B. The rise of writing

Early writing started off as pictograms – pictorial representations, in the way that some modern road signs still do. The advantage of using pictograms as opposed to words is that the reader need not know a specific language to make sense of it, and the message can register quickly. (On the other hand, they might also be ambiguous.) I find it fascinating how road signs might differ from country to country: see below.

|

|

|

|

|

French cow |

British cow |

Spanish cow |

Portuguese cow |

|

|

|

|

|

Spanish schoolchildren |

British schoolchildren |

American schoolchildren |

|

|

|

|

|

Australian schoolchildren |

Singaporean schoolchildren |

South African schoolchildren |

The earliest

pictographic writing known to us was from Sumeria (in modern-day

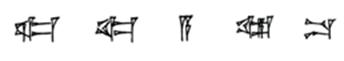

Here, we see Sumerian cuneiform syllabic symbols (cuneiform, meaning ‘wedge’ or ‘wedge shaped’ refers to the characters of the ancient inscriptions of Persia, Assyria, etc., composed of wedge-shaped or arrow-headed elements; and hence to the inscriptions or records themselves). At around the same time, Egyptian signs, known as hieroglyphics (‘sacred inscriptions’, Gk) also developed, and the symbols represented both sound and meaning.

![]()

Alphabetic writing began to emerge, and around 1000 BC, the Phoenicians devised an alphabet (above). This is the source of major alphabetic writing systems today including the Latin, Greek, Cyrillic, Hebrew and Arabic scripts. The spread could be related to the fact that they were traders and therefore travelled a lot.

![]()

The Greeks revolved or inverted the Phoenician letters (above) to produce Greek ones (below).

![]()

They largely retained the Phoenician names of the letters; whereas the Phoenicians had aleph, beth, gimel, daleth, etc., the Greeks had alpha, beta, gamma, delta, etc. Our modern word alphabet is derived from the names of the first two letters of the Greek alphabet.

![]()

The

Greeks occupied southern

Another

alphabet derived from the Greek alphabet is the Cyrillic alphabet (below), now

used for writing Russian and some other languages spoken in

![]()

Two alphabets derived from Phoenician (but not through Greek, unlike the Latin and Cyrillic alphabets) are the Arabic (first below) and Hebrew alphabets (second below).

![]()

![]()

Unlike the alphabets derived from the Greek one, the letters represent consonants (as opposed to vowel) sounds. Instead, vowels are indicated with diacritic dots. In addition, they are written right-to-left (as was the case in Phoenician) rather than left-to-right (in the alphabets derived from Greek). The Arabic writing spread largely because of its status as the language of the Koran (Qur’an) and of Islam. Muslims are strongly encouraged to recite the Koran in its original language Arabic; and this makes them different from Christians who are encouraged to read the Bible in their own languages (rather than in the original Hebrew and Greek).