|

The two "post"s |

|

1.1 Both terms have a post-(factor) in them. In one sense, they come after something else that is supposed to have happened prior to the occurrence of their referents. What we understand by them depends on how we understand that which preceded them, to which they are in some way related. 1.2 Both terms are poly-valent, ambiguous and highly contentious. 1.3 Post-colonial refers to colonialism as a fact of modern world history. It is thus a term whose field of reference is, in the first instance, political; and in the second, broadly societal and cultural, and then, literary. 1.4 Post-modern refers to modern, modernity, modernization and modernism, to each of which (and to each of their inter-relations) it refers in a poly-valent, ambiguous (and contentious) way. 1.5 Both terms have cultural and literary consequences through how politics interacts with economics and through how both affect the formation of societies, cultures, and literary values.

|

|

2 "Postcolonial" |

|

2.1Colonialism: a form of systematic and sustained control and administration of one set of territories (comprising peoples, communities and nations) by a nation or a people who see themselves in the act of colonizing as a community (of colonizers). 2.2 A preliminary task in dealing with post-coloniality (as a condition in which individuals and societies may be said to live) and post-colonialism (which may be described as an attitude to colonialism and its aftermaths) is to understand colonialism as a phenomenon in its unitary and its plural manifestations. 2.3 In the specific context of colonialism, this entails the involuntary effect accomplished, or the conscious policy pursued, by colonialists on behalf of the colonized. 2.4 In the specific context of post-colonial nations, this entails the conscious effort of the once-colonized to accomplish technological, economic, political, social and cultural progress to correspond to (or as an extrapolation from) that achieved by their former colonizer(s).

|

|

3 "Postmodern" |

|

3.1 Modern: A term to distinguish a condition or attitude or state of mind and a way of doing or regarding things in a way that is consciously contrasted and preferred to traditional or outmoded ways of thought and life. 3.2 Modern: A term used to describe the contemporary as different from, or radically discontinuous with, the past. 3.3 Modernization: The process by which each or several or all of the above are striven for by individuals, communities, a people, or a nation. 3.4 Types of modernization: technological economic political social cultural 3.5 Modernism: a set of cultural and literary attitudes and/or practices characterized by an acute sense of cultural crisis, radical ambiguities about modernization and its consequences for society and culture; a rejection of or radical discontinuity from tradition(s); technical experimentation conducted in a spirit of acute technical self-reflexivity; and a sense of malaise and/or alienation on the part of the writer or producer of cultural artifacts from the audience or consumer of cultural practices and products.

