EL1102 Studying English in Context

Lecture No. 5 (Part 2)

An

aside about conversation

·

Chomsky’s

distinction between competence and performance

·

Linguistic competence

= the internalised knowledge users of a language supposedly have about its

system

·

Chomsky saw

performance as secondary to competence: what we do when we actually speak, ie,

the process of speaking and writing.)

·

Conversation

contains many performance errors (he sees real language use as being often

‘limited’ and ‘degenerate’)?

Performance

and competence

·

Saussure has roughly

equivalent terms in French: la langue and la parole

·

Saussure: la

langue = system of communication produced by a speech community; la

parole = specific verbal behaviour of individuals in speaking and writing.

·

While it is true

that there is lack of fluency in speech because of the lack of planning time,

this doesn’t quite capture all there is in conversation.

Casual

English conversation in Singapore

·

In Singapore, we

know that casual conversation is taking place when the colloquial (as opposed

to the standard) variety of Singaporean English is used.

·

Consider the

following possibilities:

o

Eh, fall down got

pain or not ha? (CSE: use of Singaporean exclamations and pragmatic

particles to emphasise interpersonal elements, parataxis)

o

Aiyo, yesterday you

fall down ah. Got pain or not one. (CSE)

CSE v

Standard SE

Compare this with

some other possibilities

·

Oh poor thing, I

heard about you falling down; did it hurt? (informal Standard Singaporean,

etc. English [StdE]: parataxis)

·

Did it hurt much

when you fell down yesterday? (StdE: hypotaxis)

·

I hope your fall on

the pavement yesterday did not cause undue pain. (StdE, formal, explicit,

nominalisations in bold)

How can we tell the

difference between CSE and SSE?

·

CSE employs

pragmatic particles (lah, meh, lor, hor, ah, etc.)

·

Verb inflexions are

optional in CSE (He come here everyday one, Last time we never

watch TV)

·

Noun inflexions are

optional in CSE (You go to por-por house or not? You want so many cat

for what?)

·

Complex verb phrases

cannot usually be found in CSE

·

The question form is

different (Is he coming? [SSE] v. He coming ah? or He coming

or not? (CSE)]

·

Conditions/threats

in CSE can be expressed without if, when, etc. (You say that

again I tell your mother [CSE] v. If you say that again, I will tell

your mother)

·

The verb be

(is, are, was, were, etc.) is often not found in CSE (Por-por coming; You

think you so smart)

Diglossia

·

The terms CSE v

SSE assumes an analysis of English in Singapore as being diglossic

·

The term diglossia

was introduced by the linguist Charles Ferguson in 1959 to refer to how ‘in many speech communities two or more varieties of

the same language are used by some speakers under different conditions’.

·

The variety used for

writing, and in more formal situations is known as the High or H variety

·

The variety used

informally in speech is the Low or L variety

·

For example, in

Arabic-speaking communities, people usually use the local version of Arabic

(Colloquial Arabic, the L variety) at home; but when these same people delivery

a lecture at university, or give a sermon in a mosque, or write a letter, they

use Standard Arabic (or Classical Arabic, the H variety).

·

Many Singaporean

speakers of English might therefore switch from Standard Singaporean English

(SSE, the H variety) to CSE (the L variety) in conversational situations.

·

This kind of

analysis does not take into account people who are uncomfortable with the

English language in Singapore

Personalisation

·

Conversation is

usually used to develop relationships rather than to merely convey

information

·

The norm is to be involved

rather than be detached

·

The norm is to be emotional

and subjective rather than neutral

·

This comes through

in the lexis and the grammar.

Showing personalisation in our language 1

·

Use appraisal:

this refers to attitudinal colouring (including certainty, emotional response,

social evaluation and intensity)

·

The woman was

beautiful/competent/disappointed

·

The woman was really

really beautiful/seemed a bit disappointed sort of/kind of

competent.

Showing personalisation in our language 2

·

Show involvement:

this refers to how interpersonal worlds are shared by speakers (use of

vocatives, slang, anti-language, expletives and taboo words) (anti-language =

language that creates new terms in addition to available ones, eg

criminal slang)

·

slang/taboo/expletives:

bloody shitty fucking

·

vocatives: Seng,

Ah Seng, Seng-Seng, Dear, Darling

Showing

personalisation in our language 3

·

Use humour:

solidarity is created through humour and teasing/banter

·

D: what I mean is

sex education of a decent KIND [look of mock anger]

Border-crossing

Is

‘conversation’ a ‘closed’ genre or social variety? Border-crossing describes

how ‘conversational English’ might migrate to other situations. Other varieties

might therefore imitate the features of conversation.

