Week 1

notes

What

is stylistics?

Stylistics

can generally be considered to be the study of literary texts with a sharp

concern for how the language element works in these texts. It is therefore one

of many different approaches to literary texts, in our case dramatic texts.

There are, for example, approaches that focus on sociological, psychological or

historical aspects of dramatic texts. Stylistics is different from ‘practical

criticism’ in that there is a belief that some rigour (in terms of description,

terminology, explicitness, etc.) is necessary — partly in the interest of

scholarship, but also because this will help the reader in reproducing

some of the procedures to other texts. The approach, therefore, contrasts with

the Leavisite approach.

Charles Bally published a two-volume

treatise on French stylistics (entitled Traité

de Stylistique Française)

in 1909. His concern was to describe the ‘affective’ aspects of language:

‘subjective but private feelings, attitudes, motives, perspectives, etc.’. Interest spread across continental

The rise of stylistics is also

related to the practical criticism method in literary criticism. Wimsatt and Beardsley’s essays, ‘The Intentional Fallacy’

and ‘The Affective Fallacy’ (1946) questioned the widespread reference to

influences and biographical details when criticising literary works. They felt

that dwelling on influences and biographical details allowed the critic to

almost totally ignore the text itself, and so the push was for there to be more

‘close readings’ (or explication de texte or

‘practical criticism’). The critical movement advocated (as stylistics did) a formalist

approach. A strong distinction was made between what was textual and

what was extra-textual. Extra-textual matters include biographical

details, the author’s intention, or socio-historical and cultural influences.

What was textual was what was found on the page itself. In fact, this kind of

stylistics, known as pedagogical stylistics, is often useful in teaching

literature to foreign- and second-language learners, in that it allows pupils

to tease out meaning from the text itself without making the pupil feel

threatened by lack of ‘background’ information.

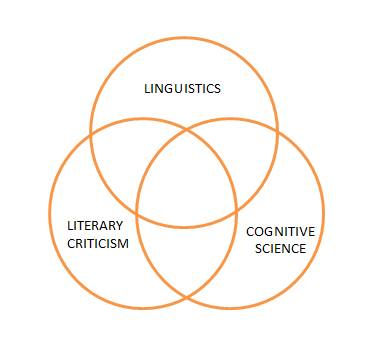

However, stylistics is, by

definition inter-disciplinary. In that it purports to deal with literary

texts, it has links with literary criticism and critical theory. In that it

believes that there needs to be some theoretical framework and fairly rigorous

methodology, it has links with linguistics and possibly sociology. This means

that stylistics has to take into account of developments in linguistics. As

linguistic descriptions take into account notions of context, and move beyond

the level of the sentence, more tools are made available for stylistic

analyses.

Stylistics draws upon theories

and models from other fields more frequently than it develops its own unique

theories. This is because it is at a point of confluence of many

sub-disciplines of linguistics, and other disciplines such as literary studies

and psychology, drawing upon these (sub-)disciplines

but not seeking to duplicate or replace them. This versatility of approach and

open-mindedness are, of course, characteristic of the humanities in general.

Instead, it takes a particular view of the process of communication which places the text at the centre of its

concerns, whilst being interested in the relationship between writer and text,

and the reader and text, as well as the wider contexts of production and

reception of texts. (Jeffries & McIntyre 2010: 3, my emphasis)

If you

are approaching stylistics with a background in literature, consider the

following questions:

If you

are approaching stylistics with a background in literature, consider the

following questions:

§ How do

you currently go about carrying out an analysis of a literary text?

§ Is the

kind of analysis you currently do satisfactory?

§ Is

there anything that you find difficult about the study of literature?

If, on the other hand, you are approaching stylistics from a background

in language study, think about the questions below:

§ What

constitutes data in the area of language study that you are most used to?

§ How do

you proceed when investigating a particular issue in the area of language study

with which you are most familiar?

