|

Amir Khan: In Memoriam

Born on August 15,

1912 at Akola, in Maharashtra, Ustad Amir Khan passed away on February

13, 1974 at Calcutta in a strange and tragic car accident. In a

life-span of over sixty years, he spent almost forty years as a

vocalists in Hindustani classical music. He developed a unique style of

singing that is now known as the ‘Indore Gharana’.

Although born in Maharashtra, Khansaheb spent his childhood at Indore in

Madhya Pradesh. This place was inhabited by his ancestors and several

generations had migrated from Kalanaur in Haryana, and settled in Indore

under the patronage of the State. His father Shah Amir shifted to Indore

when Ameer Ali was barely two years old. Ustad Shahmir was an

accomplished Been and Sarangi player. Amir Ali loved his father so much

that later on he built a house in the ‘Bambai Bazaar’ area in Lane

number 3, and named it ‘Shahmir Manzil’. Every year he used to spend a

few months in this house.

Amir Ali’s mother passed away when he was nine years old and Shahmir

Khan had to take the responsibility of the entire family. By then he had

begun to teach music – vocal and sarangi - to both Amir Ali and his

younger brother Bashir. He used to take them to various musicians from

their ‘baradari’. On one such occasion, as soon as they entered the

house of a relative, ‘talim’ to the pupils was stopped suddenly and the

notebooks were closed promptly. Out of curiosity, Shahmir opened one

notebook and found notations of the ‘Merukhand’ gayaki. Someone snatched

away the notebook and shouted, ‘This is not for sarangi players, so what

is the use of reading it?’ Shahmir Khan left the house with his children

and decided to reply by training one of his sons in the ‘Merukhand’

gayaki. This was not easy since this gayaki was very difficult. What was

this gayaki and how was it sung?

Merukhand Gayaki

This gayaki is also known as Merkhand, Khandmeru, Sumerkhand or

Meerkhand. This is a composite word: Meru + Khand. The word ‘Meru’ has

many meanings: Merumani (name of a precious stone); Meruparvat (name of

a mountain); Merudand are well known words. ‘Meru’ means ‘sthir’, ‘achal’,

non-moving, fixed or steady; and ‘Khand’ means section. In the present

context, ‘Meru’ means fixed swars (notes) in a given raga. These notes

can be arranged in many different ways using the theory of permutations

and combinations. If there are only two swars, e.g., Sa and Re in a

given raga, then only two combinations SaRe and ReSa are possible. If

there are three, then six different combinations are obtained.

Proceeding thus, for seven notes in a raga such as Bhairavi, 5024

combinations [factorial seven] could be written down mathematically.

Musicians aspiring to learn this ‘Merukhand’-gayaki are trained to

remember all these combinations by heart and study these structures

constantly. He or she is also trained to select a few of these

combinations during performance and make a beautiful design of the

composition within the framework of the chosen raga. This method is

extremely difficult and Amir Ali’s father began to teach him after the

above-mentioned insulting incident. Considering his tender age, in the

beginning this ‘talim’ lasted for less than one hour a day. Later, when

young Amir Ali began to like it, the ‘talim’ continued for longer

durations. Soon he could remember the ‘Merukhand’ designs of three/four

swaras. For over five/six years, he learnt only ‘sargam’, ‘alankar’ and

‘palte’ to get familiar with ‘swar’ (‘swar-pehchan’). Then he was

introduced to the ‘Khayal’ style of singing. When his voice was about to

break at puberty, his father reduced the vocal ‘talim’ and began to

teach him the sarangi. After ‘Jummeki Namaz’, on every Friday, there

used to be a music concert in his house where many stalwarts would sing

or play. These included Ustad Rajab Ali Khan, Ustad Nasiruddin Dagar,

Beenkar Ustad Wahid Khan, Ustad Allah Bande, Ustad Jaffruddin Khan,

Beenkar Ustad Murad Khan, and Sarangi Nawaz Ustad Bundu Khan.

Amir Ali learnt a lot through these concerts while he also assimilated

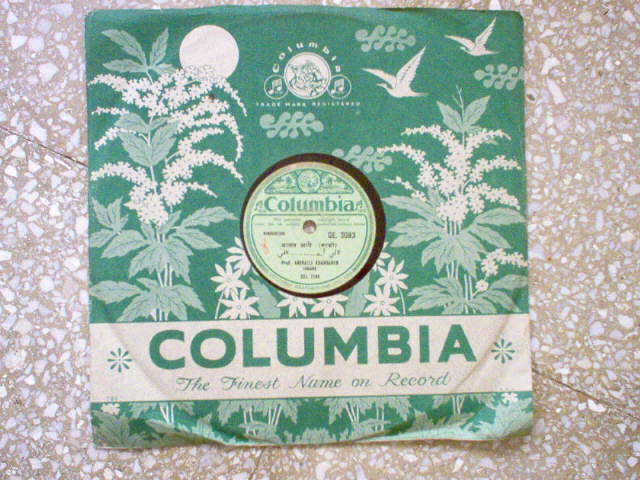

the ‘Merukhand’ gayaki. He came to Bombay around 1934 at the age of

twenty-two. He gave a few private concerts and also cut five/six records

with the ‘Gramophone Company’. These records were issued under a plum

coloured label with his name ‘Amir Ali, Indore’. The December 1934

catalogue of the gramophone company carries a special page on his

records with a photograph. In this photograph, he is seen wearing a

white turban and has ‘talwar’ cut moustache. Later, both the turban and

moustache disappeared as seen in the more well-known photographs of

later years.

