Wednesday, 1-viii-2001, 18:44 GMT 19:44 UK

Wednesday, 1-viii-2001, 18:44 GMT 19:44 UK

Azerbaijan

says it in Latin

For

the third time in a century, the people of

From 1 August,

the Cyrillic alphabet, which was imposed by Stalin in 1939, is being dumped in

favour of Latin script, used throughout the Western world.

The move

was finally decreed in June by

It should

be no problem for

But it’s

the older generations who will have the most headaches over the change.

Anyone who

was educated in Azeri Cyrillic, in other words anyone over the age of 26, will

have woken up to find the whole appearance of their visual world dramatically

changed.

All

business and official documents have to be written in Latin script. Workers are

out in the capital,

Advertisements,

magazines and newspapers are also due to make the change. In the longer term,

textbooks, dictionaries and other literature will also have to appear in the

Latin script, which is a massive financial undertaking for the republic.

Critics of

the switch fear it will marginalise Russian speakers, leaving them and the

older generation isolated.

The biggest

complainers are the newspapers. Up until this summer they were a strange

mish-mash of Latin and Cyrillic scripts, with headlines in Latin script and the

actual article in Cyrillic.

The editors

thought their readers would find it too difficult to read a whole article in

the Latin script.

One paper –

Yeddi Gun, or Seven Days – took the radical step of becoming a Russian-language

publication instead of changing to the Latin script.

Other independent

newspapers welcomed the move in principle, but some editors sent a letter to

the prime minister saying they feared it would probably lead to many papers

closing down.

The editors

think many of their readers will not be comfortable with the new script and

could turn their backs on newspapers altogether.

The fate of

one paper, Ayna or Mirror, would seem to bear this out. It made the switch to

Latin script several months ago and now lies mostly unread on newspaper stands.

The

government is trying to provide a helping hand. It has set up an official web

site to help simplify the switch and provide the Azerbaijani alphabet in Latin

script for use on computers and keyboard layouts.

The snag is

it currently operates in Russian only, though an Azeri version is due to appear

soon.

In

the meantime, everyday life goes on. But some things will take slightly longer:

when a state employee, such as the gasman, comes to call, householders will now

have to wait while the official laboriously writes his name in Latin script.

For

more information about the Azeri language and culture, go to http://azeri.org or http://www.azer.com.

LATIN

ALPHABET

upper

case:

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

lower

case:

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

CYRILLIC

ALPHABET

upper

case

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Ъ Ы Ь Э Ю Я

lower

case

а б в г д е ж з и й к л м н о п р с т у ф х ц ч ш щ ъ ы ь э ю я

If

anyone wants to pursue the issue a little further, there is an article in the

Workbin:

Lynley

Hatcher (2008), ‘Script change in Azerbaijan: acts of identity’, International Journal of the Sociology of

Language 192, 105-116.

In

the article, Hatcher outlines the three major script changes to the Azeri

language in the twentieth century: traditional Arabic, then Latin, then

Cyrillic and then back to Latin. She suggests that these changes signalled a

changed allegiance, sometimes voluntary and sometimes changed.

She

draws on the notion of ‘acts of identity’ from the work of Le Page and

Tabouret-Keller (1985): speakers make linguistic choices and through that

perform acts of identity and project the identity they want to claim for

themselves.

The

Arabic alphabet indexes Azerbaijan’s identity being rooted in the Muslim world.

Its neighbour Iran also used the Arabic script.

After

being incorporated into the USSR in 1920, the Soviets initiated a shift to

Latin in a bid to divide the nation from Iran and its Muslim roots.

In

the 1930s, the Soviets became draconian in their approach and in 1939, Stalin

announced that Cyrillic would be used for Turkic languages. This was part of

the enterprise of Russification and of isolation between Turkic nations.

After

independence in 1991, there were various groups proposing different scripts.

The Latin script favoured a more Turkish identity. This was a painful process

for writers:

Within five years or so, the younger

generation won’t be able to read my books. Sometimes I think: ‘What a pity”

I’ve been serving this society as a scholar for 55 years. But none of my books

will even be readable in the future.’ I’m still convinced, however, that we

made the right decision to embrace Latin. Our future is the main issue … I’m

among the happiest people in the world because I’ve seen the collapse of the

Soviet Union … It’s important for us to adopt the Latin alphabet. (Kamal Talibzade 2000: 66)

Kazakhstan to Qazaqstan: Why would a

country switch its alphabet?

31 October 2017

The Kazakh language has long been unsure which alphabet to find a

comfortable home in and it's now in for another transition - but this is not without

controversy.

Last Friday Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev finally decreed

that the language would shed its heavy Cyrillic coat and don what he hopes to

be a more fashionable attire: the Latin alphabet.

Is

this going to be easy?

No. The Latin alphabet has far fewer

letters: There will need to be creative

combinations with apostrophes to catch all the sounds needed for the Kazakh

language.

