Two articles on Nostratic from the New York Times

1. Linguists Debating Deepest Roots of Language (27-6-1995)

2. What We All Spoke When the World was Young (1-2-2000)

Copyright 1995 The New York Times

27 June, 1995, Tuesday, Late Edition - Final

Section C; Page 1; Column 4; Science Desk

2309 words

Linguists Debating Deepest Roots of Language

IN their archaeological

digs through the strata of human language, linguists have long been fascinated

by the seeming similarities between the English words ‘fist’, ‘finger’ and

‘five’. The motif is repeated by the Dutch, who say ‘vuist’, ‘vinger’ and

‘vijf’, and the Germans, who say ‘faust’, ‘finger’ and ‘fünf’. Traces of the

pattern can even be found as far away as the Slavic languages like Russian.

Conceivably, sometime in

the distant past, before these languages split from the mother tongue, there

was a close connection among the words for a hand and its fingers and the

number five. But did the mathematical abstraction come from the word for fist,

or, as some linguists have proposed, was it the other way around? The answer

could provide a window into the development of the ancient mind.

In a paper now being

prepared for publication in a book next year, Dr Alexis Manaster Ramer, a

linguist at Wayne State University in Detroit, argues that the mystery may now

be solved: fist came before five. But more important than his conclusion is the

method by which it was derived.

It is widely accepted that

English, Dutch, German and Russian are each branches of the vast Indo-European

language family, which includes the Germanic, Slavic, Romance, Celtic, Baltic,

Indo-Iranian and other languages – all descendants of more ancient languages

like Greek, Latin and Sanskrit. Digging down another level, linguists have

reconstructed the even earlier tongue from which all these languages are

descended. They call it proto-Indo-European, or PIE for short.

But in a move sure to be

hotly disputed by mainstream linguists, Dr Manaster Ramer contends that to find

the root of the fist-five connection one must look beyond the Indo-European

family and examine two separate language groups: Uralic, which includes

Finnish, Estonian and Hungarian, and Altaic, said to include Turkish and

Mongolian languages. All three families, he contends, contain echoes of a lost

ancient language called Nostratic.

If Dr Manaster Ramer is right,

his discovery will provide ammunition for a small group of linguists who make

the controversial claim that Indo-European, Uralic, Altaic and other language

families like Afro-Asiatic, which includes Arabic and Hebrew, the Kartvelian

languages of the South Caucasus and the Dravidian languages concentrated in

southern India, all are descendants of Nostratic, which was spoken more than

12,000 years ago.

Most language experts

remain highly sceptical of the Nostratic hypothesis, which enjoyed so much

publicity in the late 1980s and early 1990s that it is sometimes described as

the linguists’ version of cold fusion. ‘It would be terrific if it’s true, but

we don’t want to jump to conclusions,’ said Dr Brian Joseph, a linguist at Ohio

State University in Columbus. Dr Joseph and Dr Joe Salmons of Purdue University

in West Lafayette, Indiana, are editing the book, Nostratic: Evidence and

Status (John Benjamins), in which the analysis of the five-fist connection

will appear.

But Dr Joseph believes that

while the Nostratic debate remains as heated as ever, it has reached a higher

level of sophistication, with both sides offering more precise arguments and

careful scholarship. ‘Mainstream linguists who in the past had dismissed

Nostratic are now willing to examine it on an objective and scientific basis,’

he said. While he and Dr Salmons both count themselves as sceptics, they hope

their book will be a milestone in linguistic scholarship. ‘Even if the more

mainstream linguists decide to reject Nostratic,’ Dr Joseph said, ‘at least the

evidence will be laid out in a fair and balanced way.’

It is not that most

linguists find implausible the idea that all languages may ultimately have

derived from an ancient ur-language spoken millenniums ago. After all, analysis

of mitochondrial DNA from the cells of various ethnic groups strongly supports

the notion that all humans come from the same genetic stock. If this small

group of original humans spoke a single language, then all present-day

languages are descended from it. The hypothetical Nostratic is not the

ur-language but might be one of its major branches. However, critics of the

Nostratic hypothesis have long argued that it is unprovable – any similarities

between languages as distant as the Altaic and Indo-European would have been

washed out long ago. They dismiss the parallels unearthed by the Nostraticists

as coincidences.