This catalogue praises him and his gayaki in the following words:

‘Professor Amir Khan Saheb’s name is associated with the classical

music. He has earned many titles such as ‘Sangeet Shiromani’, ‘Sangeet

Sudhakar’ and ‘Sangeet Ratna’. Music lovers from various regions of

India have competed with each other in awarding these titles to Amir

Ali. One must listen to his music to get a cent-percent experience of

the celestial joy and happiness of Indian classical music. He has sung

raga ‘Shyam Kalyan’ with ‘sthayi’ on one side and ‘jalad phirat’ on the

other side of the record. In short, Khan Saheb’s record is a musical

feast’.

VE 1002 Aaj So Bana – Bhag 1 & 2 – Shyam Kalyan [actually, Puriya Kalyan]

Aaj So Bana Ban Aayori, Lad Ladavan De,

Banreke Shir Sahera Motiya Biraje, Banarike Mana Bihave

The record catalogues of this period are full of praise and

exaggeration. This was used for the publicity and as a marketing

strategy. This of course helped the company in the promotion of its

records. Amir Ali also recorded the following in the same session:

Multani (Dhola To Janam), Tarana in raga Todi, Hansadhwani (bhajan-Bhaj

Mana Nit Harike Naam), Suha Sugrai (Charan Paran), Kafi (Lalan Aaye),

Patdeep (Yeri Meri Aan), and Adana (Mohammad Shah Rangile).

It is not clear

whether these records were popular. It is also not known if they were

reviewed/advertised in magazines and newspapers. The Gramophone Company

has not re-issued them since they were first issued. They now remain in

the hands of die-hard record collectors scattered all over India.

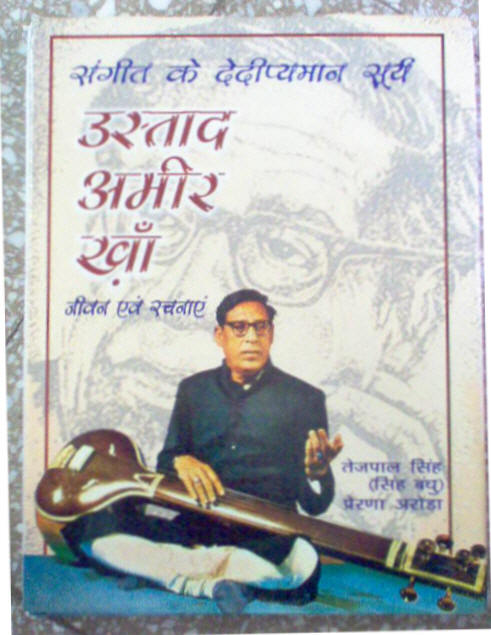

Recently, Pandit Tejpal Singh (the elder of famous duo known as the

Singh brothers), who was a senior disciple of Ustad Amir Khan, has

written a book on his master in Hindi. He has reviewed these records

with these words: ‘The music on these records is quite different and

shows the influence of the gayaki of Aman Ali Khan of Indore. He has

sung in the ‘safed teen’ scale. The ‘Sthayi’ and ‘Antara’ are sung twice

and in the beginning of each record. The Taans are fast and resemble

those of Rajab Ali Khan’.

Sangeetke Daideepyaman Surya: Ustad Amir Khan – Jeevan Aevam

Rachanaen (Kanishka Publishers, New Delhi, 2005)

Around 1935, several record companies (HMV, The Twin, Odeon, Jay Bharat,

Broadcast, and Young India) recorded the music of the great stalwarts of

Hindustani classical and light classical music. These include Professor

Abdul Karim Khan, Pandit Omkarnath Thakur, Prof. Narayanrao Vyas, Prof.

Shankar Rao Vyas, Prof. Aman Ali of Indore, Prof. Mallikarjun Mansoor,

Sau. Heerabai Barodekar, Bai Sunderabai of Poona, Miss Susheela Tembe,

Surshree Smt. Kesarbai Kerkar and Smt. Moghubai Kurdikar. These records

were very popular in their time. Mr. Keshavrao Bhole reviewed some of

them critically (under the pen-name ‘Shuddha Sarang’) in Marathi

periodicals and magazines. However, there was no review nor reference

nor even a mention of the records of Professor Amir Ali of Indore. What

could be the reason behind this?

The making of Ustad Amir Khan

The ‘Merukhand’ gayaki was probably found too academic by the common

listener and his concerts and the records were not very well-received in

Bombay. Amir Ali returned to Indore. After the death of his father in

1937, he had to shape his career to support the family. He decided to

change his singing style while keeping the ‘Merukhand’ gayaki at the

center of his musical personality. Usually a classical music concert is

divided into three parts: ‘Vilambit’ (slow) or ‘ativilambit’ singing

followed by singing in ‘Madhyalaya’, and concluded with a ‘drut’

composition using fast taans. Amir Ali decided to find three gurus for

these three sections. During his search, he found them in reverse order.

Ustad Rajab Ali Khan (1874-1959) of Indore knew Amir Ali since his

childhood. He used to call him by ‘Beta Amir’. Rajab Ali learnt

initially from his father Mughal Khan, then he learnt Been from Bande

Ali Khan and finally took lessons in the Jaipur gayaki from Ustad

Alladiya Khan, Thus, his gayaki became rich with multiple influences.

