The Old English period

We have reached roughly the half-way mark of this module. In the earlier bits, we focused mainly on describing some of the changes that have occurred in the English language in terms of writing, pronunciation, lexis and grammar (the internal history of the language). It is possible to describe and account for change without making reference to the the speakers or the events that surround the speakers, but we feel that this will only provide only part of the picture. The rest of the module will take on a more sociolinguistic focus on the history of English (and refer more to the external history).

An American scholar, Salikoko Mufwene prefers to talk about the ecology of language evolution (that, in fact, is the title of his book, published by Cambridge University Press in 2001). The word ecology, normally used today in relation to biological studies is to do with the reciprocal relations between organisms and their environment. When we talk about language ecology or linguistic ecology, therefore, we mean that we need to consider language not as an abstraction, but language as a living entity spoken by real users with real needs, living in particular cultural, economic, social, religious and other contexts. To understand why languages evolved – whether there has been language change (ie the same language has developed new lexis, structures, etc.) or whether there has been language shift (ie a particular community changes the repertoire of language(s) being spoken) or whether there has been a functional shift between languages (ie in multilingual situations, different languages might be associated with different social contexts and situations, and the prestige of each variety of language might change) – we need to appreciate the outer context.

This is not as arcane as it might sound here. Many of the forces at work in the past are still at work here, and examining the history of English in this light might make us more aware of the forces at work today and appreciate how linguistic issues relate to a range of other issues.

At this point now, we are ready to

discuss some aspects of the external history of English and we can relate some

of it to the internal history. Please consult the time

chart. Because we will discuss the external history, I will give a

quick sketch of the salient events through a series of maps. Our main interest

will be in the relationship between the external history and the

language. As an alternative, go to the BBC Online website of the Radio 4

programme The Routes of English, which contains a section entitled ‘The

World of English’: http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/routesofenglish/world/index_noflash.shtml

– this includes a timeline for the history of English and gives the points in a

nutshell.

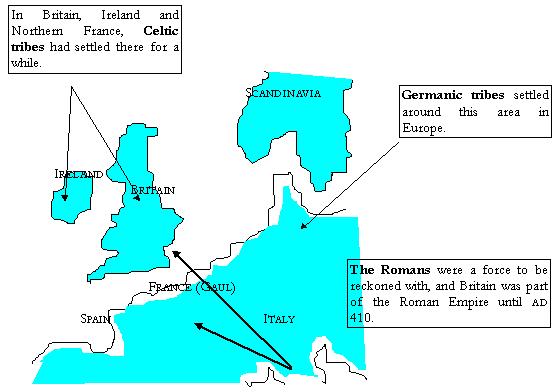

Phase 1. Pre-English Days (AD 1–450)

Notice that there was no such thing

as ‘English’ during this period. The inhabitants of

This

was also the time when the

This

was also the time when the

(Please note that

during this period, it is meaningless to talk about ‘

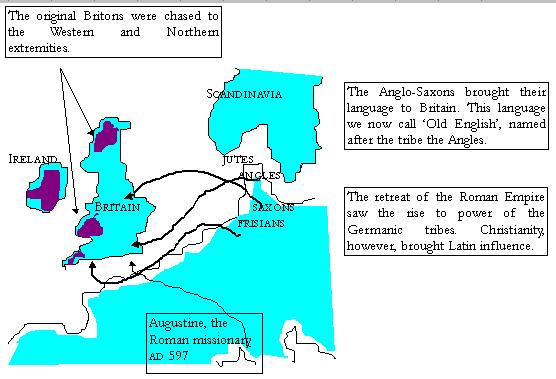

Phase 2. Anglo-Saxon invasions and consolidation in

The OE extract from the Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle tells us that the Romans faced many problems from attacks by various

tribes, including the Huns. In 410, the last of the Roman legions left

The tribes that

set up their kingdoms in

(There is a question mark over the status of the Jutes and whether they can be associated with the Jutland peninsula. There are theories of them being from south of the Saxons or from southern Sweden. We also know very little about the language they spoke.)

Latin texts of the

time used the terms Angli and

By and large, they

were well-known for their military prowess, and not for their sophisticated

culture. They were concerned with ordinary day-to-day living, and there was a

lot of in-fighting until they were united by King Alfred the Great (871–899).

As a result of this a standard began to be developed based on the

Two important puzzles remain though.

(a) If the Germanics maintained their language in a new land, how is it that there isn’t more evidence of contact through borrowing from the original Celtic languages?

Loreto Todd in an article in English Today puzzles over this. (For copyright reasons, the article is not on the website, but is available to registered students from the Workbin in IVLE.)

(b) Why is it that the Germanics

were able to maintain their language in

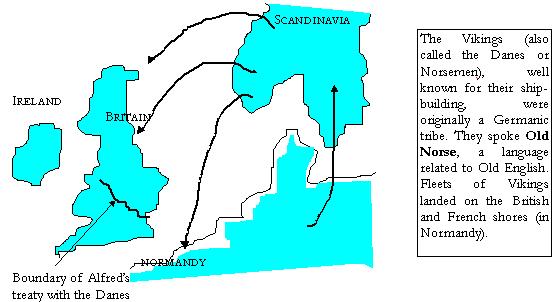

Phase 3. Scandinavian invasions (787 onwards)

The

Scandinavian attacks on

The

Scandinavian attacks on

The Scandinavians

raided towns and monasteries; they captured towns and cities and then proceeded

to settle in these places. The army of Alfred the Great resisted them for seven

years before taking refuge in the marshes of

This, however, was

not the end of the battles. There were more Scandinavian attacks later on, and

in the new millennium,

After taking over the land, the Scandinavians often lived peaceably with the English, and there were many intermarriages. They adopted English customs, and the English accepted them. More important for our purposes, however, is the language contact situation resulting in the English language accepting Old Norse (ON) words and forms. For example, the personal pronouns they, them and their come from ON. So does the 3rd person inflexion for verbs –s. Words that are borrowed from ON include anger, cake, egg, loan, root, skirt, steak, take and window. There was no obvious centripetal or centrifugal force at work.

Many suggest that

the contact between OE and ON might have led to the loss of many

inflexions. Because the inflexions were different in OE and ON, they were often

unhelpful in conversation between OE and ON speakers. They suggest that

speakers might have deliberately not used the inflexions to facilitate

communication. In situations of intermarriage, the children might grow up

learning this ‘simplified’ version of English. Some would even say that the English

language had undergone a process of pidginisation

and creolisation.

When you’re

ready to take the quiz based on this topic, go to the IVLE page and click on

‘Assessment’ on the left, and then on ‘Old English period’.