EL1102 Studying English in Context 00/01

Notes for Lecture No. 3 (Part 1)

1.

What is grammar?

grammar

(organisation of words into sentences)

lexis (organisation of words — arrangement and choice)

phonology (organisation of sounds)

I don’t want to talk grammar. I want to talk like a lady. [Eliza Dolittle in Pygmalion]

I

used to get mad at my school,

the teachers who taught me weren’t cool,

holding me down, turning me round,

filling me up with your rules … [The Beatles]

[G]rammar

for linguists is the level of their analysis of linguistic structure which

concerns the organisation of words into sentences. [Leith 1983, p. 92]

ALL

languages and ALL dialects have ‘grammar’.

Different

‘levels’ of grammar

How

would you divide up this sentence?

My

first sight of England was on a foggy March night in 1973 when I arrived on the

midnight ferry from Calais. For twenty minutes, the terminal area was aswarm

with activity as cars and lorries poured forth, customs people did their

duties, and everyone made for the London road. [Bill Bryson, Notes from a

Small Island (1995), p. 11]

‘comma

units’? — informal

For twenty minutes, || the

terminal area was aswarm with activity as cars and lorries poured forth, ||

customs people did their duties, || and everyone made for the London

road.

more

‘meaningful’ bits that can be isolated?

For twenty minutes, the

terminal area was aswarm with activity || as cars and lorries poured forth, ||

customs people did their duties, || and everyone made for the London road.

Definition

of clause (tentative)

[W]e

have to be able to combine words into meaningful message structures and the

most fundamental message structure in any language – in terms of a message that

has any sort of completeness about it – is a clause. [Butt et al. 1995:

35]

Clauses

into phrases

For twenty minutes, | the

terminal area | was | aswarm with activity

Phrases

of more than one word, eg

For twenty minutes

the terminal area

Words

into morphemes (note: different from syllables)

fog-gy

arriv(e)-ed

mid-night

a-swarm

act-iv(e)-ity

We

can therefore break down the sentence into the following components.

A sentence is made up of one or more clauses;

a clause is made up of one or more phrases;

a phrase is made up of one or more words; and

a word is made up of one or more morphemes.

Analyse

this?

Then

abruptly all was silence and I wandered through sleeping, low-lit streets

threaded with fog, just like in a Bulldog Drummond movie. [Notes from a

Small Island, p. 11]

Then

| abrupt-ly | all | was | silence || and | I | wandered | through sleep-ing,

low-lit streets threaded with fog, | just like in a Bulldog Drummond movie.

2.

Dialects

regional

dialects and class dialects

The

difference between accent and dialect seems relatively simple to describe: accent

consists of pronunciation; dialect consists of grammar, words and their

meanings, and pronunciation. [Graddol 1996, p. 270]

Dialects

are language varieties which differ from one another grammatically as well as

in other ways. People who say I ain’t got none are speakers of a

different dialect from those who say I haven’t got any. [Andersson and

Trudgill 1992, p. 165]

POPULAR

USAGE: language v. dialect (language = standard variety; dialect

= non-standard variety)

USAGE

BY LINGUISTS: all varieties (standard or non-standard) = dialects

Example:

in Chinese dialectology: Mandarin, Cantonese, Hakka, and Min (Hokkien, Teochew)

dialects.

Example

of English dialects: English, Scottish, Irish, Canadian, American, Jamaican,

New Zealand, Pakistani, Singaporean and South African dialects. And within

England, we can go further and talk about the Yorkshire dialect or the Cockney

dialect of English.

Some say: ‘A language is a

dialect with an army.’

The

examples above have been mainly regional dialects. We can also talk about

working-class dialects or upper class dialects.

3.

Getting hold of data

(a)

introspection (grammatical v ungrammatical? usual v unusual?)

PROBLEMS

(b) use informants

The

informant is not a teacher, nor a linguist; he is simply a native speaker of

the language willing to help the linguist in his work. [R. H. Robins, General

Linguistics ix (1964), p. 355]

(c)

corpus data

The

theoretical objection one may make against the ‘corpus’ method is that two

investigators operating on the same language but starting from different

‘corpuses’ [note: the usual plural is ‘corpora’], may arrive at different

descriptions of the same language. [E. Palmer (tr.) Martinet’s Elementary

General Linguistics ii (1964), p. 40]

PROBLEMS:

a lot of work; must be large; unavailability of (eg personal) data;