§ Which

of the questions that arise in the study of the data you most frequently use do

you find difficult to answer?

|

Preliminary

task Imagine

you’ve been given the following passage (you probably know it), and you’re

asked to answer the question: what does it mean? Alternatively,

imagine you’re the English teacher to a class of 15-year-olds. What would you

tell your pupils? In

both scenarios, what additional information would you like to know?

|

Linguistics

·

Phonology is the study of how pronunciation

operates in particular languages.

·

Graphology is the study of the writing system,

also known as orthography — it includes spelling, punctuation, capitalisation,

handwriting style, etc.

·

Grammar is the study of the form of the

language (as opposed to the sound, writing, or meaning system of the language).

Grammar itself can be subdivided in syntax (sentence structure) and morphology

(word structure).

·

Morphology is the study about the structure or

organisation of words into morphemes — the ‘roots’ (‘stems’) and affixes. A

morpheme is the smallest distinctive unit of grammatical analysis. The word gleeful

contains two morphemes: glee (the ‘root’), and ful

(the affix); the word advantage contains one morpheme only.

·

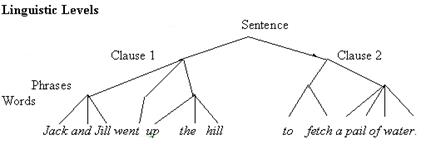

Syntax is the study of the structure or

organisation of sentences into clauses, phrases and words. There is concern,

for example, on how the information is focused in a sentence, or on how the

words are ordered.

·

Discourse Analysis is a term that is not very

clearly defined — some use it to refer to the organisation above the sentence

level (e.g., how sentences are organised into paragraphs); some focus on spoken

discourse (as opposed to written text). In TS4213, we shall use the term discourse

to refer to bits or stretches of language including the context to which the

language is used (who said/wrote what to whom, when, why?). We can therefore

restrict the term text for the ‘written record’ of spoken or written discourse.

·

Semantics is that aspect of linguistics that

formally studies the meaning aspects of language — specifically of words and

sentences, without necessarily taking into account the context in which they

are used.

·

Pragmatics is the study of utterances as opposed

to sentences. Each single instantiation of a sentence constitutes a different

utterance. For example, I can say, ‘It’s late’ when my friend suggests that we

go out for a drink. The next day, I can say ‘It’s late’ to my wife after being

at a dinner party for several hours. I have said the same sentence, but I have

made two utterances. The first utterance might mean ‘No, I can’t go out with

you now’; whereas the second might mean ‘My dear, I think it’s time we

considered going home’. Pragmatics is therefore concerned with utterance

meaning, and attempts to relate the form and sentence meaning systematically to

the context.

This

can be summarised as follows. Given that we are interested in dramatic

discourse, our reliance on linguistics will be mainly from pragmatics

and discourse analysis.

Linguistics

|

|

SUBSTANCE |

FORM |

MEANING

|

SITUATION

|

|

Spoken

Language

|

phonology |

grammar (morphology

and syntax) |

semantics |

pragmatics

(discourse analysis)

|

|

Written

Language

|

graphology,

orthography

|

(All

the words have one morpheme each except for went: go + [past tense].)

Semiology/Semiotics

I

make no distinction between semiology and semiotics. The former

is favoured especially in

Human language is one example of a

sign system; but it is not the only method of communication. Apart from

language, people can also communicate by facial expressions and gestures (body

language), or through their accents (normally considered paralanguage because

although it is not a linguistic element, it accompanies language), or through

the kinds of clothes they wear (obvious examples would be the wearing of school

ties, football club colours, or wearing ‘mourning colours’, or a man not

wearing a tie at a formal function), or the style or colour of ones hair. The study of visual communication is normally

known as kinesics.

