|

Let us begin by defining the two relevant terms.

What do we understand by “humanism”? The term evokes three or four broad

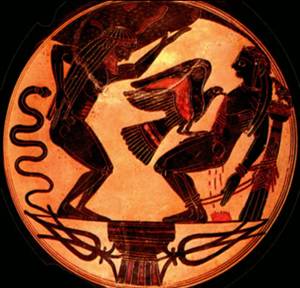

connotations. The first derives from Greek philosophy, specifically from

the call by Socrates (in the fourth century BC) to turn philosophical

speculation away from its then current preoccupations with the nature of

the universe and the “heavens” towards more mundanely terrestrial human

interests and preoccupations.

Jacques-Louis David, The Death of

Socrates (The Met, New York)

The second sense is associated with the European Renaissance and its

enormous interest in human accomplishments as contrasted with religious

concerns, as reflected both in the interest taken by Renaissance

intellectuals, scholars and artists in the accomplishments of classical

Greece and Rome, and in contemporaneous preoccupations with human

agency, human institutions and the human potential for self-fulfillment.

The third sense arose in the 19th century, when Darwinian speculations

and evidence for the origins of the species went against the grain of

fundamentalist Christian doctrine, resulting in the notion of a rational

humanism that challenged the literal veracity of the narrative enshrined

in the first book of the Bible (and all such accounts of origins derived

from religious sources). The fourth sense, which we are going to focus

on today, assimilates features from all the previous three connotations,

and can be illustrated through the use of the contemporary term

“Humanities” to describe that part of the educational curriculum which

devotes itself to the study of specifically human concerns, institutions

and creativity as contrasted with the type of study we commonly

associate with the natural sciences (specifically astronomy, physics,

chemistry and also mathematics) and with life science and the social

sciences. Thus the term “humanistic” acquires significance through

contrasts developed through the course of history between the kinds of

subjects or areas about which human beings have aspired to create

cumulative and systematic knowledge and understanding, distinguishing

human preoccupations and interests from interest in, knowledge of, and

the manipulation of the physical universe. Humanists base their approach

to value, knowledge and meaning on human reason, human concerns and

human aspirations for truth, goodness, beauty.

Next, let us focus on the term “technology”. One way of describing the

scope of the word is to recognize that its current significance is

linked to the capacity of the hard sciences to create systematic

knowledge about the physical world we live in; this knowledge, when put

to practical use and applied to material nature, through various

techniques and processes, leads to the transformation of material

reality through the creation of new structures, materials and entities.

In short, a technology might be described as the technique of

transforming material reality through the application of scientific

knowledge and method to the objects and entities of the world.

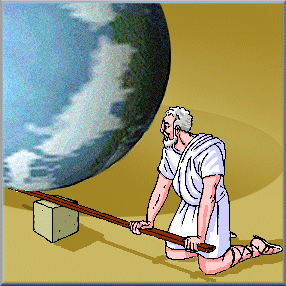

Link 1:

Archimedes: “Give me a place to stand on and I will lift the earth”

As soon as we have defined the two terms we begin to recognize how they

have arrived at a kind of diagonal or oppositional relation to one

another which is – unfortunately - a legacy from the history of human

institutions that leads to the kinds of simplifying polarizations that

set the Sciences in some allegedly oppositional relationship towards the

Arts. Many have argued for this opposition as a mistake, but even as a

mere prejudice, the alleged opposition is already well-entrenched in

society and in the minds of many people, and one of the aims of this

lecture is to help clarify what is at stake in untangling the alleged

opposition between Science and Art or Technology and the Humanities. I

shall follow a two-step process towards this untangling. In the first, I

shall work with the opposition as a given assumption or prejudice among

societies, and examine the consequences of that prejudice, specifically

from a perspective originating in the arts and humanities. The second

step will deliberately go in a slightly contrary and more constructive

direction, and argue that the relation of technology to a more balanced

or sensible humanistic perspective can show the alleged opposition as

harmful to human progress, and in need of resolution, both in individual

mind-sets and in broad social assumptions of value about the respective

roles of science and art in society.

Link 2:

Frederick Edwords, What is Humanism?

Link 3:

Richard Norman on Humanism (audio)

|