‘errors’ of usage

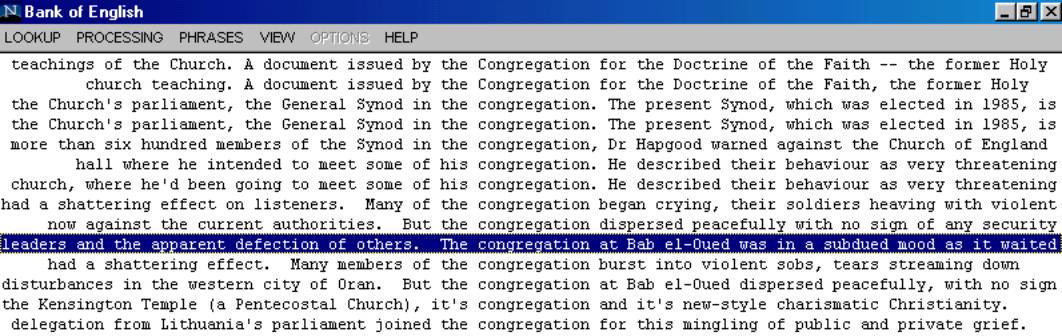

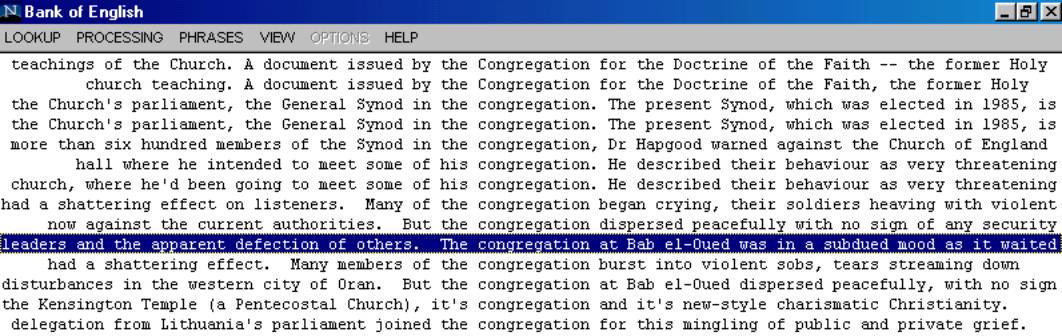

Collins

Cobuild Dictionary is, for example, is based on a corpus of the English

language called ‘The Bank of English’ (http://titania.cobuild.collins.co.uk).

It is possible to search the corpus (using, for example, its concordancing tool).

For

example, we might be interested if the word congregation takes on a

singular or plural verb form. If I search one part of the corpus, I might see

the following.

Obviously, many of the citations are not useful because congregation

does not occur as subject or if it does, the verb is in the past tense form

that does not make number distinctions. Only the highlighted example

shows the use of the singular verb form was. What I will need to do is

examine more parts of the corpus to see if it is indeed the case that congregation

always takes a singular verb form.

4. The noun phrase

A

noun phrase or NP is a phrase that has a noun as its head.

the

cat with black stripes

traditional

(non-linguistic) definition: name of a person, place or thing

RULE

OF THUMB: they can often be modified by determiners (like a, the, my, some)

before them

formal

criteria?

variation in the NP

|

(a) She pushed a door open. |

Std E (count noun; any door) |

|

(b) She pushed the door open. |

Std E (count noun; a particular door) |

|

(c) She pushed door open. |

Colloq. Singaporean English |

|

|

|

|

(a) Chocolate is nice. |

Std E (non-count; ‘chocolate’ in general) |

|

(b) The chocolate is nice. |

Std E (non-count; definite) |

|

(c) A chocolate is nice. |

Informal (ellipsis)? |

|

|

|

|

(a) He’s in hospital again. |

BrE (= he’s been hospitalised, warded [SgE]) |

|

(b) He’s in the hospital again. |

BrE (eg visiting); AmE, Scottish E |

|

|

|

|

(a) I will be in the bank. |

Std E |

|

(b) I will be in bank. |

Some African varieties; CSE |

quick

‘grammar’ of how and when a(n) and the is used in English?

[determiners]

Pronouns

A pronoun is a word that

stands for (pro-), or refers to, a noun

A first-person pronoun refers to the speaker(s)

A second-person pronoun refers to the person or people being addressed

A third-person pronoun refers to a third party, usually not in the vicinity.

|

|

|

Tyneside non-standard |

|

Standard |

||

|

Person |

|

Subject |

Non-subject |

|

Subject |

Non-subject |

|

Singular |

1st |

I |

us |

|

I |

me |

|

|

2nd |

ye |

you |

|

you |

you |

|

|

3rd |

she |

her |

|

she |

her |

|

|

|

he |

him |

|

he |

him |

|

|

|

it |

it |

|

it |

it |

|

Plural |

1st |

us |

we |

|

we |

us |

|

|

2nd |

yous |

yous/yees |

|

you |

you |

|

|

3rd |

they |

them |

|

they |

them |

Distinctions

of person, number (singular or plural) and case (subject, non-subject, etc.).

Tyneside English:

Give

us a kiss then.

Us’ll do it.

They beat we four–nil.