Listeners would say ‘Ustad Rajab, Gate Gajab!’. Amir Ali learnt the

style of ‘drut’ singing and very fast taans from Rajab Ali Khan and soon

commanded a mastery over that style. Ustad Rajab Ali Khan admired him by

saying that if you want to listen to the music of my young days, you

should listen to Amir Khan.

Ustad Aman Ali Khan (1884-1953) of ‘Bhendi Bazzar’ gharana was known for

his madhyalaya ‘Merukhand’ gayaki. Although he belonged to Indore, he

used to live in Bombay near the ‘Bhendi Bazaar’ area. During the days of

the British Raj, officers and residents used to live in spacious houses

near the J. J. Hospital. This was located behind the open market

(bazaar) and hence the commonly known address was ‘Behind the Bazaar’

that became known as ‘Bhendi Bazaar’. Many musicians lived in this area.

Thus the name ‘Bhendi Bazaar’ became associated with their style of

singing and gharana.

Ustad Aman Ali Khan never sang ‘ativilambit’ or ‘drut’ gayaki. He had

mastery over short taans with sargam in madhyalaya. He was also fond of

Karnatic music and the raga Hansadhwani was his favorite. He taught Amir

Ali for a number of years. Later on, Ustad Amir Khan used to sing Raga

Hansadhwani in his concerts in memory of Ustad Aman Ali Khan. He has

recorded ‘Jai Mate Vilamb Tajde’ on an LP record. In Karnatic music the

composition ‘Vatapi Ganpatim Bhajeham’ is very popular. He also recorded

a tarana in this raga – ‘Ittihadesta Miyan Ne Mano To’ [You (Allah) and

me are one and the same]. This Pharsi verse contains a spiritual message

of the one-ness between God and the devotee. This composition brought

great fame to Amir Khan.

For vilambit/ati-vilambit or slow singing Amir Ali chose Ustad Abdul

Wahid Khan (1882-1949) of the Kirana gharana as his model. Wahid Khan

was the cousin of Ustad Abdul Karim Khan and the guru of Smt. Heerabai

Barodekar. He was also known as ‘bahire’ Wahid Khan due to a hearing

deficiency. He was an accomplished Beenkar too. His style of

ornamentation and rendering ragas with the careful and delicate

treatment of each swar was unique. Amir Ali met Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan

very infrequently; he learnt his style less through personal contact

than by listening to his radio programs. Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan used to

sing in Jhumra Taal [‘Jhum Raha’ – means the rhythm that makes you

swing] and Amir Ali also began to sing in this wonderful taal. He had an

opportunity to sing in a private mehfil in which Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan

was also present and the master appreciated his music.

Thus, with rigorous practice and deep thinking, Ustad Amir Khan Saheb

began to emerge as a distinct musical personality. He got rid of his

erstwhile turban and moustache and began to appear on concert stage with

an uncovered head. This was quite a revolutionary step. If we recall the

photographs of old musicians, we find that male musicians either wore a

cap or a turban, and female musicians covered their heads with either

the ‘padar’ or the ‘pehlu’ of their saree or dupatta respectivley. Soon,

many musicians picked up his style, including Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar

Khan, Bhimsen Joshi and many others. Today, hardly any one covers his or

head while performing at a concert.

Ustad Amir Khan’s gayaki was a syncretic musical language, a kind of

re-mix or fusion of several gayaki styles. It could be accepted and

appreciated by music lovers as a mixture of the ‘Jaipur’, ‘Kirana’ and

‘Bhendi Bazzar’ gharana styles as inherent or latent in the ‘Merukhand’

gayaki. During his concerts, lovers of different gharanas could find

something to their liking, and hence his experiment became quite

successful. Thus, a new ‘Indore’ gharana emerged with Ustad Amir Khan.

Smt. Prabha Atre has written, ‘Although Sureshbabu Mane and Sau.

Heerabai Barodekar taught music to me, I have always considered Ustad

Amir Khan as my one of the gurus’. Pandit Bhimsen Joshi followed the

same pattern. His style assimilated the Jaipur element of ‘swar-lagao’

and the ‘taan kriya’ of Amir Khan, thus creating another re-mix within

the framework of his ‘Kirana’ gharana.

What were the specialties of the gayaki of Ustad Amir Khan?

Here is a list of some of them: ‘shantiprad swarlagao’, ‘dhairyapurna

gayan’, ‘sudh mudra’ and ‘sudh bani’, ativilambit laya, meaningful

pauses during singing, difficult but artful sargam, fast ‘gamakyukta’,

surel and danedaar taan ranging in all the three octaves, khayal and

tarana compositions consisting of Pharsi ‘sher’, verses and lyrics. He

used a six stringed tanpura. He never engaged in any ‘kusti’ or

‘akhadebaji’ with the tabliya. He used to sing the ‘sthayi’ twice. He

was six-feet tall, well-built, and would sit on the stage like a ‘sadhu’

or a ‘yogi’. In a concert, he used to sing with eyes closed or half

closed. His bandishes were chosen very carefully and had spiritual

lyrics. His bandish in raga Lalat (‘Jogiya More Ghar Aaye’) is an

excellent example which invokes a sage or a sadhu. It is interesting to

note that when Hindu singers were singing ‘Karim Tero Naam’ (Malhar) and

‘Alla Jane Alla Jane’ (Todi), Amir Khan was recording compositions

invoking Shiva, Hari and Rama (e.g., ‘Bhaj Man Harike Naam’ in

Hansadhwani, and ‘Jinke Mana Ram Birajae’ in Malkauns). He also created

the trend of continuous, uninterrupted singing of several ragas in

succession during a concert. In this style, he would begin the concert

with a raga and would not pause or stop after it was over. He would

immediately begin the next composition in another raga. This would give

a sense of continuity to his presentations.