As recently as the early

1990s, most evidence for an ancient language relied on work done in the 1960s

by Soviet scholars, who popularised the word Nostratic, meaning ‘our

language’. But now a second wave of research is revitalising the field.

Veterans of the Nostratic programme like Dr Vitaly Shevoroshkin of the

University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and Dr Aaron Dogopolsky of the University

of Haifa in Israel continue to come up with new evidence, as do younger

scholars like Dr Manaster Ramer.

In a book published last

year, The Nostratic Macrofamily: A Study in Distant Linguistic Relationship

(Mouton de Gruyter), two independent scholars, Allan Bomhard and John Kerns,

compiled some 600 Nostratic roots with counterparts (what the linguists call

cognates) in languages said to be descended from Nostratic. On another front,

Dr Joseph Greenberg, a retired Stanford University linguist, is in the midst of

a two-volume study of his own version of the Nostratic hypothesis: Indo-European

and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family. Dr Greenberg’s

Eurasiatic overlaps with Nostratic but also includes other languages like

Japanese and Eskimo-Aleut.

In an unpublished

manuscript of yet another forthcoming book, ‘Indo-European and the Nostratic

Hypothesis’, Mr Bomhard concludes that the evidence for the common ancestral

language is ‘massive and persuasive’. ‘As the 20th century draws to a close, it

is simply no longer reasonable to hold to the view that Indo-European is a

language isolate,’ he writes. ‘Indo-European has relatives and these must now

be taken into consideration.’

One of the most vehement

critics of Nostratic, Dr Donald Ringe, a linguist at the University of

Pennsylvania, recently surprised himself by finding statistical evidence that

resemblances between Uralic and Indo-European may indeed be due to more than

chance. Dr Ringe expected his analysis, which will also be published in the

book edited by Dr Joseph and Dr Salmon, to undermine the Nostratic hypothesis.

But Dr Ringe is quick to

point out that a connection between Indo-European and the Uralic languages like

Hungarian and Finnish is the least controversial claim of the Nostraticists. He

remains as dubious as ever that statistically significant connections can be

found between Indo-European and more distant languages.

In a paper called ‘

“Nostratic” and the Factor of Chance,’ published in the current issue of the

journal Diachronica, Dr Ringe examined a list of 205 cognates that the

Russian linguist Vladislav Illich-Svitych found among six language families

commonly said to have descended from Nostratic. He concluded that the

similarities are indistinguishable from those that would have arisen by chance.

As a test of his analytical technique, Dr Ringe applied the same method to two

Indo-European languages, which are known to be related, and found that the

similarities there are indeed statistically significant.

‘It is time to tighten up standards

of evidence in historical linguistics,’ he concluded in his paper. ‘If we

enforce rigour, the truth will enforce itself.’

But some linguists believe

Dr Ringe is misinterpreting his own statistics. Dr Manaster Ramer argues that

Dr Ringe, who has accused the Nostraticists of ‘innumeracy,’ is himself

engaging in ‘pseudomathematics’.

‘To use mathematics in any

science, including linguistics, you have to understand the meaning of the

mathematics and not just learn to manipulate formulas,’ he said. Dr Manaster

Ramer believes that the probability distribution that Dr Ringe found for

Nostratic is exactly what would be expected in languages that split apart long

ago and developed independently. The true test of whether languages are related

is not statistical comparisons, he insists, but the tools of historical

linguistic analysis. If one can find answers in Uralic and Altaic to puzzles in

Indo-European, like the five-fist connection, he says, that strengthens the

argument for an ancestral Nostratic tongue.

Historical linguists start

with two languages they suspect are related, then search for potential cognates

– words like the Italian ‘luce’ (‘light’) and ‘pace’ (‘peace’), which appear in

Spanish as ‘luz’ and ‘paz’. Then, by deriving rules for how sounds mutate over

time, they try to reconstruct the ancient roots.

In actual practice, the

correspondences between related words are usually far more convoluted and

opaque to superficial examination. English and Armenian both are believed to

descend from proto-Indo-European. But it takes a great deal of linguistic

manipulation to show how the Armenian word for two, ‘erku’, is related to its

English counterpart. To add to the confusion, words that seem similar can turn

out to be unrelated. Linguists consider it coincidental that the German word

for ‘awl’ happens to be ‘ahle’, or that the Aztec word for ‘well’ is ‘huel’.