|

|

4 "Postcolonial writing" |

|

4.1 A body of writing whose unique relation to language and history gives it a dual role in contemporary societies. On the one hand, it bears witness to the residual force of colonial histories; on the other, it shows how that force may be turned to new forms of linguistic and cultural empowerment. 4.2 “Postcolonial” writing is held together as a notion by 3 factors: ● The global community constituted by English; ● The creative possibilities derived from assimilation/resistance to English as a language and a culture; ● The pattern of development shared between regions with a history of twentieth century decolonization. 4.3 “POSTCOLONIAL”: For me, the post in post-colonial does not just mean after, it also means around, through, out of, alongside, and against. (Albert Wendt, Nuanua: Pacific Writing in English since 1980, 1995). 4.4 In the most literal sense, any piece of writing is postcolonial which happens to be written from a place implicated in colonial history, by a person whose access to language has colonial associations. In a more dynamic sense, postcolonial writing shows awareness of what it means to write from a place, and in a language, shaped by colonial history, at a time that is not yet free from the force of that shaping. 4.5 ‘Postcolonial writing’ as a term is meant to sustain a stereoscopic perspective on the dialectical play between assimilation and resistance, or dependency and the will-to-autonomy, which constitutes the fundamental relation between writing and postcoloniality. Based on this definition, the reading methods we shall use in this module will look to writing for three kinds of synergy: ● between assimilation and resistance to colonial culture, ● between being shaped by and giving new shape to the colonial language, ● between the will to community and the will to modernity in an era of asynchronous decolonization. 4.6 The notion of ‘postcolonial writing’ acquires currency because the collapse of the modern European empires did not put an end to the derivativeness that prevailed, and in many cases persists, in cultural productions from the former colonies. ‘Postcolonial’ thus covers the gap between political self-rule and cultural autonomy. 4.6 The process of political decolonization took place over a large expanse of time, from the declaration of independence by America (1776) to self-government in the settler colonies: Canada, 1867; Australia, 1901; New Zealand, 1907; South Africa, 1910; and the Irish Free State, 1921. The dissolution of the British Empire became a sweeping reality during the period from 1947 to the early 1960s, when large parts of Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and Oceania became politically independent. The latest event in this process was the reversion of Hong Kong to mainland China in 1997. The six counties of Northern Ireland remain, in their unique way, the first and last region colonized by England, even if the Irish, like the Scots and the Welsh, also participated in the establishment of the British Empire. 4.7 The notion of “postcolonial writing” focuses on a single question that can be stated simply: what is the relation of Anglophone writing to the cultural aftermath of Empire? The answer takes many forms. 4.8 The first concerns language, and shows awareness, that the ‘standard’ forms of language often discriminate against minorities, marginal groups, women, the underclass and so on, albeit in different ways. Colonial writing was committed to the premise that British English could be used creatively without being constrained by its distance from Britain. Writers from the colonies chose to use English either because they were settlers of British descent, or because they were drawn to its expressive resources. In either case, mastery over English was aligned to its role as an instrument of modernity, progress, and cultural self-empowerment. 4.9 The second answer to the question of how writing relates to the aftermath of Empire concerns the will to localism. 4.10 The third answer to the question of how writing relates to postcoloniality concerns the dynamic relation set up by writing with colonial history. Writers revisit history as a zone of imaginative recovery and recuperation, like Orpheus trying to win back Eurydice from Hades. They solicit and raid history in order to understand how the colonial past led to their predicaments in the present. For them, writing is an attempt to construct knowledge about how the past, the present, and the future interrelate for societies and individuals yet to free themselves from colonial formations. 4.11 The fourth perspective on the relation of poetry to postcoloniality concerns the centrifugal force of diaspora, exile, and self-exile. In this perspective, individual and collective displacement are seen as part of the lasting fallout of Empire in a contemporary world that has replaced the ‘colonial’ dimension of experience with the ‘cosmopolitan’ or the ‘global’. Diasporic predicaments are emblematic of the transition from the global consequences of Empire to the realities of neocolonialism and globalization. Some of the writing we shall read for this module illustrates the ways in which writing seeks to mitigate the negative effects of alienation, isolation, and dispersal through the literal and symbolic activities of translation. 4.12 A note of qualification: ‘Postcolonial’ is premised on the assumption and hope that the former colonies are intent on maximizing their potential for literary autonomy. Where, and when, the potential for poetic and cultural autonomy is maximized, one can expect the term ‘postcolonial’ to become redundant and obsolete. Seen in this light, it is understandable that most writers are impatient with the term ‘postcolonial’, and resist its application to their work and aspirations. They argue that the term perpetuates dependency, homogenizes difference, simplifies complexity, misdirects reading, practises a form of nominalist colonization, and pushes literary uniqueness into a ghetto where academics fight over intellectual property while professing to bring writers from the margins closer to the metropolitan centre. 4.13 Any approach to the relation between writing and postcoloniality must also take account of the mechanics and politics of the production, circulation, and reception of imaginative writing as cultural capital. Publishing was a Western technological invention whose dissemination was part of the modernity brought to the colonies by the British. The publishing of fiction and poetry remained centralized in London for a large part of colonial history. Approbation remained local if a writer was admired only in the colonies; it became global when endorsed by the metropolis. The paternal aspect of metropolitan publishing was never easy to separate from its power as patron. Nevertheless, local canons, in all the settler and non-settler colonies, were invariably put together by local writers. 4.14 The absorption of ‘Commonwealth’ and ‘Postcolonial’ literatures into the academic canon opens a wider potential readership for new writing from outside the West. The scope for gaining new readers from the general reading public and the academic market is linked to how writers capitalize on the endorsement of discerning or empowering audiences. Questions such as who empowers endorsement, what constitutes discernment, who awards recognition, which criteria come into reckoning, and how recognition translates into canonicity constitute the cultural politics of the literary profession within which postcolonial – and all other –imaginative writing is read.