Ustad Amir Khan witnessed the Royal patronage of music and also

performed in the period when private concerts, music festivals, radio,

cinema and gramophone records became the media that reached out to a

wider public. Each medium demanded a different kind of skill, but he

learnt and mastered each, and left his mark in all these media. As

mentioned earlier, he never sang thumri or gazal in his concerts. He

also did not sing or record the raga ‘Bhairavi’. He used to say

jokingly, ‘Do you think that my musical career is over? If not, then how

can I sing Bhairavi?’ He did not like singing either a Bhairavi thumri

or even a Bhairavi bhajan. He would say that Bhairavi is a ‘Sampoorna’

(complete) raga and must be treated like any other raga and sung

accordingly. He used to sing this raga very rarely in the company of

close friends. However, no recording of Bhairavi from him has been found

yet.

Amir Khan as a gramophone singer

Around 1945-50, Amir Khan was one of the topmost and most sought-after

vocalists in North India. He was invited to almost every important music

conference. Naturally, both the gramophone companies and the music

directors in Hindi/Bengali film industry approached him. With the bitter

experience of the 78-rpm records made in 1935, Amir Khan was rather

reluctant to commit himself to this medium yet again. G. N. Joshi of HMV

was a great fan of Amir Khan’s gayaki and would frequently attend his

concerts. He tried to persuade Amir Khan to cut new records for the

Gramophone Company. In his book Down Melody Lane (Orient Longman), G. N.

Joshi writes,

‘To obtain Amir Khan's agreement for the recording, I had to meet him,

and therefore it was incumbent on me to visit his residence. I was

greatly put off when I learnt about the locality where he stayed. I was

afraid of what people would say if they observed me entering a house of

ill repute. Any outsider would naturally draw his own conclusions, not

knowing that an eminent singer was living in that building. If I had,

out of fear or social stigma, refrained from going to visit Amir Khan,

his great artistry would have gone unrecorded. The idea of securing his

consent for recording together with a keen sense of duty prompted me to

enter the building, eyes downcast, not looking about me till I entered

Amir Khan's room on the third floor. Once in his room, I cheered up, and

I talked to him for an hour or two. After that I visited him often. We

exchanged views on music and gharanas, and such visits gave me

opportunities to study his likes and dislikes. These visits also gave

him confidence in me. After a couple of months and few such visits, he

agreed to come for a recording. Some more time was lost in persuading

him to agree to the terms of payment. Finally, this hurdle too was

crossed. Yet Amir Khan went on canceling dates, giving fresh ones and

then again postponing the recording on some flimsy grounds. I got fed up

with his dilly-dallying and, in spite of my great regard and respect for

him, I justifiably felt very annoyed. Ultimately one day I plucked up my

courage and said to him, 'If I had approached ‘God almighty’ as many

times as I have come to you, he would have blessed me, but all I can get

from you is the promise of a future date.' Seeing my exasperation he

became thoughtful, smiled a little and replied, 'Please do not

disbelieve me. Name any day of this week and I will keep the

appointment.’

‘True to his word he came on the day I named, and I got from him his

first long-playing disc. His favorite ragas were Marwa, Darbari Kanada

and Malkauns. It is indeed rare these days to hear Raga Marwa as

presented by Bade Gulam Ali and Amir Khan. His first LP was received

with tremendous enthusiasm by the record-buying public. This delighted

Amir Khan, and he was more than ready for another recording. In spite of

this I had to put in a lot of effort and time to bring him to the studio

again. This time he made an LP containing the ragas Lalit and Megh and

this was all that could be obtained from him before he was lost to the

world.’

This was in the year 1960. The LP record-cover for ragas Marwa and

Darbari has a black and white photograph enclosed in an oval shape

frame. Amir Khan wears a coat and rimless glasses and his portrait is

quite pleasant-looking. The Marwa uses the vilambit bandish ‘Piya mohe

anant das’ and the drut composition ‘Gurubina gyan kaise paun’. His

singing takes the listener to a spiritual world. In 1968, he recorded

his second LP: raga Lalit (Kahan jage raat, Jogiya more ghar) and Megh (Barkha

ritu aai and tarana). Its cover has a color-photograph with Khansaheb

wearing a blue suit. In 1980, he recorded his third LP with his most

favorite ragas – Hansdhwani (Jai mate vilamb tajde) and Malkauns (Jinke

mana ram biraje). The photograph on the LP record-jacket shows Khansaheb

wearing a white kurta and tuning his six string taanpura with eyes

closed.

These LP records are collector’s items today. Around 1960, he also cut

one 78-rpm record on the HMV label (N 88319). It contains raga Shahana

(‘Sunder angana baithi’) on one side and a tarana in raga Chandrakauns

on the other side.