For that matter, the English word ‘ear’, referring to the fleshy flaps on

either side of the head, has been found to be historically unrelated to an

‘ear’ of corn.

There are other mirages

that can create the illusion of a deep historical wellspring. Baby words like

‘papa’ and ‘mama’ are common across languages probably because the labial

consonants – those made with the lips – are among the first that children

learn. Onomatopoeic words like ‘clash’ or ‘meow’ also tend to turn up

independently in unrelated languages. And of course languages borrow words from

one another all the time. A Japanese office worker can log off her ‘konpyuutaa’

and head for ‘Makudonarudo’ to grab a ‘hanbaagaa’ and a steaming cup of ‘hotto

kohii’ for lunch.

To avoid being misled by

such specious similarities, linguists try to concentrate on basic words –

numbers, parts of the body – likely to have been embedded in a language from

the start. As reconstructed by linguistic archaeologists, the ancient

Indo-European word for five was ‘penkwe’, which became ‘pente’ in Greek,

‘quinque’ in Latin and ‘panca’ in Sanskrit. One can immediately see surface

similarities between ‘penkwe’ and the Indo-European roots for fist, ‘pnkwstis’

and finger ‘penkweros’. But though the resonances ring, the source of the

connection has remained obscure.

Finding few clues within

Indo-European itself, Dr Manaster Ramer looked farther afield. Linguists examining

Finnish, Hungarian and Estonian had reconstructed an ancient Uralic root,

‘peyngo’, meaning fist or palm of the hand. And from Turkish, Mongolian and

related languages, linguists had reconstructed the corresponding word in

Altaic: ‘p’aynga’. (The accent is a sign that there were two different p sounds

in the language.)

Working backward from

Uralic and Altaic, Dr Manaster Ramer reconstructed a hypothetical Nostratic

antecedent, ‘payngo’. Then, using what he believed to be the rules by which

Nostratic mutated into proto-Indo-European, he showed how the Nostratic word

for fist could have spawned the Indo-European word for five.

In another attempt to show

that the Indo-European languages descended from Nostratic, Dr Manaster Ramer

analysed the word ‘stink’, which came into English from the hypothetical

Germanic root stinkwan. Linguists find this word interesting because it

appears to have no counterparts in other Indo-European languages. Dr Manaster

Ramer argues that it could have derived from a hypothetical Nostratic word,

‘stunga’.

In his own work, Mr Bomhard

points to evidence that the first-person pronoun ‘me’ and variations like ‘mi’,

‘ma’, ‘mo’ and ‘mea’ appear in PIE and in the reconstructed protolanguages

Kartvelian, Afro-Asiatic, Uralic, Altaic and the extinct language Sumerian. Mr

Bomhard believes that ancestral Indo-Europeans said ‘bor’ for ‘to bore’ or ‘to

pierce’; the Afro-Asiatics said ‘bar’, the Altaics said ‘bur’, the Sumerians

‘bur’, and the Dravidians ‘pur’, while the Uralics said ‘pura’ for borer or

auger. And while Indo-Europeans said ‘pes’ or ‘pos’ for penis, speakers of

Altaic said ‘pusu’ for ‘to squirt out’ or ‘to pour’ and the Sumerians said

‘pes’ not only for sperm and semen but also for descendant, offspring and son.

Most linguists are leery of

reading too much significance into reconstructions that are based on

reconstructions. Are the Nostraticists excavating into the past or building a

house of cards?

‘The bottom line is that

the evidence isn’t good enough,’ Dr Ringe said. ‘In particular, neither

Manaster Ramer nor anyone else has demonstrated that the similarities they’ve

found between the various recognised language families are due to anything

other than chance.’

With such different ideas about

how Nostratic scholarship should proceed, it is unlikely that either Dr Ringe

or Dr Manaster Ramer will come around to the other’s point of view. In the

meantime, linguists watching from the sidelines say there is a huge amount of

work to be done before Nostratic can confidently be verified or rejected.

