How can lexis be organised?

We have already encountered some ways in which lexical items can be organised. We’ll explore a few other ways of doing it and see if these ways of organisation are related in any way.

Alphabetical

listing

Items in dictionaries and encyclopaedias are listed under headwords, with an entry or a mini article following each. Items are alphabetised or placed in alphabetical order. This is useful because it is largely unambiguous and readers can find items fairly easily.

Word class

We know that lexical items can be classified according to word class (or parts of speech) – nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, etc. – and most dictionaries give word class labels to lexical items as a matter of course. Apart from getting information about use, we also need to be aware of word class for spelling, to distinguish between nouns (eg licence, practice) and verbs (eg license, practise).

Within this, we can also make distinctions between grammatical words and lexical words.

Frequency

We also regularly make distinctions between common words and obscure words. With lots of texts that have now been collected in corpora (this is the plural form of the singular corpus, meaning ‘body’ or ‘collection’), it has been possible to group lexical items into frequency bands. We noted earlier that the Collins Cobuild Dictionary groups items into five frequency bands. Items in the five bands make up 95% of all spoken and written English.

- BAND 1. Many of the words in this band are the common grammar words such as the, and, of and to, which are an essential part of the way we put things together. Also in this band are the very frequency vocabulary items, such as like, go, paper, return and so on. There are approximately 700 words in this band.

- BAND 2. This band includes words such as argue, bridge, danger, female, obvious and sea. There are approximately 1,200 words in this band. Bands 1 and 2 together account for about 75% of all English usage.

- BAND 3. This band includes words such as aggressive, medicine and tactic. There are approximately 1,500 words in this band.

- BAND 4. This band includes words such as accuracy, duration, miserable, puzzle and rope. There are approximately 3,200 words in this words in this band.

- BAND 5. This band includes words such as abundant, crossroads, fearless and missionary. There are approximately 8,100 words in this band.

- UNBANDED. The rest of the items (about 5% of English lexical items) are unbanded; examples include buccaneer, conflagration, epilogue, joust and progeny.

Grouping by

‘acquisition level’ for graded reading

Language teachers also often find it helpful to have

‘controlled vocabulary’ in the language readers. This is known as the

‘vocabulary control movement’, and very well known listing is Michael West’s A

General Service List, published in 1953. West himself taught English in

West’s list is aimed at second- or foreign-language learners of English. We can also think about how first-language or mother-tongue learners of English might acquire some lexical items first and others later in more formal educational settings.

Lexical fields

If you have consulted a thesaurus before, you will be aware of how vocabulary can be grouped according to its semantic or lexical field, such as military ranks, colour terms, emotions or birds. (You can browse around the following on-line Thesaurus site, based on Roget’s well-known version: http://www.thesaurus.com/.) These theories attempt to provide systems based on general-particular and part-whole relationships. An example of a general-particular system would be the system based on vehicles (the lexical field), which would include particular vehicles like car (and more specifically saloon/sedan, estate car/station-wagon, coupé, hatchback, convertible, four-wheel drive, etc.), lorry, van, train, tram, van and so on. An example of a part-whole system would be the system based on car which would include part of a car like wing/fender, bumper, windscreen/windshield, boot/trunk, bonnet/hood, steering wheel, dashboard, tyre, etc.

Associative fields

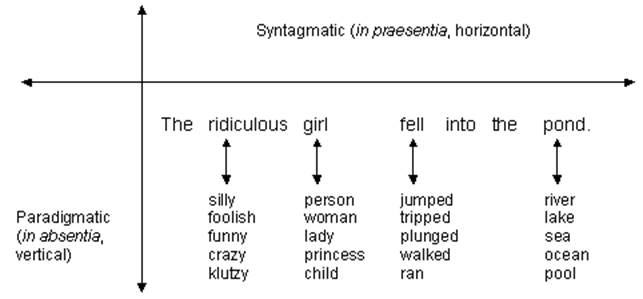

The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure made a distinction between associative relations and syntagmatic relations. We tend to use the term paradigmatic relations instead of associative relations today.

The paradigmatic relation is to do with choice. When you form a sentence, you need to (consciously or unconsciously) make a lexical selection at different points in the sentence. In the sentence above, for example, by choosing girl, you’d have rejected other possibilities like person or child. Language use therefore involves lexical choice. The items girl, person and child have a relationship in absentia because by choosing one, the others will be absent.

But girl doesn’t only relate to person, child and so on; it relates to the, ridiculous, fell and so on. It relates to the items that are present. This is the syntagmatic relation, or the relations in praesentia since they items co-occur with girl.

Others

You can probably also think about other ways of organising the lexicon: on the levels of formality (very formal, formal, neutral, informal, very colloquial), on the level of specialisation or technicality, on the level of geography (eg British v American items like spanner v wrench), on the source of the items.

Core vocabulary

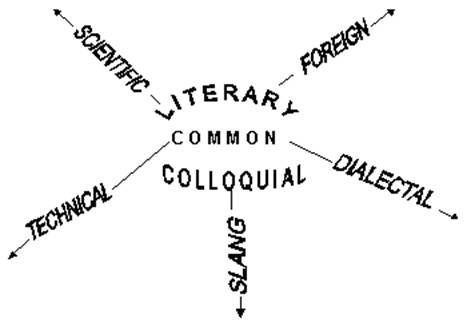

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) provides the following diagram to characterise English vocabulary as seen by the compilers/editors of the dictionary.