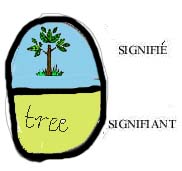

The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de

Saussure (1857–1913) introduced a terminological distinction which has

exercised a major influence on subsequent linguistic discussion: signifiant (or ‘signifier’, or ‘significans’)

was contrasted with signifié (or ‘concept

signified’, ‘significatum’).

For

the most part (in language), the relationship between the signifiant

and the signifié is arbitrary. Exceptions

would be onomatopoeic words (like ring or mew).

Other kinds of symbols might be less

arbitrary. In the work of Charles Peirce (1931–58), there are three major types

of signs: an icon is a signifiant which

resembles in its form the signifié; an index

is a signifiant which is related to the

signifié in terms of

contiguity or proximity or causality; a symbol is a signifiant

which is arbitrarily related to its signifié.

Examples of icons would include

photographs, certain map and road signs (e.g. the cross-roads symbol, or

T-junction symbol). Examples of indices include thunder and lightning

(indicating storm), smoke (indicating fire), spots (indicating measles, chicken

pox, etc.), a person staggering (indicating drunkenness or exhaustion), a

person stuttering (indicating nervousness). Stage performances therefore rely

partly on indexical signs for communicating to the audience information about

the characters, etc.

The

notion of indexicality

has also been used more generally than the way employed by Peirce. It refers to

how there can be non-propositional

components of linguistic meaning. This notion is useful for stylistics.

Compare

the 1930s British traffic sign for a school and a contemporary one. How are

they different?

The

stylistics of drama is therefore a semiotic approach to dramatic texts,

which focuses on the linguistic elements of the text (but should also be

cognisant of other elements in the text). It is one of several

possible approaches. It is closely related to ‘practical criticism’, but

prefers an explicit analysis, with clear and unambiguous terminology, supported

by some theoretical framework.

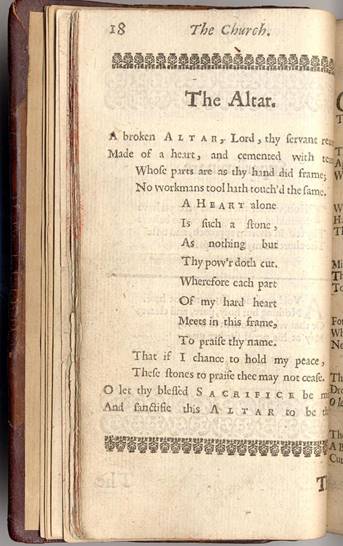

Also,

consider the following poem by George Herbert (1583–1633):

The Altar

A broken ALTAR, Lord, thy servant rears,

Made of a heart and cemented with tears;

Whose parts are as thy hand did frame;

No workman’s tool hath touch’d the same.

A HEART alone

Is such a

stone,

As nothing but

Thy pow’r doth cut.

Wherefore each part

Of my hard

heart

Meets in this frame

To praise thy name.

That if I chance to hold my peace,

These stones to praise thee may not cease.

Oh, let thy blessed SACRIFICE be mine,

And sanctify this ALTAR to be thine.

DISCUSSION

1

How many levels of semiosis can

you discern in George Herbert’s (1593–1633) poem below?

Easter Wings

by George Herbert

![]()

Lord, Who createdst man in wealth and store, 1

Though foolishly he lost the same, 2

Decaying more and more, 3

Till he became 4

Most poore: 5

With Thee 6

O

let me rise, 7

As larks, harmoniously, 8

And sing this day Thy victories: 9

Then shall the fall further the flight in me. 10

My tender age in sorrow did beginne; 11

And still with sicknesses and shame 12

Thou didst so punish sinne, 13

That I became 14

Most thinne. 15

With Thee 16

Let me combine, 17

And feel this day Thy victorie; 18

For, if I imp my wing on Thine, 19

Affliction shall advance the flight in me. 20

![]()

We can examine Widdowson’s

analysis of Frost’s poem.[1][1]

DISCUSSION 2

Let us discuss the poem first.