Forces at work

The British linguist Norman

Fairclough (pronounce: FAIR-cluff) focuses on the following forces at work:

(a) Informalisation

(the media, government, etc. are using more informal styles)

(b) Marketisation

(English texts are becoming increasingly ‘market-oriented’ or ‘marketised’)

The breaking-down of some genres

The breaking-down of some genres

This suggest that some of the comments made about text-types being

different from each other might be breaking down. The conversational style, in

particular, has been imitated in other genres because of some of the

positive associations with conversation (friendliness, approachability,

sincerity). We can call this conversationalisation.

Conversationalisation in adverts

The British linguist Geoffrey Leech who studied

the language of advertising noted there was a ‘public-colloquial’ style of

advertising. Advertisements can use language associated with the private sphere

to give an impression of personalisation.

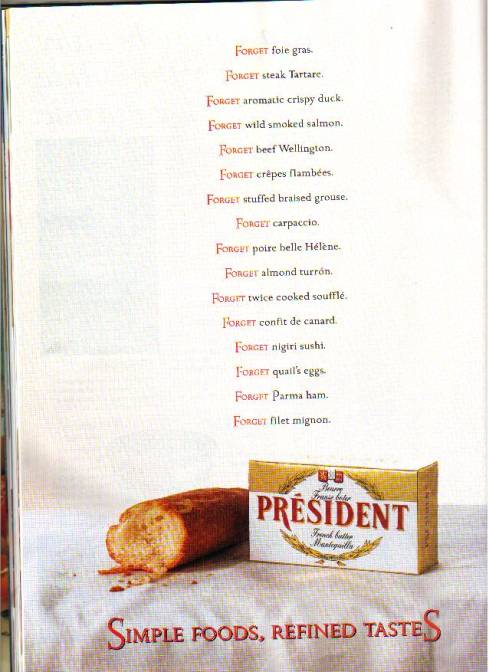

Advert: Example 1 (left)

·

A repetitious use of

the commanding speech function.

·

‘Forget’ (a core

item) is juxtaposed with more peripheral items.

·

A lot is assumed,

rather than stated explicitly.

·

Short, punchy

clauses.

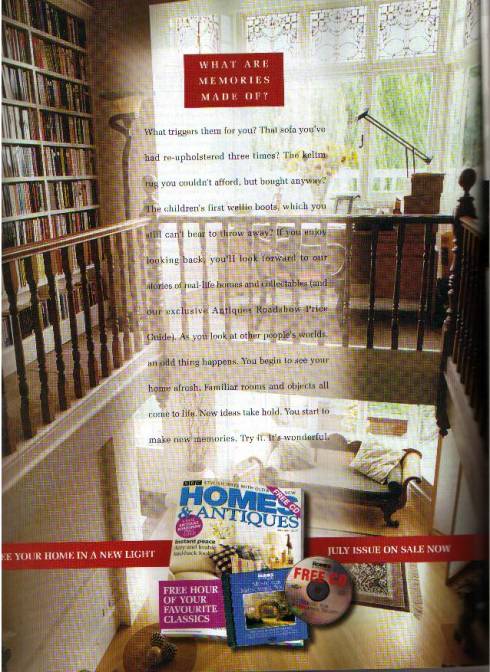

Advert: Example 2

The text in the middle of the page reads: ‘WHAT

ARE MEMORIES MADE OF? What triggers them off for you? That sofa you’ve had

re-upholstered three times? The kelim rug you couldn’t afford, but bought

anyway? The children’s first wellie boots, which you still can’t bear to throw

away? If you enjoy looking back, you’ll look forward to our stories of

real-life homes and collectables (and our exclusive Antiques Roadshow Price

Guide). As you look at other people’s worlds, an odd thing happens. You begin

to see your home afresh. Familiar rooms and objects all come to life. New ideas

take hold. You start to make new memories. Try it. It’s wonderful.’

·

Speech functions? Questioning

used a lot at the beginning. Commanding used near the end ‘Try it’.

·

Use of appraisal and

personalisation: ‘It’s wonderful.’

·

Short clauses

·

‘You’ used very

often

·

Core lexis

(including informal items ‘wellie boots’ [rather than ‘Wellington boots’]

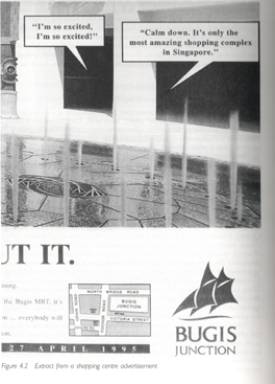

Advert: Example 3

The text boxes read:

‘I’m so excited, I’m so excited!’

