Middle English and Modern English

Phase 4. The Norman Conquest (1066 onwards)

Meanwhile,

there were also Scandinavians who settled in northern

Meanwhile,

there were also Scandinavians who settled in northern

There

was already a certain amount of contact between the Normans and the English at

the turn of the millennium. It was through the contact between the English king

Edward that the duke of

There

was already a certain amount of contact between the Normans and the English at

the turn of the millennium. It was through the contact between the English king

Edward that the duke of

(There are lots of websites on 1066; just do a quick web search. Try this one if youve got a broadband connection because there are lots of images: http://battle1066.com/.)

William brought

along with him his followers, and key positions in the government and in the

church were taken over by

|

|

Had prestige? |

Written or spoken? |

Used by whom? |

|

French |

Yes |

Both |

|

|

Latin |

Yes |

Mainly

written |

Mainly

educated |

|

English |

No |

Spoken |

English-

& Norsemen |

|

Celtic |

No |

Spoken |

Celts |

Clearly, this situation was a

potentially unstable one. The

The position of the English and the Scandinavians as conquered people helped the process of fusion between them, described above, so that the English language continued to change under these circumstances. Doubtless, some English speakers learnt French (the centripetal force) to gain the advantages from aristocracy; and some Normans perhaps officials sent to far outposts learnt English through their contact with local communities (accommodation perhaps?) Later on, after some 150 years, the enmity and distinction between the English and the Normans became less pronounced, and intermarriages became common.

From the 13th

century, there was a change in the political climate. King John of

Compare the following accounts of children learning languages in Medieval Britain. This was how the relationship between English and French was expressed by Robert of Gloucester (in his Chronicle, written about 1300 the translation is on the right, but you should be able to make out quite a bit of his English already).

|

țus com

lo engelond. in to normandies

& țe

& speke french as hii dude at om. & hor children dude also teche. so țat heiemen of țis lond. țat of hor blod come. holdeț alle țulk speche. țat hii of hom nome. vor bote a man conne frenss. me telț of him lute. ac lowe

men holdeț to engliss. & to hor owe speche ich wene țer ne beț in al țe world. contreyes none. țat ne holdeț to hor owe speche. bote engelond one. ac wel me wot uor to conne. boțe wel it is. vor țe more țat a mon can. țe more wurțe he is. |

Thus came lo! England into

Normans hands, And the And spoke French as they did at

home, and their children did also teach, So that high men of this land

that of their blood come Hold to all that speech that

they took of them; For unless a man knows French,

men think little of him. But low men hold to English and

to their own speech yet. I suppose there be none in all

the countries of the world That do not hold to their own

speech, save for But yet it is well for a man to

know both, For the more a man knows the more he is worth. |

Later, Ranulph Higden expressed similar views (he wrote in Polychronicon in Latin, and this is John Trevisas translation in the 1380s the modern version is on the right):

|

This apeyring

of țe burț tonge ys bycause

of twey ținges on ys for chyldern in scole a Also

gentil men children buț ytau |

The impairing of the native

tongue is because of two things one is that children in school, against the

usage and custom of other nations, are compelled to drop their own language

and to construe their lessons and their tasks in French, and have done so

since the Normans first came to England. Also, gentlemens children are taught to speak French from the time that they are rocked in their cradles and can talk and play with a childs brooch; and country men want to liken themselves to gentlemen, and try with great effort to speak French, so as to be more thought of. |

However, Trevisa, now referring to the 1380s appends the following comment:

|

țys manere was moche y-used tofore țe furste moreyn

and ys sethe somdel y-chaunged

now, țe Also

gentil men habbeț now moche yleft for to teche here childern frensch. Hyt semeț a gret wondur hou |