Today, a Google search with the key words ‘Ustad Amir Khan’ yields over

55,000 hits. A discography of his available records/recordings is

available above and at:

http://www.pathcom.com/~ericp/ak_discography.html

Amir Khan as a

Playback singer

In 1952, at the age of forty, Ustad Amir Khan began to sing for films.

His first film was in Bengali - ‘Kshudhit Pashan’ or ‘Bhuka Patthar’ [A

hungry stone]. Ustad Ali Akbar Khan had set tunes as the music director

and Amir Khan sang the following songs:

1] ‘Kaise Kate Rajani’ - a bandish in raga Bageshree,

2] ‘Piyake Awanki’ – Thumri in raga Khamaj [with Protima Banerjee]

Pt. Debu Choudhury, famous Sitar player witnessed the recording of this

‘Khamaj thumri’ at the recording studio of ‘New Theater’, Calcutta and

it lasted from 11.00 p.m. at night till 5.00 a.m. next morning.

The Song text of the only recorded ‘thumri’ by Amir Khan Saheb is:

“ Piyake awanki main suniri khabariya, aang aang men umang uthat hai “

This film is occasionally telecast on Indian TV channels and one can

listen to Amir Khan’s music in the background score. If a VCD or DVD of

this film is ever released, then one will be able to listen again to

this music. However, the two songs are available on 78-rpm records,

which repose in the hands of record collectors in India.

In the same year 1952, another film, ‘Baiju Bawra’, was released and

Ustad Amir Khan contributed substantially as a consultant to the music

director Mr. Naushad Ali. Prakash Pictures’ ‘Baiju Bawra’ was set in the

‘Mughal’ period and is based on an encounter between two great singers,

Tansen and Baiju. Hindustani classical music was at the focus of this

film. It was unanimously decided that Amir Khan’s voice would be

suitable for the role of Mian Tansen. However, it was not clear who

should sing for the role of Baiju in the climax song during the singing

competition. Many names including Pandit Omkarnath Thakur were under

consideration. However, Amir Khan suggested the name of Pandit D. V.

Paluskar due to his ‘Prasadik’ (serene and devotional) voice. Pt.

Paluskar had by then cut several 78-rpm discs. Ustad Amir Khan and Pt.

D. V. Paluskar recorded a six minute jugalbandi in raga Desi (‘Aaj gavat

mana mero jhumke’) and a great recording was thus created. Paluskar

wrote down the notation of his part in a diary and this has been

published in a Marathi book ‘Parimal’ written by his disciple Smt. Kamal

Ketkar. Other Baiju songs (‘Tu gangaki mauj’, ‘Mana tarpat hari

darshanko aaj’) are sung by Mohammad Rafi. Viewers rarely notice the

fact that two different voices have been sued for the songs of ‘Baiju’,

a role played by the actor Bharat Bhushan. Today, no one even remembers

who played the part of Miyan Tansen in this film. However, the songs of

Tansen, in the voice of Ustad Amir Khan, are well-remembered by music

lovers as well as cine-goers. The title song of this film is a bandish

in raga ‘Puriya Dhanashree’ sung by Amir Khan. He had also sung an alap

in raga Darbari and recorded ‘Ghanan ghanan ghan garjo re’ in raga Megh.

This Megh composition was not included in the film. However, all these

three songs were released on 78-rpm records. Later, he also recorded a

composition ‘Daya karo re he giridhar gopal’ for the film ‘Shabab’

(again under the music direction of Mr. Naushad Ali). He did not receive

any payment for this recording, an omission noted in Pt. Tejpal Singh’s

book. Today, VCDs and DVDs of these films are widely available, and one

can listen to Amir Khan’s music from the Original sound tracks.

In 1955, the music director Vasant Desai invited Khansaheb to record the

Lalat composition ‘Jogiya mere ghar aaye’ for a Marathi film ‘Ye re

majhya maglya’, and a 78-rpm record was cut. The music director O. P.

Naiyaar recorded the same composition for the title song of the Hindi

film ‘Ragini’. Khansaheb has narrated, ’I was called for the recording.

The recording was over in just two minutes and was accepted. It was a

little over a minute and a half, and the time taken to tune the tanpura

lasted longer! If they had recorded my song for a little more time, they

would have obtained a three minute 78-rpm record’. This is an example of

how some of the renowned music directors had strange attitudes towards

classical music.

Khansaheb gave recordings for a few films produced by his disciples. Mr.

Mukund Goswami of Bombay produced two religious films. Amir Khan sang

‘Ae mori aali, jabse bhanak pari’, a composition in raga Darbari for the

film ‘Jai Shree Krishna’. In another film, ‘Radha Priya Pyari’, he sang

the same composition (‘Ae mori aali’) in jhaptaal. Another disciple, Pt.

Amarnath, produced a documentary film on Mirza Ghalib. Khansaheb sang

the famous Ghalib gazal ‘Rahiye aab aaisi jagah chalkar jahan koi na ho’

for this documentary. One does not know if these films (and the

documentary) are available today.

Amir Khan is best known for his playback singing in two films: ‘Jhanak

Jhanak Payal Baje’ (1955) and ‘Goonj Uthi Shahanai’ (1959). Mr. Vasant

Desai composed the music for both films. In ‘Goonj Uthi Shahanai’, he

has sung raga Bhatiyar (Nisa dina barasat) in a duet with the shehnai

played by Ustad Bismillah Khan. In a ragamalika duet, the two perform a

continuous set of eight ragas (Ramkali, Desi, Shuddha Sarang, Multani,

Yaman Kalyan, Sur Malhar, Bageshree and Chandrakauns) in just six

minutes. HMV released 78-rpm records of Amir Khan and Bismillah Khan

based on the recording for that film.

