EL1102

Studying English in Context

Lecture No. 8 (Part 1)

I will use a video to convey most

of the information; the notes are for you to read and digest. You can view the

video through the NUS intranet: click on

http://ivle.nus.edu.sg/ivle/search/template.asp?courseid=EL1102

Click on ‘videos’ on the left. You

will be asked for your user ID and password. (Your user ID must be in the form

NUSSTU/xxxxxs for students or NUSSTF/xxxxxx for staff.) Then click on ‘The

Mother Tongue’, and you should be off.

If your computer hasn't got a

player installed, you can go through the following steps:

- Click here to download

SGI DirectShow Player for Win95/98/NT

- During

the download, you will be prompted to enter a location for saving the

setup file. Save it in \Windows\Temp. This temporary file will not

be required after the player is installed.

- Using

the Windows Explorer or Command Prompt, change to directory \Windows\Temp

- From

the Windows Explorer or Command Prompt, run the DirectShow player set-up

program dssetup to install the DirectShow player. Click on all the next

buttons.

A table is distributed with this lecture, dealing with the peoples discussed in

this lecture: http://courses.nus.edu.sg/course/elltankw/EL1102-wk8c.htm

Go to the time chart: http://courses.nus.edu.sg/course/elltankw/EL1102-wk8a.htm

There are lots of Web pages with information on

the external history. Here are some useful links: http://courses.nus.edu.sg/course/elltankw/EL1102-wk8b.htm

At this point now, we are ready to discuss some aspects of the external history

of English and we can relate some of it to the internal history. Please consult

the time

chart. Because we will discuss the external history, I will give a

quick sketch of the salient events through a series of maps. Our main interest

will be in the relationship between the external history and the

language.

Phase 1. Pre-English Days

(AD 1–450)

Notice that there was no such thing as ‘English’

during this period. The inhabitants of Britain — the Britons — did not speak

English, but various Celtic languages. We mentioned in the last lecture

that modern Welsh, Irish Gaelic and Scots Gaelic are Celtic languages and

‘survivors’ of the original languages in Britain. In Northern France, a Celtic

language that remains to be spoken is Breton. Some of you might be aware of

Celtic legends (eg King Arthur and the knights of the round table) or of

the Asterix comics set in the Roman period.

This was also the time when

the Roman Empire was dominant, and continued expanding until the second

century. For much of this period, Britain was a Roman colony. The language of

the Roman Empire was Latin. Some form of Latin would have been spoken by

at least part of the local population in Britain and other Roman colonies.

However, the dominant languages continued to be the Celtic languages. This is

unlike Gaul (‘France’), another Roman province, where Latin to a large extent

replaced the local Celtic languages. (Modern French is derived from the variety

of Latin spoken in Gaul.)

This was also the time when

the Roman Empire was dominant, and continued expanding until the second

century. For much of this period, Britain was a Roman colony. The language of

the Roman Empire was Latin. Some form of Latin would have been spoken by

at least part of the local population in Britain and other Roman colonies.

However, the dominant languages continued to be the Celtic languages. This is

unlike Gaul (‘France’), another Roman province, where Latin to a large extent

replaced the local Celtic languages. (Modern French is derived from the variety

of Latin spoken in Gaul.)

(Please note that during

this period, it is meaningless to talk about ‘England’. There was no such

entity then. We can only refer to the whole island — Britain.)

Phase 2. Anglo-Saxon

invasions and consolidation in Britain (449 onwards)

The OE extract from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

tells us that the Romans faced many problems from attacks by various tribes,

including the Huns. In 410, the last of the Roman legions left Britain, which

meant that the island was left open for attack or occupation by various tribes.

From about 449, these so-called Germanic tribes started attacking and

migrating to Britain. They were originally from around present-day Germany,

Denmark and the Netherlands (Holland). The original Celtic tribes were chased

off to the northern, western and south-western extremities, and it is therefore

not surprising that it is in these places where some Celtic languages (Welsh,

Scots Gaelic) survive. Those who remained in the central areas would probably

have been overwhelmed by the Germanic tribes, and have merged in with them, and

we can perhaps think of this as the centripetal force at work. It is

interesting that there are in fact very few Celtic borrowings into the English

language.