This

fashion was much followed before the first plague [1348] and is since

somewhat changed

Now, the year of our Lord one thousand, three hundred,

four score and five, in all the grammar schools of England, children leave

French, and construe and learn in English. Also gentlemen have now to a great extent stopped

teaching their children French. It seems a great wonder how English, that is

the native tongue of Englishmen and their own language and tongue, is so

diverse in pronunciation in this island, and the language of Normandy is a

newcomer from another land and has one pronunciation among all men that speak

it correctly in England. |

The

antagonism between the English and the French grew, leading to the Hundred

Years War (13371453). National feeling was against the French and things

associated with the French including the French language (the centrifugal

force?). In 1362, English was used for the first time at the opening of

Parliament. Literary expression also began to made in

English, and not only in Latin and French led by Chaucer

(c. 13431400). By about 1425, English was widely used in

The

antagonism between the English and the French grew, leading to the Hundred

Years War (13371453). National feeling was against the French and things

associated with the French including the French language (the centrifugal

force?). In 1362, English was used for the first time at the opening of

Parliament. Literary expression also began to made in

English, and not only in Latin and French led by Chaucer

(c. 13431400). By about 1425, English was widely used in

The Norman period brought about new spelling conventions (scip became ship; boc became booc), but most importantly, some 10,000 French words came to be borrowed. Notice that the peak of the borrowing came at around 1375, when French was on its way out.

The Norman Conquest plays a crucial role in the tradition OE-ME-MnE distinction, where ME is the period when the French influence was the greatest. Others, however, emphasise the morphological basis of the OE-ME-MnE distinction, as in:

|

The traditional basis of the divisions between Old and Middle English and between Middle and Modern English has been morphological: as Sweet put it in the 1870s, Old English is the period of full inflexions (nama, giefan, caru), Middle English is the period of levelled inflexions (naame, given, caare) and Modern English of lost inflexions (naam, giv, caar). (Bourcier 1981: 122) |

We have elsewhere discussed the evolution of English from being a synthetic language to a more analytic language. What then are the reasons for this?

(a) Bourciers quotation suggests that this might be phonological in nature. The English language has a very strong tendency to emphasise the distinction between stressed and unstressed syllables, resulting in unstressed syllables having their vowel sound reduced to a neutral schwa /@/ or to /I/. Inflexions are generally not stressed, and given that English almost ceased to be written altogether in the early ME period, English had become only a spoken language. The different inflexions could not be heard anymore through the generalised use of the neutral vowel (levelled inflexions meaning that all case inflexions began to sound more or less alike). This resulted in the inflexions being unable to make the traditional OE case distinctions, so that these distinctions had to be made by other means the use of prepositions and the reliance of word order.

(b) The other reason given is the

language-contact situation between English and Norse speakers. They lived side

by side and intermarried and forgot their enmity when they were subjugated by

the

(c) The fact the English in the period was only a spoken language, with no written standard to provide a centripetal force, meant that there would be less opposition to change; there was hardly anything to hold back innovation. The fact that English was a low-prestige language at this time also meant that there was hardly any concern about correctness.

Phase 5. The Reformation, the Renaissance, the rise

of science, and the establishment of colonies (1500 onwards)

This period saw the beginning of a new way of doing things and a break from the feudalistic, Medieval past.

The English Reformation has to do with Henry VIIIs breaking away from the (Roman) Catholic church. The Medieval world view saw the European nations as being part of Christendom under the authority of the Pope, with Latin as a unifying language. This was to change. This saw the rise of the notion of nationhood and nationalism - and therefore of national languages. Some saw the development of an English language capable to cope with all kinds of situations as being necessary for nationhood. The English language therefore took over Latin as the language of learning. The notion of a standard language also began to gain importance. (The notion of a standard language will be discussed a couple of weeks from now.)

The Renaissance has to do with a renewed interest in the Classics (essentially Latin and Greek Classics). Many thought that in order for the English language to be capable of dealing with the new way of doing things in science, English had to borrow from Latin both the lexis as well as the structure (hypotaxis). This is linked to the notion of standardisation mentioned above, in that one way of achieving a language that is capable of coping with the new circumstances is to adapt it towards other languages (in this case, Latin), that has served as standard languages.