The title song, ‘Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje’, in Raga Adana, made him

famous throughout India and abroad. This was the high-point of the film.

During the recording of this song, the producer Mr. V. Shantaram was

quite restless since it was taking a long time to synchronize the chorus

with Khansaheb’s singing. Mr. Vasant Desai calmed him down and the song

made history. During the golden jubilee celebrations at Liberty cinema

in Bombay, Khansaheb was invited to sing this composition at the

ceremony and he sang it for a much longer duration. VCDs and DVDs of

both these films are now available.

What was the gharana of Khansaheb’s gayaki? He himself has replied,

‘Gharana is not known with any person’s name but is associated with a

place. ‘Indore’ was a place where many great musicians sang and played.

I have listened to many performers and put them together in a style and

named it as the ‘Indore’ gharana’. The musicologist Mr. Vamanrao

Deshpande mentions this gharana in his Marathi book ‘Gharandaj Gayaki’.

He describes it as a ‘swar-pradhan’ gayaki in which musical notes and

song/bandish text are important. Khansaheb was very particular about the

correct and meaningful pronunciation of words and notes.

Disciples

There is a common misconception that Amir Khan had no disciples: this

notion is dispelled by Pt. Tejpal Singh’s Hindi book. He has given

details of Kahnsaheb’s ‘Ganda-baddha’ disciples with photographs. Some

of his disciples were:

Delhi – the late Pt. Amar Nath, Tejpal and Surinder Singh (Singh

brothers), Munir Khan (sarangi player), Ajit Sinh Pental, Amarjit, R. S.

Bisht, Shankar Majumdar.

Calcutta – A. T. Kanan, the late Shreekant Bakre, Smt. Purvi Mukherjee,

the late Pradyumna Mukherjee, Kankana Banerjee, Sunil Banerjee.

Jalandhar – Shankarlal Mishra, Surendra Shankar Awasthi.

Simla – Bhimsen Sharma.

Indore – Narayan Rao, Devbaksha Pawar.

Rajkot – Gajendra Bakshi.

Bombay – Mukund Goswami [mentioned above as film producer of two

religious films].

Mr. Mukund Goswami was the Mathadhish (chief priest) of the temple of

Vallabhacharya Sampradaya (cult) in Kalbadevi area in Bombay. He was the

devotee of Khansaheb’s music and learnt music as a disciple. He used to

play the Saraswati Veena. Khansaheb sang at the temple on a number of

occasions and excellent recordings of his singingf are preserved in the

collection of this Sampradaya.

Pt. Gokulotsav Maharaj of Indore is also mentioned as an indirect

disciple. This is because he never met and learnt from Khansaheb but

learnt from radio programs and recordings. He imitates Amir Khan’s

gayaki very well. Bhavnagar’s Pandit Rasiklal Andhariya, Mumbai based

sarangi player Sultan Khan and the sitar player Pandit Nikhil Banerjee

from Calcutta also show the influence of Khansaheb’s gayaki.

Exploring the origins of the Tarana

Perhaps the greatest contribution of Ustad Amir Khan to Indian music is

his study of the Tarana form. He was awarded a fellowship by Bihar

Academy. It is not clear whether his research and findings were recorded

and whether these are available with the Bihar Academy in print or in

any other form. He researched the Tarana form quite thoroughly, and used

to sing taranas in almost every concert. Sometimes, he used to explain

the tarana composition and its meaning.

The tarana is believed to have origins in the 13th century. The great

poet, musicologist and administrator Amir Khushro was a disciple of

Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia (Avalia). Amir Khushro composed taranas for his

guru. After the death of Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia, Amir Khushro spent the

rest of his life at his tomb and composed a number of taranas. He

breathed his last at the tomb of his guru. Today, Hazrat Nizamuddin is a

Railway station in Delhi and an express train is named after Hazrat

Nizamuddin.

Amir Khushro’s work consists of the poems with verses containing

specific words which are repeated during a vocal performance. These

poems/verses are devotional in nature. In any religious song, repetition

of words is necessary. These repetitions are useful to devotees in

reaching towards God or Allah through ‘Nama Smarana’ or ‘Japa’. In the

Sufi cult, music is used invariably in singing taranas. The meaning of

some of the ‘Pharsi’ words used in taranas are:

Dar – Bheetar, Aandar (inside)

Dara – Andar Aa (get in or come inside)

Dartan – Tanke Aandar (inside the body)

Tanandara – Tanke Aandar Aa (Come inside the body)

Tom – Main Tum Hun (I am you)

Nadirdani – Tu Sabse Adhik Janata Hai (You know more than anyone else)

Tandardani – Tanke Aandarka Jannewala (One who knows what is inside the

body)

One of the simplest tarana compositions is this: “ Dara dara dartan,

darat dartan dartan “

It means: ‘Aandar Aao, Tanke Aandar Aao’

Simple words used for addressing Allah are:

‘Ya La La La Lom’, which means Alla, Alla repeated several times.

Ye, Yali, Yale, Yala, Yalale: these are short forms of ‘Allah’.

