C. Early English writing

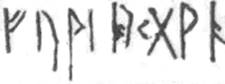

In

the very early days of English, what little writing there was was in the runic alphabet. The original runic alphabet

dates from at least the second or third century, and was formed by modifying the

letters of the Roman or Greek alphabet in an angular style so as to facilitate

cutting them upon wood or stone. Below is an example of an

inscription in the runic alphabet. (Runic marks are sometimes thought to have

magical and mysterious powers associated with them; the word rune means

‘secret’, and they were used mainly for inscriptions and charms!)

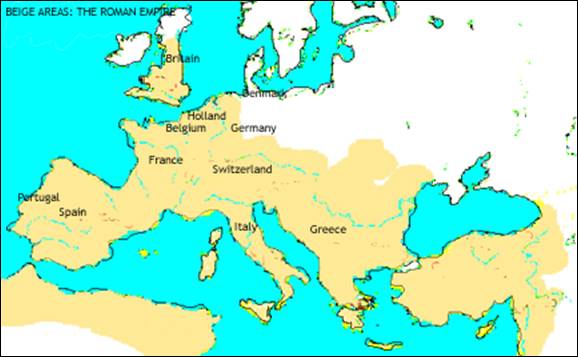

The

English language originated as the language spoken by a group of Germanic

tribespeople in northern

The Celts had actually invited some of the Germanic tribes to fight for them in some internal squabbles. This group is now collectively known as the Anglo-Saxons (and is made up of four tribes: Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians), and their language called Anglo-Saxon or Old English (OE).

The Germanic tribes had a runic system of writing, and whatever early

writing of OE there was at this time was with runes. However, remember that

writing was a very specialised skill and the vast majority of the Anglo-Saxon

had no need to read or write anything! The Anglo-Saxons were also probably

influenced by the Celts in

A problem arose: the Latin alphabet was developed to record Latin words and sounds. Some OE sounds were not used in Latin, so some additional letters (some adapted from the runes) were added. These include the following.

|

Letter (upper case, lower case) |

Name |

Sound represented (if you haven’t downloaded the Times Roman Phonetics font, you won’t see the correct symbols) |

|

<Ć>,

<ć> |

ash |

[ć]: this is the sound in the RP, Australian, American, etc. pronunciation of paddy; the letter <a> was reserved for the sound [a] or [ɑː]. ([a] is the sound in the Scottish pronunciation of paddy or the Malay pronunciation of padi; [ɑː] is the sound in the RP, American, etc. pronunciation of father.) |

|

<Đ>,

<đ> |

eth (or edh) |

[θ]and [đ] ([θ] is the sound in Arthur; and [đ] is the sound in other.) |

|

<Ţ>,

<ţ> |

thorn |

[θ] and [đ] – since the sounds represented by eth and thorn are the same, the symbols are theoretically interchangeable |

|

< |

wyn or wynn |

[w] as in wet |

|

< |

yogh |

[g] or [j] or [x] or [ ɣ] depending on where the letter is found. ([g] is the first sound in get, [j] is the first sound in yet; [x] and [ɣ] are not used in English today, but can be heard in the Scottish pronunciation of loch. |

Certain letters were, on the other hand, hardly ever used because there were already other letters available.

|

Letter |

Reason for lack of use in earlier OE |

|

<k> |

<c> was already available for the [k] sound; king was, for example, cyning in OE. |

|

<q> |

the [kw] sound was represented by <cw>; queen was, for example, cwene in OE. |

|

<v> |

<f> was used instead. The [f] and [v] sounds were allophonic; in other words, the [f] and [v] distinction was never used to distinguish words. Which sound you used depended on where the letter <f> occurred in the word. For example, knave was cnafa or cnafe in OE. Think also of the word of, which is often pronounced [əv] or [ɒv]. |

|

<z> |

<s> was used instead. The [s] and [z] sounds were allophonic; in other words, the [s] and [z] distinction was never used to distinguish words. Which sound you used depended on where the letter <s> occurred in the word. For example, size was syse or sise in OE. Today we still have some words where <s> (not in the beginning of a word) where the pronunciation is [z] like rise, houses, has, is. |

|

<g> |

< |

|

<j> |

this letter developed from the letter <i> much later. |

|

|

|

Detail from the Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle |

Look at an example of a piece of OE writing, taken from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written in the 9th century. (This contains a year-by-year entry of the events significant to the British. The following is the entry for AD 601 and tells of the conversion of the English to Christianity. Following common convention, I replace the letter yogh in the manuscript with <g>, so bear in mind it might represent a range of sounds; and I replace the wyn with <w>.)

Her

sende gregorius papa augustine arcebiscope pallium on brytene. 7

wel manega godcunde larewas him to fultume. 7 paulinus biscop gehwirfede eadwine norđhymbra cining to fulluhte.

This is a word-for-word rendering of the OE paragraph:

Here sent gregory pope augustine archbishop pallium in

This will not necessarily make sense to you because the words seem all jumbled up (we will explore why elsewhere). Here is a more idiomatically acceptable version for today:

In this year Pope Gregory sent the pallium to archbishop

Augustine in

(Note: a pallium is a woollen vestment conferred by the Pope upon

archbishops.)

As would be expected of

languages that have recently adopted an alphabet, the OE system was closely

phonological – more so than today. Because it was phonetic, the way a word is

spelt depends on the way the writer pronounces the word. If we remember that there

were diverse accents and dialects then (and these accent and dialect

differences are still with us today), it would not be surprising that the same

word might be spelt differently in different parts of the country.

In the later part of the

OE period though, the spelling based on one dialect (the West-Saxon or

Move on to Section D to

find out how the English spelling system became more complex.