We can re-use the table to summarise the language situation in the early MnE period.

|

|

Had prestige? |

Written or spoken? |

Used by whom and when? |

|

French |

Yes |

Both |

Very

few; occasionally |

|

Latin |

Yes |

Mainly

written |

Highly

educated men (not women); learned texts, in university |

|

English |

Yes |

Both |

The general populace, high and low with much variation; for almost every occasion |

|

Celtic |

No |

Spoken |

Celts |

We will also explore one interesting aspect of English use during this period: the use of thou and you (click for link).

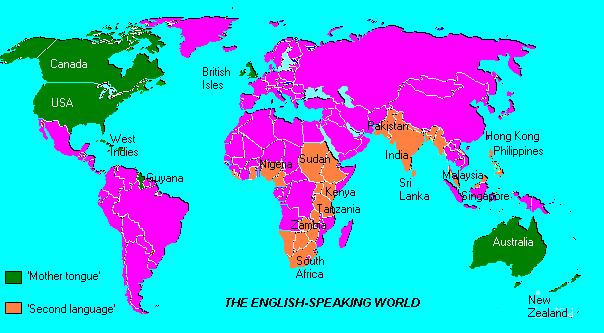

The new spirit of enquiry that gave rise to science and the notion of empiricism is probably also related to the spirit of exploration. The British also began to establish colonies abroad, and by so doing, took the English language out of the continent of Europe. This is related to the new strategy of mercantilism (the theory that a nations interests are served of overseas trade and restriction of imports), as opposed to the more subsistent economy in the past to fuel this, raw materials from elsewhere were required. The result is that there are speakers of English in every continent today. In 1600, around the time of Shakespeare, there were about 6 million speakers of English. Today, it is used by at least 750 million people, if not more. If you look at the time chart, you will notice that the events to do with the history of English take place not only in Europe, but in other parts of the world. It is not possible to do justice to a description of all places where English is spoken, so this module has chosen to focus on some of the developments in North America and in South-east Asia, particularly Singapore.

The transportation of English to new areas led to new kinds of language contact. In America, the contact was often with the languages of the other European immigrants rather than with the native American Indians. In other places, the contact was with the existing languages.

We can make a distinction between immigration (settlement) and (exploitation) colonisation, because in the case of immigration (North America, Australia, New Zealand, etc.), the Anglo-Saxon culture of the original speakers have also been brought over. In the case of colonisation (Jamaica, Nigeria, Zambia, India, Malaysia, etc.), English is transported to a new socio-cultural situation.

The external history of the

language adds a further dimension to our consideration of English, and throws

up certain patterns of change in the language.

Summary

- The history of a language has to do with language shift: people choosing to use this language over another language (English over a Celtic language, English over Latin, English over Norse, English over French, English over Malayalam). It is ultimately people who decide what language to use and how to use it. Language does not have a life of its own, although we might sometimes talk as if it did.

- It has also got to do with language change: people willing to adapt, consciously or unconsciously, the language that they use to suit their own purposes (have the inflexions become redundant? have they got enough words to express their Christian faith, their interest in the arts, their interest in learning, their encounter with unfamiliar flora and fauna?) Discussions about the right or the correct language are not very meaningful out of the context of people needing to accomplish things through language.

- We notice the themes of language contact (OE and ON, English and French, English and Malay/Hokkien); of prestige languages/dialects (English or Celtic? English or Norse? English or French? English or Latin?). More than any other language, English is a result of language contact. Some might less flatteringly refer to the English language as a creole or a bastard language. Indeed, some claim that it is the adaptable and welcoming nature of the English language towards other languages that it comes into contact with that makes it eminently suited for its role as a world language.

- A lot of people are worried about the notion of change in language. If we use English as our example, change in language is almost inevitable if it is to remain dynamic and relevant to the speakers of the language. Quite often, there are internal checks and balances to ensure change will be at a manageable rate.

Note: if you are fascinated by British history, you can explore this site for British schools and school teachers: http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/index.htm

When youre ready to take the quiz based on this topic, go to the IVLE page and click on Assessment on the left, and then on Middle and Early Modern English period.

© P. Tan 2018