The Great Vowel

Shift

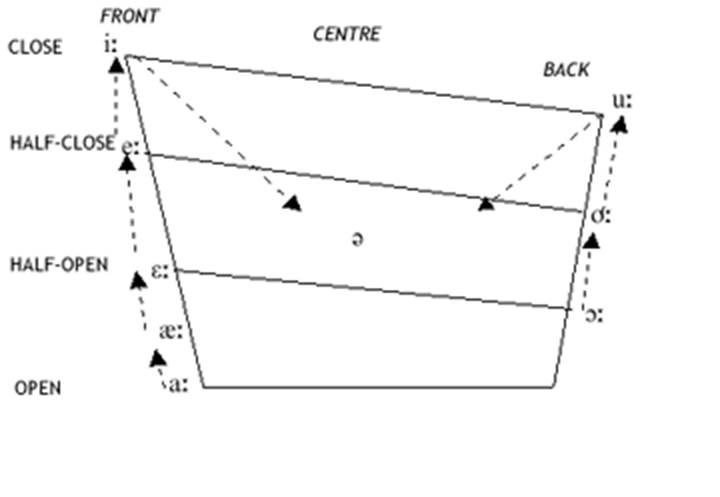

One major change in the pronunciation of English took place roughly between 1400 and 1700; these affected the ‘long’ vowels, and can be illustrated in the diagram below. This is known as the Great Vowel Shift (GVS). Generally, the long vowels became closer, and the original close vowels were diphthongised.

Here are some examples of words affected by the shift.

Word

|

ME

|

1400 |

1500 |

1600 |

1700

|

RP today

|

|

how, house |

uː |

ʊu |

əʊ |

əʊ,

aʊ |

aʊ |

aʊ |

|

food |

oː |

oː |

uː |

uː |

uː |

uː |

|

boat |

ɔː |

ɔː |

oː |

oː |

oː |

oʊ,

əʊ |

|

size |

iː |

ɪi |

əɪ |

əɪ,

aɪ |

aɪ |

aɪ |

|

green |

eː |

eː |

iː |

iː |

iː |

iː |

|

meat |

ɛː |

ɛː |

eː |

eː |

iː |

iː |

|

bake |

aː |

aː |

æː |

ɛː,

eː |

eː |

eɪ |

You might wonder how we can be confident about describing pronunciations in earlier centuries. Researchers have depended on what people have said about pronunciation; on the spelling ‘errors’ that were made; and on the rhymes used by poets of the time. In the 16th century, the first dictionaries, spelling books and grammars of English were produced. John Hart’s An Orthographie, first published in 1569, advocated a new spelling system, which he justified based on the various pronunciations of words.

The question that troubles people is why there was the GVS at all. The original ME vowels seem to be distinctive, and today’s vowels mean that words like sea and see are no longer distinguished in pronunciation.

Some linguists have described these ‘chain reactions’ as drag chains or push chains (the French linguist André Martinet coined the French terms chaîne de traction and chaîne de propulsion).

According to him, in a drag chain one sound moves from its original place, and leaves a gap which an exisitng sound rushes to fill, whose place is in turn filled by another, and so on. In a push chain, the reverse happens. One sound invades the territory of another, and the original owner moves away before the two sounds merge into one. The evicted sound in turn evicts another, and so on (Aitchison 1991: 154)

Leith suggests that there is also some social explanation for the change as different accented speakers met in London, the bourgeoisie were keen to distance themselves from the lower class and therefore consciously move towards closer vowel sounds.

One way [of creating distance] was to raise the vowel of mate even higher than that of the lower-class variant; and raising of the lowest vowel in the system would necessitate raising all the vowels above and, ultimately, pushing the vowel of tide into a diphthong. (Leith 1997: 145)

If you are interested in discussions about how did linguists know how people pronounced words in the past when there were no recording devices, you might like to look at Mazarin’s (2020) article. We basically relied on how people described pronunciation, some using special symbols, and some using spellings from other languages. We could also see how people rhymed words. Mazarin argues that there are four phases of development, shown in the two tables below. (Curly brackets enclose non-phonemic allophones that occur in some systems; round brackets indicate optional status.)

Front vowels

|

|

A 1500s |

B 1500s-1600s |

C 1600s-1700s |

D 1700s |

|

iː |

FLEECE |

FLEECE |

FLEECE |

FLEECE |

|

eː |

- |

MEAT |

(MEAT) |

FACE |

|

ɛː |

MEAT |

(WAIT) |

FACE |

{SQUARE} |

|

æː |

FACE |

FACE |

{START} |

START |

Back vowels

|

|

ME |

A |

B-D |

c 1900 |

|

uː |

MOUTH |

GOOSE |

GOOSE |

GOOSE |

|

oː |

GOOSE |

- |

GOAT |

/gout/ |

|

ɔː |

GOAT |

GOAT |

- |

TAUGHT |

|

ɑː ~ ɒː |

- |

{TAUGHT} |

TAUGHT |

START |