Shakespeare’s

English

Shakespeare wrote 400 years ago. His English was obviously different from ours. His works are easily available, though most printed editions of Shakespeare have undergone some form of editing. Here are just some quick notes as you explore his language.

Folio and

quarto?

Shakespeare scholars might refer to the quarto or folio editions of the plays. During Shakespeare’s lifetime, some of his plays were printed. These would be individual plays in small volumes and it is these that are called the quartos.[1] (Some of them were authorised texts, sold to printers particularly when the theatres were closed because of the plague. These are the good quartos. Some, however, were unauthorised ones and contained many inaccuracies: the bad quartos.): Shakespeare’s complete works were published in a bigger folio[2] volume in 1623.

If we are interested in looking at Shakespeare’s English in a relatively undisturbed condition, we’ll need to look at the (good) quarto and folio editions. Fortunately, we needn’t go to fusty libraries and pore over old facsimiles. The quarto and folio editions are available on the web: try going to http://web.uvic.ca/shakespeare/.

Orthography

![]() Once

you start looking at the folio and quarto texts in their unedited form, it will

be clear that the spelling and punctuation can be inconsistent and differs from

what we are familiar with today. For example, <u> might be used for our

<v> and vice versa. (The explanation for this is that <u> and

<v> were seen as different forms [allographs]

of the same letter [grapheme]; the

rule was that you used <v> at the start of a word, and <u>

elsewhere. Therefore <u/v> could represent a vowel or consonant sound.) Similarly, <i>

and <j> might also be used interchangeably (because <j> was

considered a decorative version of <i>;

therefore <i/j> could represent a vowel sound

or consonant sound). If you consult facsimiles of Shakespeare, you’ll also see

the ‘long s’ (see the top right of this paragraph). This looks very much like

an <f> only that the cross bar does not extend to the right of the line,

as in the box on the right.

Once

you start looking at the folio and quarto texts in their unedited form, it will

be clear that the spelling and punctuation can be inconsistent and differs from

what we are familiar with today. For example, <u> might be used for our

<v> and vice versa. (The explanation for this is that <u> and

<v> were seen as different forms [allographs]

of the same letter [grapheme]; the

rule was that you used <v> at the start of a word, and <u>

elsewhere. Therefore <u/v> could represent a vowel or consonant sound.) Similarly, <i>

and <j> might also be used interchangeably (because <j> was

considered a decorative version of <i>;

therefore <i/j> could represent a vowel sound

or consonant sound). If you consult facsimiles of Shakespeare, you’ll also see

the ‘long s’ (see the top right of this paragraph). This looks very much like

an <f> only that the cross bar does not extend to the right of the line,

as in the box on the right. ![]() Generally the ‘short s’ (our normal <s>) is found only

in word-final position. Spelling can be notoriously inconsistent, sometimes to

do with the amount of space available on a particular line or page.

Generally the ‘short s’ (our normal <s>) is found only

in word-final position. Spelling can be notoriously inconsistent, sometimes to

do with the amount of space available on a particular line or page.

Italicisation is normal for proper nouns. Many words also attract additional final e’s. (Don’t assume that these are pronounced though.) The apostrophe is generally used to indicate ellipsis and not for the possessive.

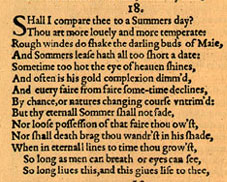

Examine

the facsimile of the well-known Sonnet 18 on the left. Notice the lack of

consistency with ‘Summers’ (line 1) and ‘Sommer(s)’ (lines 4 and 9). Note also the long s’s in the words shake,

shot, shines, shall, loose, possession, ow’st, shall, shade, grow’st, see. The apostrophe is used freely in

words like dimm’d

and ow’st

to indicate that the pronunciations are [dImd] and

[oUst]

rather than [dImId]

and [oUIst].

Note also that the apostrophe is not

used for the possessive: therefore Summers day and Sommers leafe rather

than Summer’s day and Summer’s leaf.

Examine

the facsimile of the well-known Sonnet 18 on the left. Notice the lack of

consistency with ‘Summers’ (line 1) and ‘Sommer(s)’ (lines 4 and 9). Note also the long s’s in the words shake,

shot, shines, shall, loose, possession, ow’st, shall, shade, grow’st, see. The apostrophe is used freely in

words like dimm’d

and ow’st

to indicate that the pronunciations are [dImd] and

[oUst]

rather than [dImId]

and [oUIst].

Note also that the apostrophe is not

used for the possessive: therefore Summers day and Sommers leafe rather

than Summer’s day and Summer’s leaf.

Pronunciation

Remember that the Great Vowel Shift is still in progress in the time of Shakespeare, so that the long vowel sounds might be different from what we are used to today. Shakespeare’s English would also have been rhotic.

Sometimes, words are stressed differently (eg reVENue rather than REVenue as today). Contractions are used fairly freely and there is a preference for proclitic contractions (such as ’tis, ’twill or ’twas) rather than enclitic contractions (preferred today, such as it’s, it’ll). (A proclitic word is so weakened that it sounds as if it is attached to the following word; an enclitic word is so weakened that it sounds as if it is attached to the preceding word.)

In recent years, there has been an interest in putting on Shakespeare using Original Pronunciation (OP), and the contribution of linguist David Crystal has been significant. Explore his website for his book Pronouncing Shakespeare: http://www.pronouncingshakespeare.com/ There are some recordings in that website.