Here is the poem in full.

Stopping by

Woods on a Snowy Evening[2][2]

Whose woods these are

I think I know. 1

His house is in the

village, though; 2

He will not see me

stopping here 3

To watch his woods

fill up with snow. 4

My little horse must

think it queer 5

To stop without a

farmhouse near 6

Between the woods and

frozen lake 7

The darkest evening

of the year. 8

He gives his harness

bells a shake 9

To ask if there is

some mistake. 10

The only other

sound’s the sweep 11

Of easy wind and

downy flake. 12

The woods are lovely,

dark, and deep, 13

But I have promises

to keep, 14

And miles to go

before I sleep, 15

And miles to go before I

sleep. 16

We

can possibly focus on many kinds of linguistic patterning in this poem — for

example, the rhyme scheme; the alliteration in dark, and deep; the

contrast between the words relating to the man-made elements (house,

village, farmhouse) and the natural elements (woods, snow). Widdowson, among other things, focuses on the pronoun

system (Whose woods, his

house, my little horse, etc.). He suggests that some of the usage is

unusual, and therefore catches his attention, and that this requires

interpretation. He suggests that the poem has as its theme ‘the reality of

social constraints, of rights and obligations, in opposition to that of natural

freedom [symbolised by the wood, wind and snow]’ (p. 121).

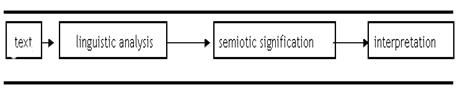

We can trace the steps, rough, as

follows.

And

this is fairly typical of most stylistic analyses. We examine the text, look

out for linguistic patterns, and then try to work out the relevance or

significance of the discovered pattern. This then should lead to some sort of

interpretation of the text. The assumption is that the author is trying to communicate

something through the patterns we have discovered. In other words, the

patterns function as a sign — we have to decide how to interpret

the sign (is it iconic, or indexical, or symbolic in Peirce’s sense?). We talked about indexicality earlier: this is

another way to think about significance.

When Widdowson’s

article appeared, Sydney Bolt objected to what he felt to the ‘obvious’ Death

Wish interpretation of the poem:

When

the reader thinks twice about what the last line means [‘And

miles to go before I sleep’], he realises there must be a latent meaning

beneath the manifest one. This reveals itself as a metaphor — ‘a long way to go

before I die’. On re-reading, one now registers the attractive woods as the

Widdowson’s own comment was that this was

‘altogether too weighty a construction to place on this single repetition, and

[he] saw no warrant in the actual text for [this] interpretation’. How then do

we explain the prevalence of this interpretation? It would seem that literary

texts, in particular poetic texts encourage

symbolic readings (and I am using ‘symbolic’ in the general sense now). We can

make the jump from sleep to death through the similarity between

them (an index), and perhaps also through conventional usage (‘he’s gone

to sleep’ = ‘he has died’). But all this is probably reinforced by the

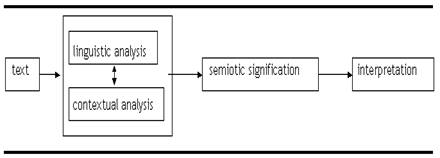

conventions of poetry. My point is that the language element and the contextual

element both figure in the way we come to a conclusion about the text we are

reading, and we can therefore expand our model.

The context of the words

(being found in a poem) therefore allows for this kind of reading, and the word

sleep takes on additional semiotic significance. Our model of stylistics

then should therefore encompass contextual analysis together with linguistic

analysis.

