EL2111

HISTORICAL VARIATION IN ENGLISH

English

spread: settlement – English in North America

Introduction

In our story of

English so far, we have established that with the re-establishment of English in

Britain at the end of the Norman period, the stage was set for the language to

develop. The process of standardisation referred to earlier meant that the East

Midland dialect was established as the dialect to be developed. This period

also coincided with the spread of the English language as momentum gathered for

the discovery of new territories and the desire to get access to raw materials

that would feed the industries that were coming up.

Many scholars make

a distinction between colonies for

settlement and colonies for economic

exploitation. The former involved large-scale movements of population

whereas the latter did not. The difference is significant from the point of

view of the spread of the English language. In this segment, we will consider

the spread of English to North America as representing the spread through

settlement colonies.

Bifurcation

With the population

movement to the so-called New World starting just before the time of

Shakespeare – just at the time when standardisation in Britain was gathering

momentum – we might expect this to lead to a bifurcation of standards. Choices

made in one realm might be divergent from choices made in another realm

separated by 3,000 miles of ocean.

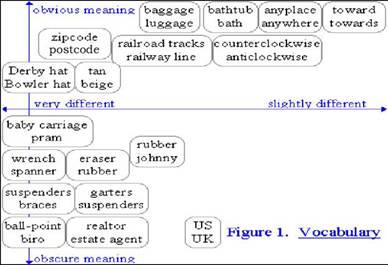

To a certain

extent, that did take place. The terminology that developed in relation to the

motor industry illustrates this very well. West of the Atlantic, speakers refer

to the hood, trunk and windshield; east of the Atlantic,

speakers refer to the boot, bonnet

and windscreen.

Early expeditions

The early expeditions

ended up in failure mainly because the people were largely unprepared for the

new conditions. In 1607, however, the first British colony was established in

Jamestown in Virginia. Much is often made of the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ – Puritans who

disagreed with the practices of the established church – who were trying to

escape the sectarian persecution in Europe in the throes of the difficulties

arising out of the Reformation, and voyaging across in the Mayflower. Here is

Felicia Heman’s poem about that episode where the

Pilgrim Fathers are cast as heroes.

The breaking waves dashed high

On a stern and rock-bound coast,

And the woods against a stormy sky

Their giant branches tossed;

And the heavy night hung dark,

The hills and waters o’er,

When a band of exiles moored their bark

On the wild New England shore.

Not as the conqueror comes,

They, the true-hearted came;

Not with the roll of the stirring drums,

And the trumpet that sings of fame;

Not as the flying come,

In silence and in fear;

They shook the depths of the desert gloom

With their hymns of lofty cheer.

Amidst the storm they sang,

And the stars heard, and the sea;

And the sounding aisles of the dim woods rang

To the anthem of the free.

The ocean eagle soared

From his nest by the white wave’s foam;

And the rocking pines of the forest roared –

This was their welcome home.

There were men with hoary hair

Amidst the pilgrim band:

Why had they come to wither there,

Away from their childhood’s land?

There was woman’s fearless eye,

Lit by her deep love’s truth;

There was manhood’s brow, serenely high,

And the fiery heart of youth.

What sought they thus

afar?

Bright jewels of the mine?

The wealth of seas, the spoils of war?

They sought a faith’s pure shrine!

Ay, call it holy ground,

The soil where first they trod;

They have left unstained what there they found –

Freedom to worship God.

The

thirteen colonies

The

thirteen colonies

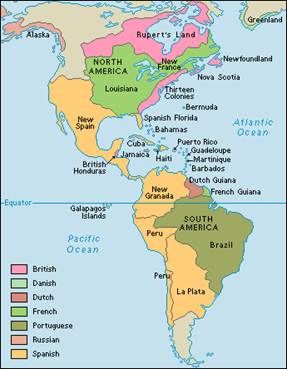

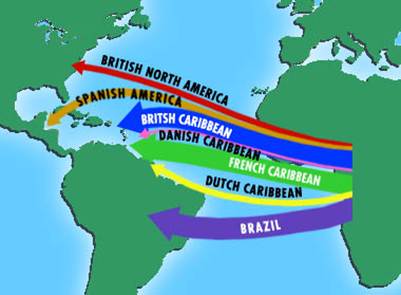

By 1733, there were

13 British colonies established along the eastern seaboard of North America.

The population were mainly British and came from various regions in Britain,

and the English spoken there must still have a clear British character. Britain

was not the only colonial power in search for new lands. In the 18th century,

the French, the Dutch and the Spanish were well represented in North America.