|

|

5 Clarifying "Modern/Postmodern" |

|

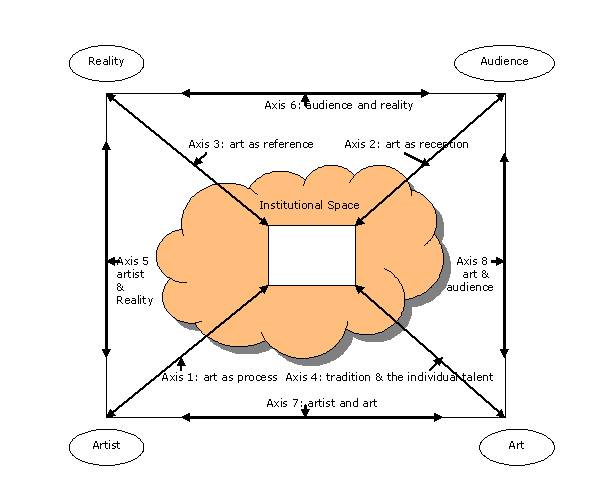

5.1 Since "postmodern" is notoriously diffuse as a term, and defers to and differs from the word it qualifies, the use of either term here might require a brief description. I shall recognize “modern” as mediated by two contrary manifestations: “modernity” (or “modernization’) and “modernism”. I read “modernity” as referring to a social project with utopian and Enlightenment origins, and “modernism” as referring to art practices whose implications can be treated either as symptoms of the influence of modernity on culture, or as the reaction of artists to the social and cultural consequences of modernity. I also distinguish between “postmodernity” and “postmodernism”, taking the first to refer to a cultural predicament, and the second to refer to an ideology of art practices. 5.2 I take “modernism” to refer to a phenomenon which found its most concentrated expression in European (and American) art during the early decades of the twentieth century. I use the term as a form of retrospective nomination that refers broadly to four forms of rupture in a traditional view of art. In terms of literature, the first affects the relation between the work as artifact and the poet as artist (a movement away from self-expression towards objectification), the second concerns the relation between the work and reality (a movement from relatively uncomplicated representation to an internalization of reference), the third concerns the relation between the work and audience (a movement away from giving the consumers what they expect), and the fourth concerns the relation between the work and the idea of literariness or literature (a movement towards greater self-reflexivity about the relation of the work to the historicity of literary forms, conventions, and traditions).

5.3 Artists and writers who were among the earliest and the most innovative in presenting these four relations in a state of acute crisis constitute the modernist generations; the artists and writers who respond to the sense of crisis with an attitude of belated (i.e. self-reflexive) irony can be called postmodern. I shall develop these claims while keeping in mind three features identified by Lyotard in “Note on the Meaning of ‘Post-’” (1988): the historical need to break with tradition and find a new direction, resulting in a rupture, a way of forgetting or repressing the past that repeats without surpassing; the coming to grief of human aspirations to knowledge and technology that were meant to lead to freedom and emancipation; and finally, creativity in the arts as a form of anamnesis, that is, a recalling to memory, with medicinal overtones of diagnosis and therapy. [Jean François Lyotard, The Postmodern Explained: Correspondence 1982-1985 [1988], trans. & ed. Julian Pefanis & Morgan Thomas (Sydney: Power Publications; Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1992) 75-80]. 5.4 A feature identified by Linda Hutcheon (from a Canadian perspective) as part of what brings the two “post-”s together: “a strong shared concern with the notion of marginalization, with the state of what we would call ex-centricity” [Linda Hutcheon, “Circling the Downspout of Empire: Post-colonialism and Postmodernism” [Ariel 20.4, 1989], rpt. The Post-colonial Studies Reader, eds. Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths & Helen Tiffin (London & New York: Routledge, 1995) 132]. 5.5 Another feature discussed by Hutcheon, the doubleness of irony: “doubleness is what characterizes not just the complicitous critique of the post-modern, but … the two-fold vision of the post-colonial”. 5.6 The postmodern is caught in the act of accepting a history whose shaping force is both acknowledged and turned in the acceptance. Between the two there is both commonality and tension. It seeks a closure to an ambivalence that cannot be resolved. The “post-” is part of a differend that cannot be resolved.

|

|

Last Updated 21 July 2010 |