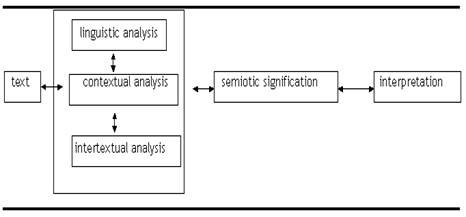

I propose also another extension to

the model. If we bear in mind the Frost poem again, we might also want to say

that the theme or notion of sleep harks back to previous usages

and previous significations of the word sleep. In other words,

words (or even structures) can have histories. The way we use particular words

(or structures) depend on our past, historical experience of the words (or

structures). In general, we can say that if a particular word (or structure)

has a history of being given a particular semiotic signification,

it will subsequently be easier to give that particular semiotic signification.

We might therefore say, for example,

that the Frost poem makes us think of, say, Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale’:

Darkling

I listen [to the nightingale]; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with

easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet

breath;

Now

more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the

midnight with no pain,

While thou art

pouring forth thy soul abroad

In

such ecstasy!

Still

wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain —

To thy high requiem

become a sod.

…

Adieu!

adieu! thy plaintive anthem

fades

Past the near meadows, over the

still stream,

Up the

hill-side; and now ’tis buried deep

In

the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that

music: — Do I wake or sleep?

Keats

makes uses many lexical items to do with, or closely related to, the notion of

death — Death, die, cease, soul, requiem, sod, buried. He also uses

lexical items to do with sleep — dream, sleep. The reader is thus

encouraged to make the connexion between sleep and death. A reader may

therefore allow this other text (Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale’) colour his/her

interpretation of Frost’s poem. Or, to put it another way, Frost might have

been (consciously or sub-consciously) recalling Keats’s ode whilst writing his

poem. We can say that the text harks back to another text, or that there

is intertextuality — some sort of a connexion between these two texts.

Writers and readers are generally not like, say, computers and have experience

of other texts, and they frequently make use of their experience of other texts

to interpret new texts. Whether the reader recalls Keats’s ode or perhaps even

just the Bible:

As

they were stoning him, Stephen said in invocation, ‘Lord Jesus, receive my

spirit.’ Then he knelt down and said aloud, ‘Lord, do not hold this sin against

them.’ And with these words he fell asleep. [Acts 7.59–60, The New Jerusalem Bible]

this is a resource that is available for

interpreting texts. We can therefore again extend our model of stylistics to

incorporate this.

It

could well be argued that intertextuality is just another element of the

context; I prefer to keep another box for intertextual analysis merely to

emphasise that this is another important resource for semiotic signification. I

therefore make a three-fold distinction between:

the linguistic

elements

— the actual words and structures;

the

contextual elements

— the surrounding text (or ‘co-text’), who is writing/speaking to whom, when,

where, on what occasion/for what purpose (or the ‘addresser’, ‘addressee’,

‘time’, ‘place’, ‘function/purpose’); and

intertextual elements — the

‘histories’ of words or structures, or how a text can ‘recall’ another text.

I have used double-headed vertical

arrows to indicate that each element can inform on the other elements. I have

also used double-headed horizontal arrows to indicate that the path to

interpretation is not necessarily uni-directional.

One may, for example, be already predisposed to particular lines of

interpretation, and therefore seek out particular elements for semiotic

signification; and in the process of analysing the text one may also modify

one’s original interpretation.

DISCUSSION 3

Examine the following extract

from a contemporary British play.

henry:

Hallo, Henry Bell.

karen:

Henry’s from our accountants. And this is Anthony and Imogen Staxton-Billing.

(She

immediately moves away to the other group.)

henry:

Ah, hallo.

anthony:

(Cursorily) ’Llo.

(They

shake hands.)

henry:

(Turning to imogen)

Hallo, Henry Bell.

(imogen scarcely

looks at him but gives him the most peremptory of greetings and handshakes.)

imogen:

(Glacially) Hallo.

daphne:

Did she say you were an accountant?

henry:

(Defensively) Yes.

daphne:

Oh. (She looks him up and down.) Not local, are you?

henry:

No.

daphne:

Yes, I thought as much. Excuse me, I just want a word

with …

(She

drifts away to the other group.)

henry:

(Charmingly) Of course. (Turning to the staxton-billings) Well. A lot of people to meet all of a sudden.

imogen:

(Ignoring him, to her husband) Did you know she

was going to be here?

anthony:

Who?

imogen:

I’m talking about that little toad, Karen Knightly. Who do you think I’m

talking about?

anthony:

Oh, Karen. That’s who you’re talking about.