The tribes that set up

their kingdoms in Britain are collectively known as the Anglo-Saxons.

Bede, an 8th century historian, tells us these tribes included the Jutes

and Angles (both from present-day Denmark), and Saxons (northern

Germany and the Netherlands). A fourth tribe, the Frisians (from

present-day Netherlands), also came to Britain. Their language existed in

several dialects — generally each tribe (Angle, Saxon, Jute, Frisian) had its

own associated dialect. Their language is often collectively known as Anglo-Saxon

or Old English. Sometimes the term Saxon is used on its own

because the ‘standard’ that developed was based on the West Saxon (or Wessex)

dialect in south-west England.

Latin texts of the time

used the terms Angli and Anglia to describe the country, and

local writers describe their language as Englisc (English). These terms

derive from the name of the Angle tribe (in OE Engle). The people and

the land, collectively, were known as Angel cynn (‘Angle-kin’), and it

was not until around 1000 that the name Englaland (Angles’ land) was

used.

By and large, they were

well-known for their military prowess, and not for their sophisticated culture.

They were concerned with ordinary day-to-day living, and there was a lot of

in-fighting until they were united by King Alfred the Great (871–899). As a

result of this a standard began to be developed based on the Wessex (‘West

Saxon’) dialect. Writing was very, very limited (first text: around AD 700),

and generally, only specially trained scribes (usually monks) could write.

Writing was only used for special records. Therefore, whatever writing there

was tended to have the feel of conversation — we referred to the paratactic

structures in our discussion of the OE passage. Additionally, we can consider

the down-to-earth vocabulary as reflecting the comparatively unsophisticated

nature of the Anglo-Saxons.

Phase 3. Viking invasions

(787 onwards)

The Scandinavian attacks on

Britain took place between 787 and 850. These people were commonly known as the

Vikings and they were Germanic inhabitants in presently Denmark, Norway and

Sweden. What is interesting therefore is that they were originally also

neighbours of the Anglo-Saxons, and therefore spoke a closely related language

(Old Norse) that they would have understood a lot of. We can call Old

Norse and Old English cognate or related languages.

The Scandinavian attacks on

Britain took place between 787 and 850. These people were commonly known as the

Vikings and they were Germanic inhabitants in presently Denmark, Norway and

Sweden. What is interesting therefore is that they were originally also

neighbours of the Anglo-Saxons, and therefore spoke a closely related language

(Old Norse) that they would have understood a lot of. We can call Old

Norse and Old English cognate or related languages.

The Scandinavians raided

towns and monasteries; they captured towns and cities and then proceeded to

settle in these places. The army of Alfred the Great resisted them for seven

years before taking refuge in the marshes of Somerset. However, fresh troops

enabled him to attack the Scandinavians, under Guthrum, and defeat them

convincingly. Alfred and Guthrum signed the Treaty of Wedmore in 878, and the

Scandinavians (‘Danes’) agreed to settle on the east of the line, running

roughly from Chester to London. This region would be subject to Danish law, and

is therefore known as the Danelaw. The Danes also agreed to become

Christians and Guthrum was baptised. This began the process of the fusion of

these two peoples, coming to a head in the next period of history.

This, however, was not the

end of the battles. There were more Scandinavian attacks later on, and in the

new millennium, England was ruled by Canute (or Cnut), the Danish king.

After taking over the land,

the Scandinavians often lived peaceably with the English, and there were many

intermarriages. They adopted English customs, and the English accepted them.

More important for our purposes, however, is the language contact situation

resulting in the English language accepting Old Norse (ON) words and forms. For

example, the personal pronouns they, them and their come from ON.

So does the 3rd person inflexion for verbs –s. Words that are borrowed

from ON include anger, cake, egg, loan, root, skirt, steak, take and window.

There was no obvious centripetal or centrifugal force at work.