The Open University has a 10-minute video on this: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gPlpphT7n9s

Crystal’s son Ben Crystal demonstrates OP with Sonnet 116 here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bt7OynPUIY8

Pronouns

Remember also that the you and thou distinction is important. (We have discussed this elsewhere.) Case distinctions are observed for thou; therefore:

- thou seest all (subject form, with the appropriately inflected verb, usually -st)

- he followed thee (object form)

- we went into thy garden; give us thine opinion (possessive adjective; thine before a vowel)

- she is thine (possessive pronoun)

- give thyself a fitting reward (reflexive pronoun)

However, the you and ye distinctions were more fluid; the possessive forms are of course your and yours.

Today, we usually omit the pronoun in commands (the imperative mood), as in ‘Come here!’, ‘Believe me’, ‘See this’. In Shakespeare’s English, the pronoun could be inserted if desired: ‘Come thou hither!’, ‘Believe ye me’, ‘See thou this’.

Grammar

Verbal inflexions

In the third person singular (indicative mood), verbs might alternate between the more northern -s and the more southern -th inflexions (eg ‘She comes’ and ‘She cometh’; ‘he has’ and ‘he hath’). The inflexion for the second person (indicative mood) – -st as comest, desirest, hast, wouldst – has been mentioned earlier. Note that a [@] or [I] sound might or might not be inserted before -s, -st, -th or -d (the past tense): the contrast is often shown through the spelling, as in calles, callest, called as opposed to calls, callst, call’d. Some of the past tense and past participial forms might also be different from that in PDE.

Past tense and past

participial forms of verbs

By and large, the past tense and past participial forms of verbs are close to the system in PDE. Today we have verbs that take on ‘strong forms’ (irregular: sing-sang-sung, wake-woke-woken) or ‘weak forms’ (regular: like-liked-liked, jump-jumped-jumped) Sometimes, Shakespeare might alternate between different forms, and the past tense and past participial forms might be switched. He uses both caught (strong form) and catched (weak form); built (s) and builded (w); holped/holpen (s) and helped (w)

The operator

‘do’

The operator ‘do’ could be used not to suggest emphasis as in today’s English (‘I like you’ v. ‘I do like you’). This is sometimes known as the periphrastic use of ‘do’.

Questions

Similarly, questions could be formed either with the operator ‘do’ or without: ‘Like I you?’ v. ‘Do I like you?’; ‘Where goest thou?’ v. ‘Where dost thou go?’ In PDE, the version with the operator ‘do’ is obligatory unless there are other modal verbs.

Negation

And similarly, negatives could be formed either with the operator ‘do’ or without: ‘I like you not’ v. ‘I do not like you’. In PDE, the version with the operator ‘do’ is obligatory unless there are other modal verbs.

The subjunctive

The subjunctive is used in PDE in some formulaic constructions like ‘God save the queen!’, ‘God bless you’, ‘suffice it to say’. Note that the verb does not appear to agree with the subject (not ‘God saves the queen’ or ‘God blesses you’). In these examples, they express wishes or prayers. It is also used in some constructions to denote a hypothetical (imaginary) situation, such as ‘if I were rich man’, ‘if she were alive today’ (this is the past subjunctive; in these examples inversion is possible: ‘were I a rich man’, ‘were she alive today’). It is also used in some clauses that indicate demands or requirements: ‘I request that the prisoner come forward’, ‘It is necessary that we be informed of the facts’.

All these constructions were available to Shakespeare, but the subjunctive was used more extensively. For example, most if clauses would contain the subjunctive. Therefore, you will see, ‘If it please you’ (rather than pleases), ‘if this be error’. Even today, we might say ‘if need be’ (be here means exist, and therefore it means ‘if need exists’ or, more idiomatically, ‘if there is a need’).

The Progressive

You might notice that the progressive (‘continuous’) is hardly used in Shakespeare. In a study of the progressives,[3] Elness examined the English used in three periods: I (1500–1570), II (1570–1640) and III (1640–1710). The relative frequencies (per 1,000,000 words) rose steadily from 173.5 in period I, through 274.0 in period II, to 584.7 in period III.

For details, you are invited to read the following selectively.

The perfective

The auxiliary verb used for the perfective can be different from the PDE version. Today, the auxiliary verb is have. In Shakespeare’s English, intransitive verbs of motion (come, go) would take on the verb be to form the perfective aspect. (This roughly follows the pattern in French and German.) Peter Quince in A Midsummer Night’s Dream says: ‘Have you sent to Bottom's house? is he come home yet?’; today, we would say ‘has he come home yet?’ This survived till the 19th century, so that Charlotte Brontë wrote in Jane Eyre (1847): ‘I am come to a strange pass: I have heavy troubles’. Today we would write ‘I have come’ rather than ‘I am come’.

Comparative and superlative forms

Shakespeare might use the ‘double’ comparative and superlative (‘most unkindest cut of all’, ‘most boldest and best hearts of Rome’) or he might use the –er and –est forms where we expect more or most or the other way round (‘more tall’, ‘anxiouser’, ‘nothing certainer’, ‘ beautifullest’).

Vocabulary

There are of course numerous vocabulary differences. Just inspect the glossaries of any volume of the collected works of Shakespeare.

Blake, Norman (2002), A grammar of Shakespeare’s language (Houndmills: Macmillan)

Busse, Ulrich (2002), Linguistic variation in the Shakespeare corpus: morpho-syntactic variability of second person pronouns (Amsterdam: Benjamins)

Johnson, Keith (2013), Shakespeare’s English: A Practical Guide (London: Pearson)

Salmon, Vivian and Edwina Burness (eds) (1987), A reader in the language of Shakespearean drama (Amsterdam: Benjamins) [Call No. P140 Ahl35]