Use

of the second-person pronoun:

(The

novel is set in the 1920s in the English Midlands, and Mellors the game-keeper

is talking to Lady Constance Chatterley.)

He tramped with a quiet inevitability over the brick floor, putting food

for the dog in a brown bowl. The spaniel looked up at him anxiously.

‘Ay,

this is thy supper, tha nedna look as if tha wouldna get

it!’ he said.

He

set the bowl on the stairfoot mat, and sat himself on a chair by the wall, to

take off his leggings and boots. The dog instead of eating, came to him again,

and sat looking up at him, troubled.

He

slowly unbuckled his leggings. The dog edged a little nearer.

‘What’s

amiss wi’ thee then? Art upset because there’s somebody else here? Tha’rt

a female, tha art! Go an’ eat thy supper.’

He

put his hand on her head, and the bitch leaned her head sideways against him.

He slowly, softly pulled the long silky ear.

‘There!’

he said. ‘There! Go an’ eat thy supper! Go!’

He

tilted his chair towards the pot on the mat, and the dog meekly went, and fell

to eating.

‘Do

you like dogs?’ Connie asked him.

[D

H Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1944), Ch. 14]

5.

The verb phrase

A

verb phrase is a phrase where the head is a verb.

main

verb v auxiliary verbs

traditional

(non-linguistic) definition is that a verb is a ‘doing’ or ‘action’ word

formal

criteria: in contemporary Standard English can take four forms: the base form (eg

looked), the -s form (looks), the –ed form (looked)

and the –ing form (looking).

Verb

inflexions

Compare the following verb forms used with different pronouns.

|

South-west England |

East Anglia/SCE |

Standard English |

archaic |

|

I loves |

I love |

I love |

|

|

you loves |

you love |

you love |

thou lovest, ye love |

|

she loves |

she love |

she loves |

she loveth |

|

he loves |

he love |

he loves |

he loveth |

|

it loves |

it love |

it loves |

it loveth |

|

we loves |

we love |

we love |

|

|

they loves |

they love |

they love |

|

agreement

word endings

inflexions (inflections)

Tense

and aspect

Tense

is a category in grammar that can be seen in the verb form (inflexion) chosen;

it is used to locate an event or situation in time — linguists describe English

as having two tenses: past and non-past (eg ‘walked’ v. ‘walk/s’).

Aspect

is another term frequently used in relation to the verb phrase. It is a

grammatical category that has to do with the meaning of the verb in relation to

time. Aspect provides information such as whether an event or situation is

continuing or completed; or whether it’s a one-off event as opposed to one that

is habitual, or repeated. Standard English has two aspects: the perfective (eg

‘I have walked a mile’) and the progressive (eg ‘I am walking home’;

this is sometimes called ‘continuous’). The two aspects can also be combined (eg

‘I have been walking home’).

Restriction

of progressive for verbs not of ‘limited duration’

? My grandfather was

having two wives.

? My mother is having

a terrible headache.

He is swimming now.

Notion

of ‘completion’ (perfective aspect)

He has swum the

Johore Straits.

1 (a) I walk a mile. [n-pa]

(b) I walked a mile. [pa]

(c) I have walked a mile. [n-pa, perf]

(d) I had walked a mile. [pa, perf]

(e) I am walking a mile. [n-pa, prog]

(f) I was walking a mile. [pa, prog]

2

(a) I have chicken pox.

(b) I had chicken pox.

(c) I have had chicken pox.

(d) I am having chicken pox.

Sentences 3 and 4 are not available in Standard English, but are

possible in colloquial Singaporean and Malaysian English. This is understandable

if we also look at sentences 5 and 6. In Malay and Hokkien, the two languages

that have had strong influence on colloquial Singaporean and Malaysian English,

the notion of completion is expressed by the addition of the words sudah

and liáu (cf. Mandarin le), both of which mean ‘already’. It is

therefore not surprising that sentences 3 and 4 are available for expressing

completion in this variety of English.

1 I have eaten.

2 I have eaten already.

3 I eat already.

4 I already eat.

5 (a) Saya sudah makan. [Malay]

(b) I already eat. [literal translation]

6 (a) Goá chiåh pá liáu. [Hokkien Chinese]

[á = upper tone; å = lower entering tone]

(b) I eat full already. [literal translation]

QUICK QUIZ/DISCUSSION

Which of the following are clauses?

1. The man who chased me

2. Rojak is shiok

3. (Are you tired?) I am, rather.

Discuss

these sentences: what do they mean? are they say-able?

1. I

like nasi lemak.

2. I

like the nasi lemak.

3. I

would like a nasi lemak.

4. I

want four nasi lemaks please.

5. I

have information for you.

6. I

have an information for you.

7. I

have two informations for you.

GO to Part 2

BACK to contents page

© Peter Tan 2001