‘I’m so excited, I’m so excited!’

‘Calm down. It’s only the most amazing shopping complex in Singapore’

The opening of Bugis junction.

Are the readers supposed to imagine the voices, or ‘become’ those people

themselves in their imagination?

Clearly a high degree of personalisation (expressive lexis).

Use of command function.

Synthetic personalisation

Fairclough (pronounced FAIR-cluff) calls

this synthetic personalisation because of course advertisements are not

addressed to you personally; they only attempt to give that impression - ie

this is manipulative. Others call it ‘fake intimacy’ and a ‘phoney sense of

belonging’. Fairclough labels all of this conversationalisation.

Fairclough’s definition of conversationalisation

Conversationalisation

involves a restructuring of the boundary between public and private orders of

discourse – a highly unstable boundary in contemporary society characterised by

ongoing tension and change. Conversationalisation is also consequently partly

to do with shifting boundaries between written and spoken discourse practices,

and a rising prestige and status for spoken language which partly reverses the

main direction of evolution of modern orders of discourse ….

Conversationalisation includes colloquial vocabulary; phonic, prosodic and

paralinguistic features of colloquial language including questions of accent;

modes of grammatical complexity characteristic of colloquial spoken language …;

colloquial modes of topical development …; colloquial genres, such as

conversational narrative. (Fairclough 1994: 260)

Example: Newspaper headlines

The news story about the economic recovery in

Singapore is given the headline ‘Sun’s up and looking good’ (New Paper,

18/11/1999). There is grammatical ellipsis associated with conversation (cf. ‘The

sun is up and things are looking good’), and the lexis is core with a high

evaluative element.

Example: Radio DJs

JA: It’s

the Morning Express, Joe and the Flying Dutchman, oh by the way, word just in.

FD: What?

JA: Apparently,

what Divine Brown and Hugh Grant were doing as well?

FD: Yes?

JA: Ah,

wasn’t sex.

FD: No,

no!

JA: Wasn’t.

FD: No,

oh!

JA: Yah.

FD: Really?

JA: Just,

just thought I’d share that with you.

This was broadcast in 1998 during the enquiry about

the American president Bill Clinton. He justified his denial of his having had

sex with Monica Lewinsky because he only engaged in oral sex with her, and this

did not constitute ‘sex’ in the strict sense of the word. There is also

allusion to the British actor Hugh Grant having been arrested 1995 for getting

a prostitute, Divine Brown, to perform oral sex on him in a car. All of this is

alluded to in the ‘conversation’, but never made explicit, as is typical in

conversation. Note also the discourse marker oh by the way, the high degree

of ellipsis, and general use of core lexis.

Example: Academic Writing

It is generally true that law courts (at least in Britain) exhibit an

extreme reluctance to take account of anything other than the dictionary

meaning of particular expressions. A particular source of irritation to me is

the use of so-called ‘expert witnesses’ in legal cases involving the use of

obscene or abusive (often racist) language. In such cases the defence

invariably bring in to court some cobwebby philologist who will testify, for

example, that to shout Bollocks! Is not offensive because it ‘means’

little balls. It seems that the only linguistic evidence admissible in these

cases is the etymology of a word or phrase (and frequently the ‘etymology’ is

wholly spurious) – no account is taken of the circumstances in which the word

is used nor of the speaker’s intention in uttering it. In another court case,

the defendant was charged with four offences against the owner of a Chinese

restaurant. One was that he had called the restaurant owner a Chinky bastard,

but this charge was dismissed because an ‘expert’ testified that the expression

‘meant’ ‘wandering parentless child travelling through the countryside the

Ching Dynasty’ and was in no way offensive. Courts seem incapable of taking on

board the fact that the original lexical meaning of an expression is not a good

guide to the speaker’s intention in employing that expression.

(Jenny Thomas, Meaning in Interaction 1995, p. 17)

Fairclough sees conversationalisation as part of commodification

because it manipulates people for institutional purposes, and he is therefore

ambivalent about how we should react to this phenomenon. How do you react to

this yourself?

Back to Part 1 of the lecture

Back to EL1102 Home Page

Back to EL1102 Lecture Schedule

Click here to go to Tutorial No. 4, based on this

topic.

Email

Peter Tan (for comments and questions)

© 2001 Peter Tan