What is phonology?

1. Definitions

Phonology is that branch of linguistics which studies the sound system of languages. The sound system involves

- the actual pronunciation of words, which can be broken up into the smallest units of pronunciation, known as a segment or a phoneme. ( The words pat, chat and fat have different phonemes at the beginning, and so phonemes contrast with each other to produce different words.)

- prosody – pitch, loudness, tempo and rhythm – the ‘music’ of speech. (Other terms used are non-segmental phonology or supra-segmental phonology.)

We shall focus more on the former because there is very little information about historical prosody!

(It might also be relevant to say here that we will distinguish phonetics from phonology. The former concentrates on the actual sound-making and could be thought of as being more akin to physics; the latter concentrates on how sounds are organised in individual languages. In order to do phonology, therefore, you will necessarily need to know at least some of the phonetics.)

2.

The IPA

Phonologists and phoneticians generally

have to use special symbols – usually the IPA, or International Phonetic Alphabet.

This module does not attempt to teach you the IPA, although we will introduce you to the symbols used for English.

One word of warning: we said that English spelling was phonetic, more or less; we also said that English spelling sometimes represents morphemes as well. We need to careful, therefore, and not assume that every letter represents a phoneme. For example, people often talk about ‘dropping the g’ in words like talking and running (often written as talkin’ and runnin’), whereas <ng> in talking represents one sound /ŋ/, and <n’> in talkin’ represents another sound /n/; ‘dropping’ suggests that one sound has been left out.

Another convention that might be useful to mention here is that orthographic symbols (including spelling) are indicated by the use of angle brackets, as in <ch>; phonetic symbols are indicated by the use of square brackets, as in [k]; and phonemes are indicated by the use of oblique strokes, as in /k/.

You might like to go to the IPA interactive chart: https://www.ipachart.com/

(It might also be

useful to add that a number of American linguists use a modified version of the

IPA, so be forewarned if you have consulted or are consulting American texts.)

First of all, the letters b, d, f, h, k, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, v, w, z are given their conventional values as in normal English spelling.

Here are some other symbols for consonants with examples of the sounds (italicised) from English words. The alternative symbols have been included for information and will not be used in this module.

|

IPA Symbol |

Word |

Alternative Symbols |

|

IPA Symbol |

Word |

Alternative Symbols |

|

g |

get |

|

|

χ |

loch (Scottish) |

|

|

ʒ |

pleasure |

|

|

dʒ |

jam |

|

|

ʃ |

ship |

|

|

tʃ |

chin |

|

|

ŋ |

sing |

|

|

ʔ |

settle (Cockney) |

|

|

θ |

thin |

|

|

j |

yes |

y (American) |

|

ð |

this |

|

|

|

|

|

Here are some

vowel symbols. Vowels are different from consonants (here I am talking about sounds,

not spelling) in that there is relatively little obstruction to the air

passage. The kind of vowel sound that you produce will therefore depend on how

you adjust some of the movable organs that affect the sound produced –

especially your tongue position and whether you round (pucker) or spread your lips.

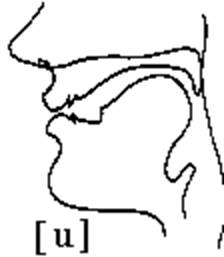

If you took an

x-ray picture of your oral cavity whilst saying particular vowel sounds, you

will notice that the tongue can be raised more or less (be in a close/high

or open/low position), and whether the raising is towards the front

(towards the lips) or the back (towards the throat).