The British had

already taken control of Dutch territories in the 17th century – New York was

originally New Amsterdam; New Sweden is now Delaware.

All was not well,

however, and when the British king (George III) imposed strong control over the

colonies, they rebelled. The American Revolution is the term used to refer to

these upheavals between 1765 and 1783. Particularly stinging were the taxes

imposed by the crown, and that the colonies were not represented in Parliament.

‘No taxation without representation’ was the cry heard at the time.

The Patriots (colonists who protested about

the current state of affairs) also had strong republican sentiments.

In 1773 the

Patriots cast overboard heavily taxed tea in protest. This came to be known as

the Boston Tea Party. The British

responded by enacting tough laws against the colonists, the Coercive Acts,

which resulted in heavy fighting. Not everyone supported the Patriots. There

were Loyalists who still supported

the British crown.

The Patriots formed

the Provincial Congress to take control of the governing of the 13 colonies,

and to fight Britain (the ‘redcoats’ – the British infantry regiment wore red

coats at the time) and the Loyalists. The leader of the Continental Army,

General George Washington made the Declaration

of Independence in 1776. The declaration itself was composed mainly by

Thomas Jefferson, and the second sentence is the most well

known:

We hold these

truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are

endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,

that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

The British were

forced out eventually and the Treaty of Paris in 1783 ended the conflict

formally. Loyalists fled up to Canada which remained British.

Other groups

Apart from the

Dutch and French who were already in the scene, there were other groups in

North America who would continue to influence the English language spoken

there. These include:

•

Native

Americans (‘Red Indians’)

•

Irish:

esp. after the potato famine 1846–50

•

Scots

•

Germans,

Italians, Scandinavians

•

Jews

•

Hispanics

Not to be forgotten

is the significance of the slave trade in altering the population make-up of

North America.

The American Civil War

(1861-65) that ensued was largely to do with the difference in attitudes to the

slaves between the North and the South (the Confederate States who declared

themselves independent from the Union). When the South lost, slavery was

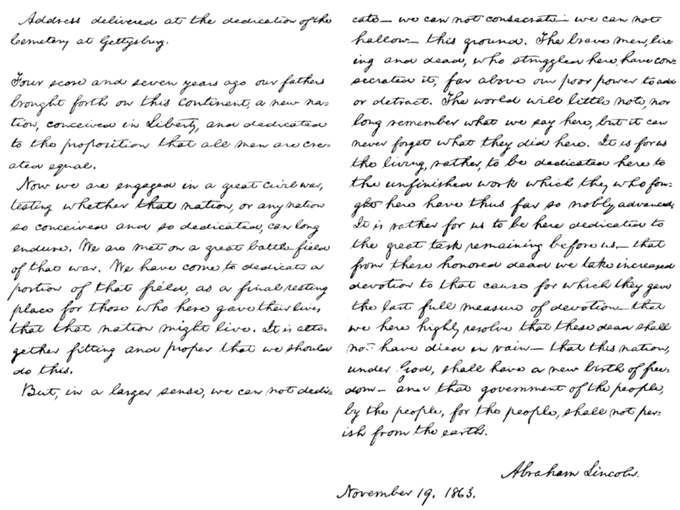

abolished, and Abraham Lincoln gave his well-known Gettysburg address:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this

continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition

that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can

long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to

dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here

gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and

proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate,

we can not consecrate, we can not

hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have

consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will

little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what

they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the

unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It

is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before

us—that from these honored dead we take increased

devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of

devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in

vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that

government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from

the earth.