(Slight

pause.)

henry:

Did you have far to come?

imogen:

(Ignoring him still) God, you bastard. You let me come to this house and

walk straight in to her. And you never even warned me she’d be here.

anthony:

Oh, do put a cork in it …

imogen:

I mean it’s so cruel, Anthony. Don’t you realise how cruel it is? Don’t you

honestly realise?

anthony:

Oh, God. It’s one of those afternoons, is it?

(He

starts to move away.)

imogen:

Anthony …

anthony:

Goodbye.

(He

goes to talk to daphne

who has joined up with percy. Pause.)

henry:

(Trying again) What’s this committee in aid of

then? Is it for some charity?

imogen:

What? Are you talking to me?

henry:

Er … yes. I was … I was just …

imogen:

Listen, I don’t think we have a thing in common, do we? I’m sure you have

nothing to say that would be of the slightest interest to me. And there’s

nothing whatever that I want to talk to you about. So why don’t you just run

away and practise your small talk with somebody else?

(henry is

totally staggered by her rudeness. Before he can even begin to think of a

retort, imogen moves away from him.)

What do we make of this extract?

I shall fill you in on the contextual elements later. Try to relate our

impressions or interpretations of the extract to the linguistic elements. If

there are divergent impressions or interpretations, so much the better.

·

Note

down the style (‘feel’) of this particular passage.

·

Relate

the ‘style’ or ‘feel’ to elements in the language.

·

Discuss

the significance of this.

·

Now

try to distinguish between the characters’ speech styles. It might be possible to

note developments in the speech styles of individual characters.

Carter

and Stockwell (2008) include this Stylistics

Manifesto at the end of their book. At the end of the module, we might want

to evaluate the degree to which we have lived up to this!

1. Be theoretically aware. As

stylisticians we should be alive to the theoretical

foundations of the different interdisciplinary foundations domains on which we

draw, as well as of linguistic theory.

2. Be reception-oriented. The

literary ‘work’ only exists as a text in the mind of a reader; this fact should

be at the forefront of stylistic practice. Interpretation is not an ‘add-on’

feature but is a foundational principle with texture at its analytical centre.

3. Be sociolinguistic. We

should not neglect the broad sense of language study, taking account of the

social, cultural and ideological dimensions of reading.

4. Be eclectic. Stylisticians

should be eclectic as a matter of principle, in terms of analytical tools and

analytical projects.

5. Be holistic. We

should be aware that classification, categorisation and the focus on features

are analytical conveniences, and we should always re-contextualise the products

of our analyses.

6. Be populist. Stylisticians

should continue to challenge the literary canon, promote new configurations of

literariness, appreciate and demonstrate their value.

7. Be difficult. Being

populist does not exclude the courage to demystify obscurity and wilful

inarticulacy in theory, nor avoid challenging works of literary. The difficult

edges of literature are where we should stretch and test our frameworks rather

than simply illustrate and demonstrate their effectiveness.

8. Be precise. Stylistics should continue to uphold the

highest standards of analytical precision and transparency of practice. We must

be rational, rigorous, systematic, thorough and open.

9. Be progressive. We should aim for a better account of things.

Where an approach is shown to be faulty, it should be repaired or discarded. In

other words, we should aim for a stylistics of falsifiability.

10. Be evangelical. Stylistics

is the best approach to literary study. We should be unapologetic about this,

and should deploy all our rhetorical resources to continue to draw in

enthusiastic and committed researchers, teachers and students, and continue the

development of the field.

© 2020 Peter Tan