‘I think there is a new

appreciation of the level of sophistication one needs to approach the problem,’

said Dr Brent Vine, a Princeton University classicist. ‘So much is now known

about all the different language families involved that no one person can

seriously claim to have the kind of control needed for Nostratic research. What

is really needed is a team effort.’

GRAPHIC: Chart: ‘Say What?’

The six language families

shown as branches on this tree are believed to have originated in the Nostratic

language (tree trunk), one of several major branches of a single hypothetical

ancient ‘mother tongue’ from which all languages are believed to be derived.

Map/Diagram: ‘Modern

Children of Nostratic?’

One scheme of current

language group distribution. (Source: Scientific American)

Copyright

2000 New York Times

1

February 2000

SCIENTIST AT WORK / Joseph H. Greenberg

What We All Spoke When the World Was Young

By

NICHOLAS WADE

In the beginning, there was one people, perhaps no more than 2,000

strong, who had acquired an amazing gift, the faculty for complex language.

Favoured by the blessings of speech, their numbers grew, and from their

cradle in the northeast of Africa, they spread far and wide throughout the

continent. One small band, expert in the making of boats, sailed to Asia, where

some of their descendants turned westward, ousting the Neanderthal people of

Europe and others

east toward Siberia and the Americas.

These epic explorations began some 50,000 years ago and by the time the

whole world was occupied, the one people had become many. Differing in creed,

culture and even appearance, because their hair and skin had adapted to the

world’s many climates in which they now lived, they no longer recognized one

another as the children of one family. Speaking 5,000 languages, they had long

forgotten the ancient mother tongue that had both united and yet dispersed this

little band of cousins to the four corners of the earth.

|

|

|

|

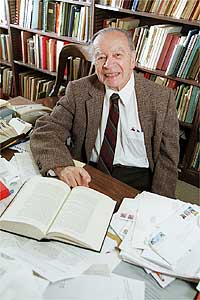

Dr Greenberg has grouped most of the world’s

languages into a small number of clusters based on their similarities. |

So

might read one possible account of human origins as implied by the new evidence

from population genetics and archaeology. But the implication that all languages

are branches of a single tree is a subject on which linguists appear strangely

tongue-tied.

Many

deride attempts to reconstruct the family tree of languages beyond the most

obvious groupings like the Romance languages and Indo-European. Their argument

is that language changes too fast for its roots to be traced back further than

a few thousand years. If any single language ever existed, most linguists say,

it is irretrievably lost.

But

one scholar in particular, Dr Joseph H. Greenberg of Stanford University, has

defied this ardent pessimism. In the course of a long career, he has classified

most of the world’s languages into just a handful of major groups.

Though

it remains unclear how these superfamilies may be related to one another, he

has identified words and concepts that seem common to them all and could be

echoes of a mother tongue.

And

this month, at the age of 84, Dr Greenberg is publishing the first of two

volumes on Eurasiatic, his proposed superfamily that includes a swath of

languages spoken from Portugal to Japan.

Like

the biologist E. O. Wilson, Dr Greenberg is that rare breed of academic, a

synthesiser who derives patterns from the work of many specialists, an exercise

the specialists do not always welcome.

But

though biologists came to acknowledge the pioneering value of Dr Wilson’s work,

linguists have reached no such consensus on that of Dr Greenberg.

Will

he one day be recognised as having done for language what Linnaeus did for

biology, as his Stanford colleague and associate Dr Merritt Ruhlen believes, or

is his work more fit, as one critic has urged, to be ‘shouted down’?

Dr

Greenberg is by no means an outcast from his profession. He is one of the very

few linguists who are members of the National Academy of Sciences, the

country’s most exclusive scientific club. His work on language typology

(universal patterns of word order) is highly regarded. Somewhat puzzlingly, his

fellow linguists generally accept his work on the relationships among African

languages but furiously dispute his ordering of American Indian languages, even

though both classifications were achieved with the same method.

Dr

Greenberg’s work is of considerable interest to population geneticists trying

to reconstruct the path of early human migrations by means of genetic

patterning in different peoples.

Although

genes and languages are not bequeathed in the same way, both proceed in a

series of population splits.