Here is a facsimile

of the document:

We might wonder

about the extent to which this represents American English as opposed to

British English. We might notice the spelling honored rather than honoured. In the 19th century, however,

this spelling was not considered specifically American. Both –or and –our forms alternated, and the English writer Charles Dickens is

known to have preferred the –or

forms. (If you have looked at the Shakespeare quarto texts, you will also have

noticed both forms.) The date format November

19, 1863 is commonly considered American, but at that time this would have

been normal in Britain as well. Many British newspapers continue to retain this

date format in their house styles.

The formulation ‘four

score and seven years’ is dated at this time and possibly picks up the style of

the King James (Authorised Version) Bible of 1611. Compare this to the words

from Psalm 90: ‘The days of our years are threescore years and ten; and if by

reason of strength they be fourscore years, yet is their strength labour and

sorrow; for it is soon cut off, and we fly away’ (verse 10). This pointedly

reminds us that Americans were still dependent on published material from

Britain.

We will watch a

video which will summarise the main developments in American English from the

time of the American Revolution to the Second World War. There is a scoring

chart to help summarise its content.

Expectations

Two

natural expectations about the variety that emerged. Given the various influences on and inputs

into English in America, two expectations are raised about this variety:

I . That it would be hugely

diversified

a. Because it was drawn from a variety of

different British sources prior to

standardisation

b. It had to adapt to a radically new

environment, and accommodate a massive diversity of peoples, cultures,

languages, backgrounds, etc.

c. It had to innovate, because the country and

the people had no prior, established or institutionalised frameworks of

decision making, action, etc. that they could simply apply to life and

experience in their new context.

II. That English in America would be a unique entity,

considerably differentiated from the ‘mother language’, British English

· In fact, there was early talk about ‘American’ rather than ‘English’ as the name of the language (Thornton1793)

· By 1850, Americans did have a version of English that was recognisably their own.

· It was also felt that this variety would develop somewhat separately from the ‘mother language’.

· H L Mencken: the differences will ‘go on increasing’.

The failure of both expectations

However, both these

expectations were not met.

I. Uniformity

However, instead,

when compared with the hugely differentiated British English, there appears to

me much more uniformity: ‘… the image of a uniform American English

sharply contrasting as a whole with any part of the extremely heterogeneous

English of Britain is one that has seemed soundly based for more than two

centuries by observers in both communities’ (Randolph Quirk, The English Language and Images of Matter).

There are three

broad varieties corresponding with three broad areas:

The East is

‘clipped’, the West is ‘broader’ and the South was influenced by Black speech.

II. Lack of distinctiveness

The Puritan

settlers from England, many of whom were middle class people who aspired to rid

themselves of the controls of the old order of society, with its aristocracy

based on birth, inherited privilege, etc. They also wanted to have free rein to

pursue their economic goals, self-advancement, etc. This immediately meant

that their outlook was anti-élitist and

individualistic, and they could be expected not to want to conform to the ways

of the old country.

However, comments

from observers indicate a lack of distinctiveness.

·

In

fact, ‘extraordinary unanimity . . . exists over the bulk of the language’

(Quirk, p. 30)

·

American

English shows great similarities with British English in ‘grammatical structure

and syntax – essentially the operational machinery of the language’ (A H Marckwardt, American English)

·

‘there has been little divergence of British and American

English. Many of the indubitable linguistic differences between a given

American and a given Briton are individual differences, social differences, or

differences that reflect dialectal variation within one or other community:

they often do not, in other words, reflect differences between British and

American English as such’ (Quirk, p. 26)

As mentioned above, there are clearly some lexical differences between AmE and BrE: trunk/boot,

petrol/gas(oline),

biscuits/cookies, chips/French fries, crisps/chips, bill/check, lift/elevator,

caretaker/janitor, aubergine/eggplant, dustbin/garbage can, bookshop/bookstore,

chemists or pharmacy/drugstore,

the ground floor/the first floor, hire out/rent

out, the first floor/the second floor, post/mail (a letter)

