.Blair. The Soul hovering over the Body

23 Rossetti. 1871.

Dante's Dream.

24 Bastien-Lepage. 1877.

The Haymakers.

25 Titian. 1512. Portrait

of a

26 Millais. 1851-2.

Ophelia. Tate

27 Rossetti. 1857. Mary

Magdalene leaving the house of feasting. Tate

28 Rossetti. 1855-58. The Annunciation. Tate

29 Rossetti. The Annunciation-detail

30 Rossetti. 1848. Girlhood of Mary. Tate

31 Rossetti. Girlhood of

Mary-detail

32

33 Lily. Embroidery.

Abbey Theatre. Pierce

34 G.F. Watts. 1870.

Morris. NPG,

35 Titian. 1512. Portrait

of a

36 Beerbohm. Some Persons

of the Nineties

37 Beerbohm-detail. Wilde

& WBY

38 Beardsley. Poster.

Pierce 102

39 Beardsley. 1893. The

Climax. Salomé

40 Beardsley. 1894. The

Dancer's Reward. Salomé

41 Ezra Pound. C.1912. Sketch

of WBY

42 Edmund Dulac. 1915.WBY

& the Irish Theatre. Pierce

43 C. Ricketts. 1915. Deposition

from the Cross. Tate

44 Althea Gyles. 1899.

Book design.

45 Althea Gyles. 1898.

Noah’s Raven

46 Gauguin. Ta matete.

47 Manet. Les Bockeuses.

Schuchard 3

48 Manet. 1863.

49 Manet. 1870. Eva

Gonzales. Schuchard 7

50 Wyndham Lewis. 1911.

Self-portrait. Courtauld

51 Edmund Dulac. A Vision. Wheel.

52 Rembrandt. 1639. Portrait

of Maria Trip

53 Thomas Gainsborough.

1777. The Hon. Mrs. Graham (detail)

54 Fayoum Portrait,

c.120-130 AD.

55 John Singer Sargent.

1906.

[56 text]

57 Sir John Lavery. The

Blessing of the Colours. Kiely 131

[58 text]

59 Pietro Longhi. Colloquio tra baute (1750-60)

60 Charles Shannon.

Robert Gregory. Kiely 82-3

61 Robert Gregory.

[62 text]

63 Samuel Palmer. 1879.

The Lonely Tower.

64 Blake. 1821. Thenot

& Colinet. Virgil-Thornton. Loizeaux 75

65 Michelangelo. Tomb of

Giuliano de' Medici, Night and Day.

66 Michelangelo. Ceiling

of the Sistine Chapel (detail)

67 Michelangelo. Sistine

Chapel Ceiling: Genesis-Adam

68 Mosaic at

69 Poussin. 1630. Acis

and Galatea.

[70 text]

71 Leda.

72 Leda. Bas-relief.

73 Elie Faure. Image from

History of Art (1921). Cullingford 166.