Many suggest that the contact

between OE and ON might have led to the loss of many inflexions. Because the

inflexions were different in OE and ON, they were often unhelpful in

conversation between OE and ON speakers. They suggest that speakers might have

deliberately not used the inflexions to facilitate communication. In situations

of intermarriage, the children might grow up learning this ‘simplified’ version

of English. Some would even say that the English language had undergone a

process of pidginisation and creolisation.

Phase 4. The Norman

Conquest (1066 onwards)

Meanwhile, there were also

Scandinavians who settled in northern France, and they came to an agreement

with the king of France. They acknowledged the French king, but they had a duke

from among their people in this region, called Normandy. They would,

from then on, be known as Normans. (The adjective is Norman, as

in ‘Norman army’.) Like the Scandinavians in Britain, the Normans were also

highly adaptable, and very quickly adopted French culture and civilisation,

and, it would appear, willingly gave up their native language and spoke French

as their mother tongue, although their dialect, Norman French, was

distinct from Parisian (Central) French.

There was already a certain

amount of contact between the Normans and the English at the turn of the

millennium. It was through the contact between the English king Edward that the

duke of Normandy, William, believed that he was to succeed the English throne.

When Edward died, an English earl, Harold, was elected king instead. Furious as

this decision, William sailed across to an unprepared English army. After

Harold was killed in battle, the English army became disorganised and soon

retreated. On Christmas day in 1066, William (‘the Conqueror’) was crowned

king.

There was already a certain

amount of contact between the Normans and the English at the turn of the

millennium. It was through the contact between the English king Edward that the

duke of Normandy, William, believed that he was to succeed the English throne.

When Edward died, an English earl, Harold, was elected king instead. Furious as

this decision, William sailed across to an unprepared English army. After

Harold was killed in battle, the English army became disorganised and soon

retreated. On Christmas day in 1066, William (‘the Conqueror’) was crowned

king.

William brought along with

him his followers, and key positions in the government and in the church were

taken over by Normans. The original English lords had either been killed in

battle or been executed as traitors. The Normans continued to speak French in England,

and therefore, almost overnight, English was relegated to the status of a

‘peasant language’. For several generations after the conquest, all the

important positions were taken by Normans, or foreign men. As they had

continued contact with France, the nobility continued to speak French, and did

not bother to learn English.

The position of the English

and the Scandinavians as conquered people helped the process of fusion

between them, described above, so that the English language continued to change

under these circumstances. Doubtless, some English speakers learnt French (the centripetal

force) to gain the advantages from aristocracy; and some Normans – perhaps

officials sent to far outposts – learnt English through their contact with

local communities (accommodation perhaps?) Later on, after some 150

years, the enmity and distinction between the English and the Normans became

less pronounced, and intermarriages became common.

From the 13th century,

there was a change in the political climate. King John of England fell out with

King Philip of France. Philip demanded that John should appear in Paris to

answer some charges against him. John replied that as king of England, he was

not subject to the jurisdiction of the French court. Philip, however, replied

that as duke of Normandy, he was. John therefore demanded safe conduct to

Paris, but Philip gave out terms that he could not accept. The result was that

John did not appear on the day of the trial. Philip promptly invaded Normandy

and in 1204, Rouen surrendered, and the English lost Normandy. Subsequently,

any Norman lords in England had their lands in France confiscated by the French

king. The Normans now had to choose between their French estates and their

English estates. Those who remained in Britain, therefore, began to lose their

continental connexions and began to identify themselves with England. As a

result of this, the use of English began to spread, even among the upper

classes.

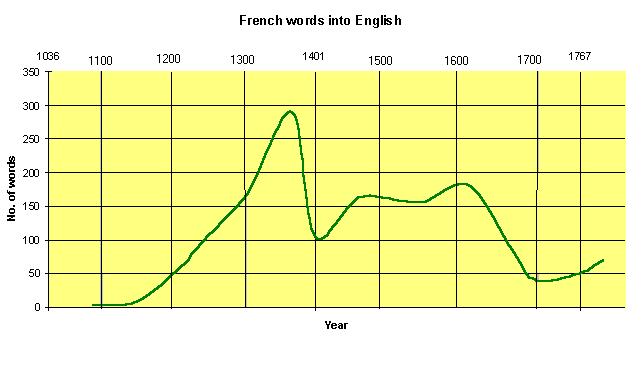

The Norman period brought

about new spelling conventions (scip became ship; boc

became booc), but most importantly, some 10,000 French words came to be

borrowed. Notice that the peak of the borrowing came at around 1375, when

French was on its way out.