Kazakhstan

is in an unusual position: None of

the alphabets that exist seem like a perfect fit or have a long enough tradition

to be the uncontested host for its language.

Kazakh

is a Turk-based language and its history is political: Originally it was written in Arabic. Enter the Soviet Union who in

1929 did away with Arabic and introduced Latin - only to 11 years later shift

to the Cyrillic alphabet to have the republic more in line with the rest of the

USSR.

The Kazakh version of Cyrillic has

33 Russian letters and nine Kazakh ones, while the Latin script only has 26.

The big changeover is to be official

by 2025.

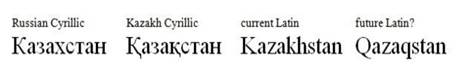

Confused

by all this talk about letters and characters? Before you get lost in translation, here are a few spellings of the

country's name just to give you an idea:

So

why change?

President

Nursultan Nazarbayev has given a lengthy explanation: There are many reasons like of

modernising Kazakhstan, but also determined by "specific political reasons".

Political pundits see it as step to weaken the historical ties to Russia: Shedding not only the Russian alphabet, the thinking goes, but also the influence Moscow still likes to exert over its post-Soviet backyard in central Asia.ght soon need a new sign for that table

Of the other four Former Soviet Republics

in Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan still use Cyrillic while Uzbekistan

and Turkmenistan are using the Latin alphabet.

Will it be a smooth transition?

This

discussion is not new: The change

to the Latin alphabet has been mooted several times since the country's independence

after the end of the Soviet Union, but so far has failed to garner widespread

support.

Because: If even the name of the country would change from Kazakhstan to Qazaqstan,

just imagine the potential for confusion in people's daily lives?

Let's

look at the innocent carrot for an example: The Kazakh word for carrot is

‘сәбіз’ and would traditionally be spelled

‘sabeez’ in Latin. In new Latin alphabet though, it will end up as ‘sa'biz’.

This, again, is awfully close to the Latin spelling of

an extremely rude Russian swear word.

Not all the mix-ups are as delicate

as this one: But there's ample

discussion online of people confused and amused by how they now should write

their own names and whether the change will work out well nor not.

While some see it as a right step

out of the shadows of the Soviet past and of present Russian influence, others warn

it's a politically motivated move which will disconnect future generations from

the country's written past century.

So what is next?

By the end of the year there will

a finalised official Latin spelling. By next year teacher training is to begin and

new textbooks will be developed.

Come 2025, all official paperwork

and publications in the Kazakh language will be in the new Latin script.

President Nazarbayev indicated though there would be a transition period where

Cyrillic might still be used as well.

Given

that Russian is the country's second official language, signs and official

documents will though remain bilingual: in the Kazakh with Latin letters and in

Russian with the Cyrillic alphabet.

LATIN

ALPHABET

upper

case:

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

lower

case:

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

CYRILLIC

ALPHABET

upper

case

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Ъ Ы Ь Э Ю Я

lower

case

а б в г д е ж з и й к л м н о п р с т у ф х ц ч ш щ ъ ы ь э ю я

If

anyone wants to pursue the issue a little further, there is an article in the

Workbin:

Lynley

Hatcher (2008), ‘Script change in Azerbaijan: acts of identity’, International Journal of the Sociology of

Language 192, 105-116.

In

the article, Hatcher outlines the three major script changes to the Azeri language

in the twentieth century: traditional Arabic, then Latin, then Cyrillic and

then back to Latin. She suggests that these changes signalled a changed

allegiance, sometimes voluntary and sometimes changed.

She

draws on the notion of ‘acts of identity’ from the work of Le Page and

Tabouret-Keller (1985): speakers make linguistic choices and through that

perform acts of identity and project the identity they want to claim for

themselves.

The

Arabic alphabet indexes Azerbaijan’s identity being rooted in the Muslim world.

Its neighbour Iran also used the Arabic script.

After

being incorporated into the USSR in 1920, the Soviets initiated a shift to

Latin in a bid to divide the nation from Iran and its Muslim roots.

In

the 1930s, the Soviets became draconian in their approach and in 1939, Stalin

announced that Cyrillic would be used for Turkic languages. This was part of

the enterprise of Russification and of isolation between Turkic nations.

After

independence in 1991, there were various groups proposing different scripts.

The Latin script favoured a more Turkish identity. This was a painful process

for writers:

Within five years or so, the younger

generation won’t be able to read my books. Sometimes I think: ‘What a pity”

I’ve been serving this society as a scholar for 55 years. But none of my books

will even be readable in the future.’ I’m still convinced, however, that we

made the right decision to embrace Latin. Our future is the main issue … I’m

among the happiest people in the world because I’ve seen the collapse of the

Soviet Union … It’s important for us to adopt the Latin alphabet. (Kamal Talibzade 2000: 66)