Kumar Gandharva has sung the tarana ‘Yala Ya Yala Yallari’ which is

available on tape and CD. However, the inlay card does not explain the

meaning of these words and the purpose of this tarana. If music

companies and musicians take the trouble to explain their significance

to uninitiated listeners, music lovers will benefit a lot.

A tarana is usually sung by Sufi saints during their prayers. They sing

taranas in a state of trance or in a ‘Hal’ mood. Often, they dance

during the state of ecstasy. Unfortunately, due to various reasons,

musicians did not take the trouble to understand the meaning of these

‘pharsi’ sher and words. They treated these compositions merely as a way

of showing off their skill in fast tempo singing. Today, if anyone wants

to know what a tarana really means, then over 400, 000 sites can be

visited on the internet. The most common description of the tarana is

reproduced below from two representative sites:

‘1] Taranas are songs that are used to convey a mood of elation and are

usually performed towards the end of a concert. They consist of a few

lines of rhythmic sounds or bols set to a tune. The singer uses these

few lines as a basis for very fast improvisation. It can be compared to

the Tillana of Carnatic music.’

‘2] Tarana: This is a vocal composition that is usually sung in a fast

tempo using syllables such as na, ta, re, da, ni, odani, tanon, yalali,

yalalam, etc. Sometimes, Pakhawaj bols or Sargams are also used. The

difference between the Drut Khayal and Tarana lies in the text. In the

Khayal, the fast type is usually a meaningful poem while in a Tarana,

there is no poem as such and the emphasis is on producing rhythmic

patterns with vocables. The Tarana is set to a raga and Tal. The Tal can

be Teen-tal, Ek-tal, Jhumra, Ada-chautal and so on and its tempo can

range from Vilambit to Drut. Tarana singing requires specialization and

skill in rhythmic manipulation. The late Amir Khan, Nissar Hussain Khan,

Krishnarao Pandit and Kumar Gandharva were known for Tarana singing, as

well. Among the present day singers, Ustad Rashid Khan, Veena

Sahasrabuddhe, Padma Talwalkar and Malini Rajurkar include this form in

their repertoire. The Tarana can have bols of Sitar, Pakhawaj and

Mridang too, in addition to Sargams.’

According to Ustad Amir Khansaheb, due to the ignorance of the meaning

of the words from a foreign language, many musicians added the tabla,

pakhawaj and mrudangam bols to the tarana (e.g. Dha Kid Tak Dhum Kid Tak

etc.) and distorted the form completely to please the audience. They

exhibited the ‘taiyyari’ of their tongue to the listeners, but defeated

the purpose of the tarana totally. Ustad Amir Khan was seriously

concerned about this neglect, and he tried to enlighten listeners by

singing taranas in many of his concerts and recordings. He has recorded

the following taranas, though relevant information about them (as given

below) is missing from the inlay cards/record covers.

1] Tarana in raga Suha:

‘Sakiya Barkhej Dar Deh Jamra, Khaq Bar Sar Kun Game Aayyamra’

Meaning in Hindi: ‘Ae saki! tu uth ja, mujhe jam de aur duniyaki

taqliphonke sarpar khaq dal’

2] Tarana in raga Megh:

‘Abre Tar Saihane Chaman, Bulbul O Gule Phasale Bahar

Saki O Mutrib O May, Yaar Be Saihane Guljar’

Meaning in Hindi: ‘Badal bheege hain (phuhar baras rahi hai), aangan men

chaman hai, wahan bulbul (bhi) hain, bahar ka mausam hai, saki hai,

gayika hai, sharab hai aur chamanke aanganmen mera mehboob maujud hai’

3] Tarana in raga Hansadhwani:

‘Ittihadista Miyane Mano To, Mano To Nista Miyan Ne Mano To’

Meaning in Hindi: ‘Tere aur mere daryanmen ek aaisa talluk hai ki tere

mere beech men main aur tu ka fark nahin raha gaya’ (One-ness of the

mortal and immortal)

Personal life

It is a matter of debate whether one should discuss the personal life of

any legendary artist in public. Some argue that it helps in

understanding the musician in his totality, and hence it is useful to

study the personal aspects that have shaped the artist. The life of

Ustad Amir Khansaheb was full of struggle. The period in which he was

trying to establish himself as a professional artist was a difficult

one. Royal patronage was diminishing gradually. The struggle for

independence was at its peak and naturally performing arts did not have

ample backing and support in society. During 1932 and 1942 he moved from

place to place like a ‘fakir’. Initially, he lived with his maternal

uncle Mohammad Khan in Arab Lane, Bombay. Here he met Amanat Ali Khan,

nephew of Ustad Rajab Ali Khan. Soon they became close friends. Juggan

Khan, a table player introduced Amir Khan to Prof. B. R. Deodhar at his

office in Dadar. He sang for him on a number of occasions. Later, Prof.

Deodhar wrote about him in ‘Sangeet Kala Vihar’ – a magazine of the

Gandharva Mahavidyalaya. In 1934/36, he also gave private tuitions in

Bombay.

In 1936, his father asked him to join the services of Maharaj Chakradhar

Singh of Raygadh Sansthan in Madhya Pradesh. The Maharaj used to sponsor

musicians and send them to many music festivals and conferences. Soon he

sent young Amir Khan to participate in the Mirzapur Conference. There

was a galaxy of musicians at this conference: Faiyaaz Khansaheb, Inayat

Khan Sitariye (father of Vilayat Khan), Pandit Omkarnath Thakur and Smt.