|

|

|

|

|

[i] is the sound in tea; the tongue is

high (close), and raised in front |

[u] is the sound in two; the tongue is

high (close), and raised at the back |

[A] is the sound in tar; the tongue is

low (open), and raised at the back |

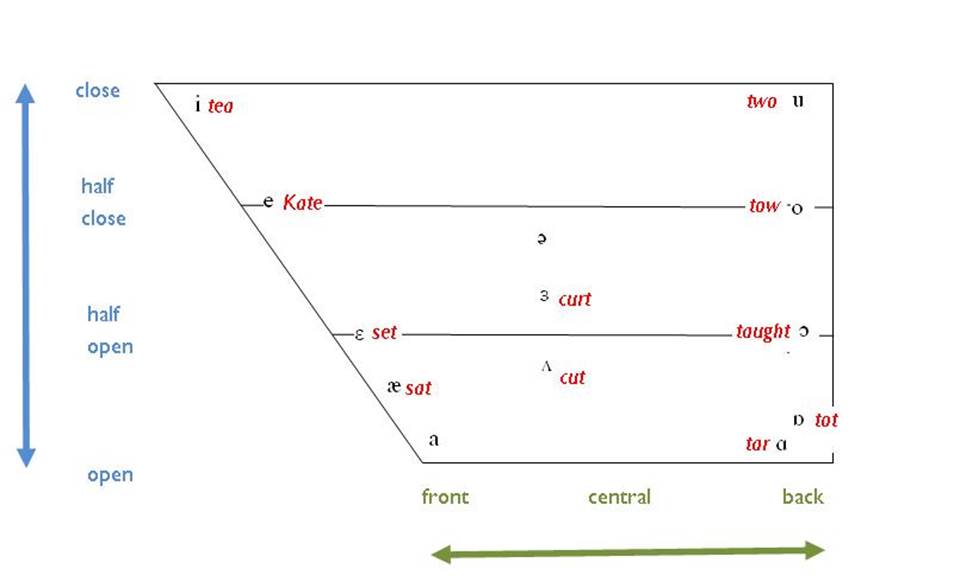

We can summarise

the information in a chart. I am aware that the chart is difficult to read, and

the examples of English words are also a little problematic given that there

are many accents of English today with therefore a range of different possible

pronunciations. (So, by ‘Kate’,

I mean the beginning of the vowel, because many people glide off to another

vowel. By ‘tow’ I mean the pure vowel sound as spoken by

the Scots, or the first part of the sound by others before the glide – but

again there are accents where this sound is not used. And there are many

accents that make a two-way distinction between taught, tot and tar; and indeed some which have the same vowel sound for all three.)

The words given

as examples of the sounds are based on southern British pronunciation or RP

(see below for a discussion of RP).

|

Pure Vowels |

|

Non-pure Vowels |

||||

|

IPA Symbol |

Key Word (Wells) |

Alternative Symbols |

|

IPA Symbol |

Key Word (Wells) |

Alternative Symbols |

|

ɑː |

start, palm |

|

|

aɪ |

price |

ɑɪ,

ʌɪ |

|

æ |

trap |

a |

|

ɔɪ |

choice |

|

|

ɔː |

thought |

|

|

eɪ |

face |

|

|

ɒ |

lot |

|

|

oʊ |

goat |

əʊ |

|

uː |

goose |

|

|

aʊ |

mouth |

ɑʊ |

|

ʊ |

foot |

|

|

ɪə |

near |

|

|

ʌ |

strut |

|

|

ʊə |

cure |

|

|

iː |

fleece |

|

|

aɪə |

diary |

ʌɪə |

|

ɪ |

kit |

|

|

aʊə |

hour |

|

|

ɛː |

square |

ɛə,

eə |

|

|

|

|

|

ɛ |

dress |

e |

|

|

|

|

|

ɜː |

nurse |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ə |

comma |

|

|

|

|

|

The keywords are

from John Christopher Wells’s Accents of

English: An introduction (1982). You can see the list here as well: http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/wells/phoneticsymbolsforenglish.htm

3.