Phase 5. The Reformation,

the Renaissance, the rise of science, and the establishment of colonies (1500

onwards)

The English Reformation has to do with Henry

VIII’s breaking away from the (Roman) Catholic church. This saw the rise of the

notion of nationhood and nationalism. Some saw the development

of an English language capable to cope with all kinds of situations as being

necessary for nationhood. The English language therefore took over Latin as the

language of learning. The notion of a standard language also began to

gain importance. (The notion of a standard language will be discussed in a

later lecture.)

The Renaissance has to do

with a renewed interest in the Classics (essentially Latin and Greek Classics).

Many thought that in order for the English language to be capable of dealing

with the new way of doing things in science, English had to borrow from Latin –

both the lexis as well as the structure (hypotaxis). This is linked to the

notion of standardisation mentioned above, in that one way of achieving

a language that is capable of coping with the new circumstances is to adapt it

towards other languages (in this case, Latin), that has served as standard

languages.

The British also began to

establish colonies abroad, and by so doing, took the English language out of

the continent of Europe. The result is that there are speakers of English in

every continent today. In 1600, around the time of Shakespeare, there were

about 6 million speakers of English. Today, it is used by at least 750 million

people, if not more. If you look at the time chart, you will notice that the

events to do with the history of English take place not only in Europe, but in

other parts of the world. It is not possible to do justice to a description of

all places where English is spoken, so this module has chosen to focus on some of

the developments in North America and in South-east Asia, particularly

Singapore.

The transportation of

English to new areas led to new kinds of language contact. In America, the

contact was often with the languages of the other European immigrants

rather than with the native American Indians. In other places, the contact was

with the existing languages.

We can make a distinction

between immigration (settlement) and colonisation, because in the

case of immigration (North America, Australia, New Zealand, etc.), the

Anglo-Saxon culture of the original speakers have also been brought over. In

the case of colonisation (Jamaica, Nigeria, Zambia, India, Malaysia, etc.),

English is transported to a new socio-cultural situation.

The external history of the language adds a

further dimension to our consideration of English, and throws up certain

patterns of change in the language.

- The

history of a language has to do with people choosing to use this

language over another language (English over a Celtic language,

English over Latin, English over Norse, English over French, English over

Malayalam). It is ultimately people who decide what language to use

and how to use it. Language does not have a life of its own, although we

might sometimes talk as if it did.

- It

has also got to do with people willing to adapt, consciously or

unconsciously, the language that they use to suit their own purposes (have

the inflexions become redundant? have they got enough words to express

their Christian faith, their interest in the arts, their interest in

learning, their encounter with unfamiliar flora and fauna?) Discussions

about the right or the correct language are not very meaningful out of the

context of people needing to accomplish things through language.

- We

notice the themes of language contact (OE and ON, English and

French, English and Malay/Hokkien); of prestige languages/dialects

(English or Celtic? English or Norse? English or French? English or

Latin?). More than any other language, English is a result of language

contact. Some might less flatteringly refer to the English language as

a creole or a bastard language. Indeed, some claim that it

is the adaptable and welcoming nature of the English language towards

other languages that it comes into contact with that makes it eminently

suited for its role as a world language.

- A

lot of people are worried about the notion of change in language.

If we use English as our example, change in language is almost inevitable

if it is to remain dynamic and relevant to the speakers of the language.

Quite often, there are internal checks and balances to ensure change will

be in a manageable rate.

Click

here to go to Part 2 of Lecture 8

Click here to

return to the EL1102 Home Page.

Click here to

go back to the EL1102 lecture schedule.

Click here to

go to Tutorial No. 6, based on this topic.

Email

me for comments or questions.

© 2001 Peter Tan