However, we might

also note these:

postcard, postage stamps, post office, postal

service in America

mailbags, mail trains, Royal Mail, airmail in Britain

Reasons

There is sometimes a lot of reference to ‘natural’ tendencies in particular

situations. These include:

·

‘accent

levelling’, etc. because of the diversity

·

The

early settlers’ speech was comparatively uniform, since it had a ‘larger than

average proportion of educated use’ and reflected the tendency ‘for educated

people to have a concept of standard English transcending regional

dialects’ (Quirk, P. 4)

·

There

was a strong urban bias from the beginning, with an emphasis on schooling and

the existence of an institutionalised education system.

·

The

population was very mobile, and the mobility was facilitated by the rapid

growth of communications (railways, etc.). This worked against local accents

and peculiarities.

Such ‘natural’

explanations are extended also to account for the pre-eminent position English

won for itself in the new land, selecting itself inevitably as the language of

the place. In the 1790 census, 90% of the population indicated they were were English speaking. The extension of the sway of English

would appear to be inevitable and natural.

There is an interesting

two-sidedness in the development of AmE, with the

reality not always matching the apparently espoused ideals. On the one hand,

there is a lot of rhetoric emphasising individual self-realisation, initiative,

opportunity, rights, open-endedness, pluralism, democracy, freedom, anti-élitism, and so on. There are therefore, for instance,

frequent remarks on innovativeness, etc. reflecting the unique individualistic

American experience, invention and so on (as contrasted with British

‘censoriousness’).

At the same time,

however, differences were ironed out under the pressure of a common enterprise

whose nature was essentially determined by the original dominant New England

settlers driven by economic goals and interests. From the beginning, there was

‘an experience of struggle and difference’ which needed to be ‘erased’ in

pursuit of an image of unity and solidarity for the survival of which ‘certain

interests had to be excluded or co-opted’ (David Simpson, The Politics

of American English). It is sometimes difficult to see this, because ‘by

about 1850, democracy had become the dominant American ideology or self-image,

so that, in the continuing development of a self-declared pluralistic culture,

a struggle of languages has been the harder to perceive where it does

exist.’ But, it did take place, and its result was the loss of ‘the

discourse once available to describe the differences and tensions’ of (the)

polity. (Simpson)

During the 150

years between settlement and Independence, the dominant groups at the helm of

the creation of this new society were afflicted by insecurities. These included

the uncertain and potentially environment; and the perception of difference and

diversity being a major problem. These could constitute obstacles to the

pursuit and achievement of their economic and political goals. Therefore, they

looked for a common language on ‘national’ principles to establish solidarity

and unity and to preserve the socio-economic system, within which they had the

dominant role.

This represented a move towards homogeneity and uniformity based on the

interests of the powerful. The official rhetoric talks about a melting pot concept, whereby

‘individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men’,

and this is achieved through assimilation, homogenisation, and also elimination

of rivals.

The end result was

the establishment of the hegemony of the powerful groups: a new kind of

‘aristocracy, based now not on birth (as in the case of the old aristocracy

they had resisted), but on wealth, power, and individual initiative and

enterprise.

Events in the process

1.

Elimination of pre-existing populations

Initially,

and for centuries after, there was the ruthless expropriation and elimination

of the native Indian population along with their languages. French, Spanish, etc. who were already in

some of the territories which America incorporated, were marginalised or pushed

out. There is also, currently, an English

Only movement in various states in the US.

2. Political and linguistic independence from Britain

After the challenge

to the political and economic hegemony of Britain, the dominant groups in

America affirm their political dominance within the country. A linguistic

reflex of this was the assertion of linguistic independence.

From very early

times, there had been negative evaluations of American usage in Britain: bluff, lengthy,

belittle, placate, antagonise, presidential – ‘the American dialect, a tract (= process)

of corruption to which every language widely diffused must always be exposed’

(Dr Johnson: 1756).