Range of accents

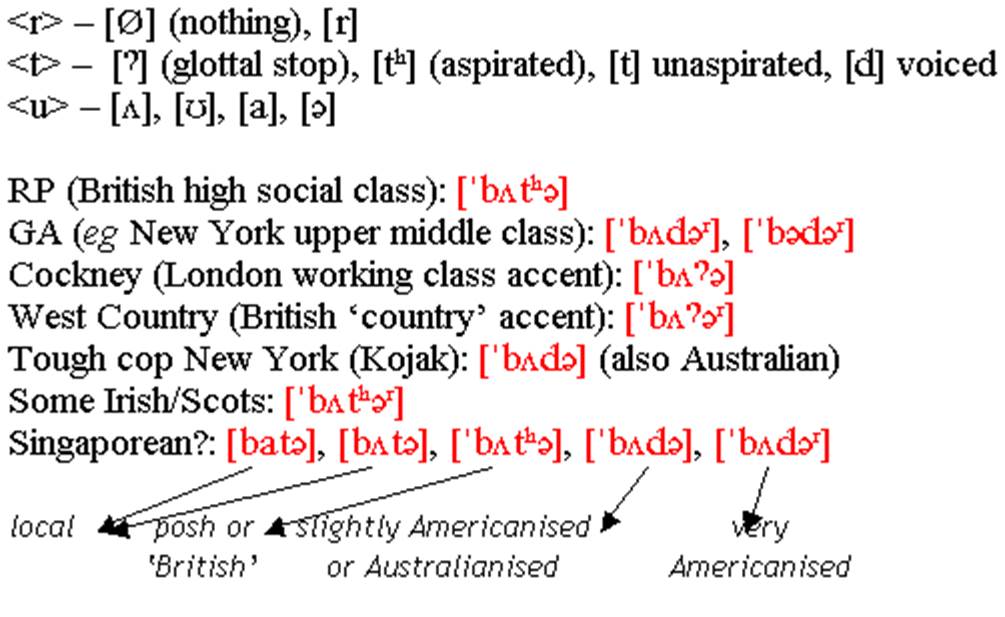

We use the term ‘accents’ (as opposed to ‘dialects’) to refer to differences in pronunciations. The standardised English spelling that we have today sometimes suggests that pronunciation should also be ‘standardised’. For example, there is only one standard spelling of butter today, but in the past these were also possible spellings: butere, buttere, boter, botere, botter, butre, buttur, butture, buttir, buttyr, botyr, boture, bottre and butyr.

(a) Does everyone pronounce the <r>? If it is pronounced, are there different ways of pronouncing the <r>?

(b) Almost everyone pronounces the <t>, but it can be done in various ways.

(c) Everyone pronounces the <u>, but it can be done in various ways.

Some accents have

received more attention than others from phoneticians and phonologists. These

are RP and GA.

Received Pronunciation (RP)

- ‘Received’ here is used in its older sense to mean ‘generally accepted’ – cf. the ‘received wisdom of the time’.

- other names: Queen’s English, BBC English, Oxford English, the Oxbridge accent, posh accent or la-di-da.

- in the UK, the RP accent has been associated with educated, southern English accent, and was thought of as the language of authority and power.

- reinforced by the BBC when it began broadcasting in the 1920s. However, since then, RP has been on the wane.

- According to one estimate, less than 3 per cent of British people speak RP in its pure form

- RP has lost a lot of its prestige in recent years, and regional accents are very common over the BBC, particularly over the home service (as opposed to the world service)

- RP speakers are being influenced by the Cockney accent (the local London, especially East London, accent) to form what is known as Estuary English (‘Estuary’ = the estuary of the River Thames) – some Cockney characteristics, eg the glottal stop in words like assortment and airport.

General American (GA)

- Not every American speaks GA, just as not every British person speaks RP

- GA is a ‘negative’ accent, defined as much by a lack of striking features that characterise some of the regional accents as by the presence of specific identifying features

- Other well-known American accents include: the Southern accent (with pin and pen pronounced alike, buy pronounced bah, no ‘r’ sound in car, etc.); the Black English accent (them pronounced dim, something pronounced somefin, buy pronounced bah, no ‘r’ sound in car, etc.); the New York accent and the Boston accent.