Here is their explanation of the diagram.

The

centre is occupied by the ‘common’ words, in which literary and colloquial

usage meet. ‘Scientific’ and ‘foreign’ words enter the common language mainly

through literature; ‘slang’ words ascend through colloquial use; the ‘technical’

terms of crafts and processes, and the ‘dialect’ words, blend with the common

language both in speech and literature. Slang also touches on one side of the

technical terminology of trades and occupations, as in ‘nautical slang’,

‘Public School slang’, ‘the slang of the Stock Exchange’, and on another passes

into true dialect. Dialects similarly pass into foreign languages. Scientific

terminology passes on one side into purely foreign words, on another it blends

with the technical vocabulary of art and manufactures. It is not possible to

fix the point at which the ‘English Language’ stops, along any of these

diverging lines.

They

suggest that it is not clear where a word ceases to be part of the English

language as there are different levels of technicality, foreignness, and so on.

An item like heart is core and should be located in the centre of the

diagram, whereas an item like cordial is probably more literary (more

likely to be written than spoken), whereas an item like cardiac is more

scientific (and perhaps more technical as well). If you refer to your heart as

your ticker, you have chosen a more colloquial or slangy term.

They

suggest that it is not clear where a word ceases to be part of the English

language as there are different levels of technicality, foreignness, and so on.

An item like heart is core and should be located in the centre of the

diagram, whereas an item like cordial is probably more literary (more

likely to be written than spoken), whereas an item like cardiac is more

scientific (and perhaps more technical as well). If you refer to your heart as

your ticker, you have chosen a more colloquial or slangy term.

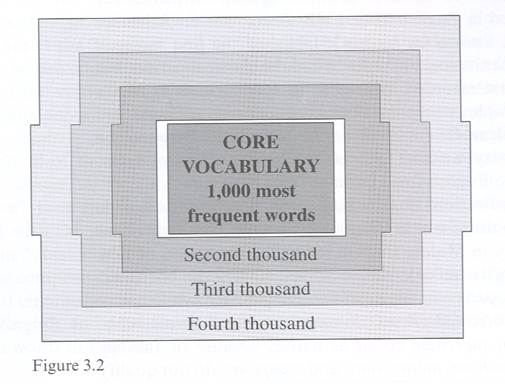

Stockwell and Minkova (2001) represent the core-periphery distribution in terms of deciles, but with potentially more layers being potentially added (see Figure 3.2 above). They also give statistical correlation between each decide and source of words.

Sources of the most

frequent 10,000 words of English

|

Decile |

English |

French |

Latin |

Norse |

Other |

|

1 |

83% |

11% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

|

2 |

34 |

46 |

11 |

2 |

7 |

|

3 |

29 |

46 |

14 |

1 |

10 |

|

4 |

27 |

45 |

17 |

1 |

10 |

|

5 |

27 |

47 |

17 |

1 |

8 |

|

6 |

27 |

42 |

19 |

2 |

10 |

|

7 |

23 |

45 |

17 |

2 |

13 |

|

8 |

26 |

41 |

18 |

2 |

13 |

|

9 |

25 |

41 |

17 |

2 |

15 |

|

10 |

25 |

42 |

18 |

1 |

14 |

The notion of ‘core vocabulary’ seems to combine a number of the categories that we mentioned earlier in that:

- core items are more frequently used;

- core items are likely to be acquired earlier by learners, particularly first-language learners;

- core items associate easily with other items because they are not specialised (scientific, technical, etc.) – you can probably use hearty with a lot of other items (welcome, soup, speech, meal, person, laugh, etc.), but most of us would only combine cardiac with failure or arrest

- because core items are not specialised and not used only in particular contexts, they can take on many different levels of meaning – you can use heart to refer to the organ (as in ‘heart transplant’), or the shape (‘he drew hearts on the card’, ‘the Queen of Hearts’), or to refer to passion or compassion (‘have a heart!’, ‘my heart wasn’t in it’) or the mind (‘the heart of man is capable of villainy’) or courage (‘don’t lose heart’), or metaphorically to the essence or core of something (‘the heart of the matter’); it might be used in set phrases like learn by heart (‘memorise’), eat your heart out (‘eat violently (in jealousy)’), heart-to-heart talk (‘sincere conversation’)

Examine the following sentences from Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield. The narrator is the adult David Copperfield and he describes himself as a child.

He asked me if it would suit my convenience to have the light put out; and on my answering ‘yes’, instantly extinguished it.

I

… went upstairs with my candle directly. It appeared to my childish fancy, as I

ascended to the bedroom …

You might notice the core item put out contrasted to the non-core item extinguished in the first sentence; similarly, went upstairs (core) contrasts with ascended (non-core) in the second sentence. The core items suggest identification with the child (because children learn core items first), and the non-core items suggests a distancing from the child as the narrator employs the literary norms lexically.

D. The

sources of English words

E.

Vocabulary across text types