Around the time of

the War, claims began to be made on behalf of the English used in America: ‘As

an independent nation our honour requires us to have a system of our own, in

language as well as government. Great Britain, whose children we

are, should no longer be our standard. . . . . A national language is

a band of national union. Every engine should be employed to render the

people of this country national; to call their attachment home to their

own country; and to inspire them with the pride of national character’ (Noah

Webster, Dissertations on the English Language, with Notes

Historical and Critical).

In 1802, the US Congress referred to ‘the American Language’. In 1828,

Webster’s 2-volume An American Dictionary of the English Language was produced ‘to ascertain the

national practice’

3. Perception of linguistic diversity as an obstacle to political and

cultural unity

Once the external

political battle had been won, attention turned explicitly to the internal

problems. Difference and variety were seen as a problem, generating

instability, a threat to civil society within which the position of the

dominant group was otherwise assured. They saw a relationship between

linguistic discord and social discord ie,

language has the potential for fostering political and cultural unity, or, if

it goes wrong, could lead to disorder.

This thinking draws

very much on similar thinking in Britain which also legitimises its middle

class dominated status quo in this way. These considerations explain the great

deal of talk about a ‘common language’ in establishing a common internal unity

or the identity of the nation. This ‘common language’ was not to be allowed to

accommodate all the variation that actually existed, and the claims of various

interests, factions, etc. had to be excluded or co-opted, that is, it was meant

to be a brake on variation in the interests of the dominant groups. The focus

now falls instead on a standard language, as a means of bringing variety under

control. Thus, Webster, the nationalist, eventually abandoned some of his

earlier recommendations for spelling in his Dictionary: bred, tuf, tung,

thum, iland, wimmin. There

are just a handful of differences in spelling.

|

BRITISH |

AMERICAN |

|

colour |

color |

|

honour |

honor |

|

centre |

center |

|

theatre |

theater or theatre |

|

defence |

defense |

|

mould |

mold |

|

cheque (as

in cashing a cheque) |

check |

|

dialogue |

dialog or dialogue |

|

through |

through or (informal)

thru |

|

programme (except computer

programs) |

program |

|

omelette |

omelet |

4. The establishment of a standard based on the usage of the educated

class

This standard was

based on the usage of the ‘well-educated yeomanry’ of New England (yeoman

= a farmer who owns and works his land), who ‘speak the most pure English now

known in the world’; not the ‘illiterate peasantry’, but ‘substantial

independent freeholders, masters of their own persons and lords of their own

soil’ are the standard bearers.

The usage selected

is the usage, essentially of the property-owning, educated class of New England

and the Virginia groups of settlers, ie the most

powerful in society. These become the dominant white middle class group, and

the usage of this class is taken to define the favoured American English usage.

5. The British orientation of the

standard selected

The standardising

impulse was expressed around the ‘central (British) tradition’ which was

retained far more ‘than is commonly supposed to’ (G P Krapp, The

English Language in America). The usage of these dominant groups was

predominantly influenced by south-eastern British speech, which formed the

basis of Standard British English: ‘Many of the principal immigrants to this

country were educated at the English universities’ (Webster 1836). The

establishment of the education system in America almost at the very start

reinforced this orientation.

The widely-held

idea that the development of the standard language in America should be in the

hands of great writers, an authoritative ‘senatorial class of men of letters’,

who by developing the language in the desired manner would guard it against the

ravages of populism and the interventions of those who needed to be kept out (Simpson,

p. 47). But such a group of writers was not believed to have yet come into

being. Therefore, there was no alternative but to go to the established British

standard, the further advantage of which was that it was itself the dialect of

the dominant middle class in England.

Therefore, Webster

conceded that ‘The body of the language is the same as in England and it is

desirable to perpetuate that sameness.’ John Adams, the second American

president declared that British and Americans must together ‘force their

language into general use, in spite of all the obstacles that may be thrown in

their way’. Washington Irving (1851) concluded that ‘any deviations on our part

from the best London usage will be liable to be considered as provincialism’.