‘We

have found a lot of significant correspondences between what he says and what

we see genetically,’ said Dr Luca Cavalli-Sforza, a leading population

geneticist at Stanford. In his view, the majority of linguists are not

interested in the evolution of language. They ‘have attacked Greenberg cruelly,

and I think frankly there is some jealousy behind it because he has been so

successful,’ Dr Cavalli-Sforza said.

In

a windowless office lined with grammars and dictionaries of languages from all

over the world, Joseph Greenberg fishes in the plastic shopping bag that is

serving as his briefcase. He pulls out one of the handwritten notebooks that

are the key to his method of discovering language relationships. Down the left

hand margin is a list of the languages being compared. Along the top are names

of the vocabulary words likely to yield similarities.

His

method, which he calls mass or multilateral comparison, is to compare many

languages simultaneously on the basis of 300 core words in the hope that they

will sort themselves into clusters representative of their historical

development. Many linguists believe such an exercise is futile because words

change too quickly to preserve any ancestry older than 5,000 years or so.

‘They

sell their own subject short,’ Dr Greenberg says. ‘Certain items in language

are extremely stable, like personal pronouns or parts of the human body.’

Born

in Brooklyn in 1915, he was interested in language almost from birth. His

father spoke Yiddish and his mother’s family German. ‘I was brought up to

believe Yiddish was an inferior language because my father’s relatives got

invited to the house as seldom as possible,’ he said. Hebrew school exposed him

to a fourth language. He had a good enough ear that an alternative career as a

professional pianist beckoned.

But

anthropology won out. After doctoral studies at Northwestern, he did fieldwork

on the pagan cults of the Hausa-speaking people of northern Nigeria before

deciding that his true interest lay in linguistics.

At

the time, there was no agreement on the history of African languages. ‘So I

started in a simple-minded way,’ Dr Greenberg said. ‘I took common words in a

number of languages and saw if the languages fell into groups.’ He found that

he could reduce all the continent’s languages first to 14 and later to 4 major

clusters.

In

a 1955 article, he described these as Afro-Asiatic, which includes the Semitic

languages of Arabic and Hebrew, as well as ancient Egyptian, and is spread

across Northern Africa; Nilo-Saharan, a group of languages spoken in Central

Africa and the Sudan; Khoisan, which includes the click languages of the south;

and Niger-Kordofanian, a superfamily that includes everything in between,

including the pervasive Bantu languages.

After

a decade of controversy, Dr Greenberg’s African classification became widely accepted.

‘But then a lot of people said I had gotten the correct results with the wrong

method,’ he said.

Method

is the formal issue that divides Dr Greenberg from his critics. They say that

the only way to prove that a group of languages is related is by establishing

regular rules governing how words change as one language morphs into another.

The

‘p’ sounds in ancestral Indo-European, for example, change predictably into ‘f’

in German and English. Mere similarities between the words in different languages,

like those on which Dr Greenberg relies, fall far short of proof, his critics

say, because the similarities could arise from chance or borrowing.

Because

of the looseness of sound and meaning that Dr Greenberg allows in claiming

similarities, his data ‘do not rise above the level of chance,’ said Dr Sarah

Thomason, a linguist at the University of Michigan.

Dr

Brian D. Joseph of Ohio State University, who studies Nostratic, a proposed

language superfamily similar to Euroasiatic, described Dr Greenberg as ‘a

romantic’ for believing his methods could retrieve long lost languages.

Dr

Lyle Campbell, of the University of Canterbury in New Zealand and the author of

a textbook on historical linguistics, said that rigorous proof was necessary

because languages changed so fast, and that Dr Greenberg’s methods were

‘woefully inadequate’.

To

Dr Greenberg and his colleague Dr Ruhlen, the critics’ requirement for

establishing regular rules of sound change defies both common sense and

history. The sound regularities in Indo-European, they say, were not detected

until after the languages had been grouped by inductive methods similar to Dr

Greenberg’s. The insistence on demonstrating sound-change regularities, in

their view, has thwarted any further reconstruction of language families.

‘It’s

a misguided perfectionism that is so perfect they have had no result,’ Dr

Ruhlen said. His and Dr Greenberg’s aim is to establish the probable links from

which the full history of human language can be inferred.