Kesarbai Kerkar. Amir Khan sang in the ‘Merukhand’ style and the

audience hooted him out in a few minutes. The organizers appealed him to

sing a thumri, but he refused and left the concert stage. Soon he left

the Royal court and returned to Indore. His father died in 1937.

Khansaheb lived in Bombay until 1941 and then went to Delhi to teach

Munni Begum, former disciple of Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan. (Later on he

married Munni Begum). In Delhi, he used to live in Sadik Building on G.

B. Road. He spent some time in Calcutta and used to live in the area

inhabited by dancing (nautch) girls and ‘kothewalis’. He sang in a

Lahore conference just before Partition. Soon after Independence and

Partition, the atmosphere in Delhi and Calcutta was quite changed.

Hence, Khansaheb came to Bombay. He used to live near Congress House on

Vallabhbhai Patel Road on the third floor in the room next to Gangabai.

This place was full of prostitutes and singing girls and the area was

known as ‘Pila House’. Ustad Bade Gulam Ali Khansaheb, Ustad Ahemadjan

Tirakhawa, and Ustad Abdul Wahid Khansaheb had also lived here, since

they would get tuitions and disciples in this area. The atmosphere of

the area never disturbed these musicians in their ‘talim’ and teaching.

Khansaheb used to live here like a sage. Later on, he could afford to

move to ‘Vasant’ building on Pedder Road, where he lived for the rest of

his life.

Khansaheb’s first ‘Nikah’ nama (marriage contract) was with the sister

of Sitar Player Vilayat Khansaheb. Her name was Zeenat, and he used to

call her ‘Sharifan’. At that time, he was struggling and had a meagre

income. This marriage did not last long. They had one daughter ‘Fahmida’,

a charming, fair and tall lady resembling Khansaheb. She is now a

leading homeopath in Bombay. Then he married his disciple Munni Begum of

Delhi. This marriage lasted quite a long time. Khansaheb used to call

her ‘Khalifan’ and his disciples would call her ‘Amma’. She loved and

cared for them like a mother. He had a son from this marriage: Ikram.

This son did not have any interest in music. He studied Mechanical

engineering, settled in Canada and in 1969 invited Khansaheb to Canada

and organized a few concerts for him. Around 1965, Khansaheb married

Raisa Begum, daughter of the thumri singer Mushtari Begum of Agra. He

had expected that his second wife, Munni Begum, would accept the third

wife. But she could not bear the shock and left home and was never seen

again. It was rumored that Munni Begum drowned herself in Prayagraj near

Allahabad.

In 1966, Raisa Begum delivered a son. A grand party was thrown and a

wonderful jalsa was organized in Indore. His first birthday was

celebrated at Karolbaug in Delhi. He was called ‘Bablu’ and registered

in school as ‘Haider Amir’. Khansaheb passed away when he was eight

years old. After securing a B.Com degree he began to act on stage. Using

the stage name ‘Shahbaz Khan’ he began to appear in films and in TV

serials. His role of Haider Ali in TV serial ‘Tipu Sultan’ was very

popular. Thus we see that the musical heritage of Ustad Amir Khan was

not carried forward by his children. His younger brother Bashir Khan was

a staff artist at Indore radio station and retired as a ‘Sarangi’

player.

Sunset

February 13, 1974. Khansaheb was in Calcutta. After dinner at a friend’s

house, he was returning in a car with a journalist friend, Shams-U-Jaman,

and a disciple, Smt. Purvi Mukherjee. They were discussing Urdu

literature. In the Southern Avenue area, they were traveling down Lanes

Down Road. All of a sudden, a car from the opposite direction collided

with their vehicle. The collision caused both cars to spin twice before

colliding with each other again. Khansaheb was sitting near the door. On

impact, the door opened and he was thrown out. He hit a nearby electric

pole twice asa consequence of the sudden fall. His journalist friend and

Purvi Mukherjee survived, but the driver died on the spot and Khansaheb

passed away one hour later in the hospital. He breathed his last near

the home of his first wife Zeenat. His last rights were performed by his

former brothers-in-law: Ustad Vilayat Khan and Ustad Imrat Khan. He was

buried in ‘Gobra Kabrasthan’. Later, his son Ikram decorated this tomb

with ivory stones. Khansaheb had planned to leave for America with Mr.

Govind Basu and Pandit Nikhil Banerjee. He had been invited to visit San

Francisco University as a Visiting Professor for one year. However, his

fate had decided differently.

The sudden demise of Ustad Amir Khansaheb left the world of music

shocked and grieving. Indore radio organized a special broadcast and

someone in the program said, ‘Teesare saptak par thahari taan aapni

jagah tham gayi’ [The taan that reached third octave remained there and

did not descend]. His disciples commemorated the anniversary of his

death for many years.

In 1976, HMV released an LP record from the live concert recordings of

Ustad Amir Khan. In 1981, the INRECO Company released a record and tape

of raga ‘Chandramadhu’. His disciples Singh Bandhu, Kankana Banerjee and

Purvi Mukherjee recorded ragas and paid musical tributes to their guru.

Many music lovers have been collecting the recorded music of Ustad Amir

Khan from before his demise. What was (and is) so great about his music?

That is what future generations shall find out by listening to his

legacy of recordings.

- Suresh Chandvankar

Society of Indian Record Collectors, Mumbai

|