‘The

ultimate goal,’ Dr Greenberg said in concluding his 1987 book Language in

the Americas (Stanford University Press), ‘is a comprehensive

classification of what is very likely a single language family. The

implications of such a classification for the origin and history of our species

would, of course, be very great.’

Because

the Americas have been inhabited only recently, at least as compared with

Africa, it would be surprising to find a larger number of language groups, and

Dr Greenberg decided there were only three, even though other linguists posit

100 or so independent stocks.

Amerind

is the vast superfamily to which, in his view, most native languages of North

and South America belong.

The

other two clusters are Na-Dene, a group of languages spoken mostly in Alaska

and northeast Canada, and Eskimo-Aleut, spoken across northern Alaska and

Canada.

One

striking feature that unites the Amerindian languages of both Americas, in Dr

Greenberg’s view, is the use of words starting in ‘n’ to mean I/mine/we/ours

and words beginning in ‘m’ to mean thou/thine/you/ yours. Not every language

shows this pattern, but almost every Amerindian language family has one or more

languages that have it, suggesting that all are derived from an original

language in which first and second person pronouns started this way.

In

the course of classifying the languages of the Americas, Dr Greenberg realised

that their major families were related to languages on the Eurasian continent,

as would be expected if the Americas had been inhabited by people migrating

through Siberia. Na-Dene, for example, is related to an isolated Siberian

language known as Ket.

To

help with the American classification, Dr Greenberg started making lists of

words in languages of the Eurasian land mass, particularly personal pronouns

and interrogative pronouns.

‘I

began to see when I lined these up that there is a whole group of languages

through northern Asia. I must have noticed this 20 years ago. But I realised

what scorn the idea would provoke and put off detailed study of it until I had

finished the American languages book,’ he said.

Thirteen

years later, Dr Greenberg has now classified most of the languages of Europe

and Asia into the superfamily he calls Eurasiatic. Its seven living components

are Indo-European (examples are English, Russian, Greek, Iranian, Hindi);

Uralic (Hungarian, Finnish); Altaic (Turkish, Mongolian); the

Korean-Japanese-Ainu group; Eskimo-Aleut; and two Siberian families known as

Gilyak and Chukotian.

His

concept of Eurasiatic was derived independently but overlaps with the proposed

Nostratic superfamily, the theory of which has been developed in the last 30

years by Russian linguists.

At

first sight it may seem hard to believe that languages as different as English

and Japanese, say, share any commonalities. But in his new book on the grammar

of Eurasiatic (a second volume on vocabulary is in progress), Dr Greenberg has

found many elements that he argues knit the major Eurasian language families

into a single group.

Words

beginning in ‘m’, for example, are found in every Eurasiatic family to

designate the first person (English: me; Finnish: minÃa;

proto-Altaic: min; Old Japanese: mi). Every branch of Eurasiatic,

Dr Greenberg says, uses n-words to designate a negative, from the no/not

of English to the -nai ending that makes Japanese verbs negative.

Every

branch uses ‘k’ sounds to indicate a question. In Indo-European, many Latin

interrogatives begin qu-, as in quid pro quo. In Finnish, -ko is

added to a verb to indicate a question. In Japanese the same role is played by

-ka. The word for ‘who?’ is kim in Turkish, kin in Aleut.

If

Dr Greenberg’s Eurasiatic proposal is at first no more favourably received than

his Amerindian classification, he will not be surprised.

‘A

fair part of my publications is just polemics,’ he says, with an air of

resignation.

Meanwhile,

Dr Ruhlen believes that if the Eurasiatic grouping is accepted, the world’s

5,000 languages can be seen to fall into just 12 superfamilies.

How

these in turn might be related to a single mother tongue remains to be seen.

But several years ago, Dr Greenberg identified a possible global etymology

derived from the universal human habit of holding up a single finger to denote

one.

In

the Nilo-Saharan languages the word tok, tek or dik means

one.

The

stem tik means finger in Amerind, one in Sino-Tibetan, ‘index finger’ in

Eskimo and ‘middle finger’ in Aleut.

And

an Indo-European stem deik, meaning to point, is the origin of daktulos,

digitus, and doigt – Greek, Latin and French for finger – as well as

the English word digital.

No

one has pointed more clearly at the one language than Joseph Greenberg.